Good Land Does Not Lie Fallow? Is Depopulation a Threat for Ukraine?

If war is a national tragedy, then the demographic crisis raging in Ukraine is a national catastrophe. It is the slow death of a nation, its impact comparable to that of a large-scale epidemic, but more insidious and drawn out.

The process unfolding in Ukraine can be described as Xeraino (from the Greek xeros—“dry”), or a “drying out.” The nation’s life potential is “wilting,” accelerated both by the exhaustion of the country in the midst of full-scale war and by the toxic policies of domestic elites over decades that have led Ukraine to this disaster.

In 1991, Ukraine’s population reached 52 million. Today, by various estimates, it has shrunk to 28 million—a decline of 46 percent.

Of course, this stems from a mix of objective and subjective factors.

Among the objective ones is the peculiar nature of the third demographic transition—the simultaneous decline in fertility and rise in life expectancy.

All European countries are now experiencing this transition, marked by an aging population and fertility rates below 2.2 (the number of births per woman of childbearing age). A rate of 2.2 is the minimum for stable population replacement. Across Europe, fertility rates are steadily approaching 1—an unmistakable sign of depopulation.

Fertility decline also has civilizational roots: the gradual abandonment of the patriarchal family model (especially in developed countries) and the emancipation of women, who increasingly prioritize self-fulfillment over childbearing.

Yet while all high-fertility countries (mostly in Asia and Africa) resemble each other, every low-fertility country experiences crisis in its own way.

Take South Korea and Ukraine. Both have fertility rates around 0.7–0.8. But in Korea, this reflects rapid development, workaholism and emotional burnout, while in Ukraine it is the result of economic collapse and war, eroding any positive scenario of the future.

In 2024, Ukraine recorded 495,000 deaths—2.8 times more than the 176,600 births.

Compared with 2023, births fell by 5.7 percent, while deaths decreased by just 0.2 percent.

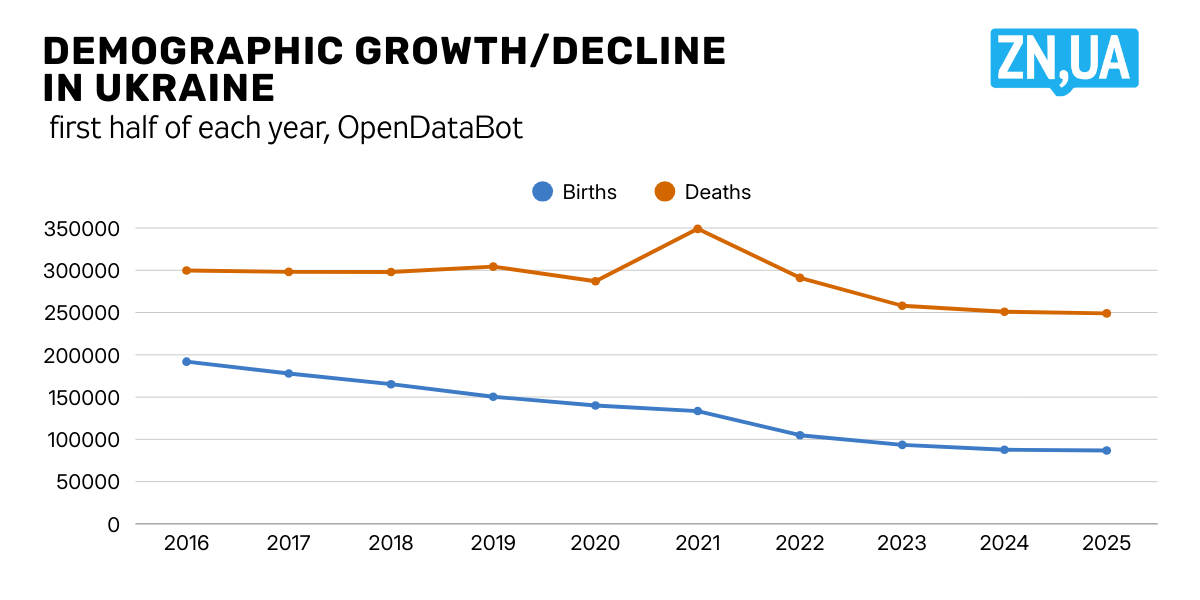

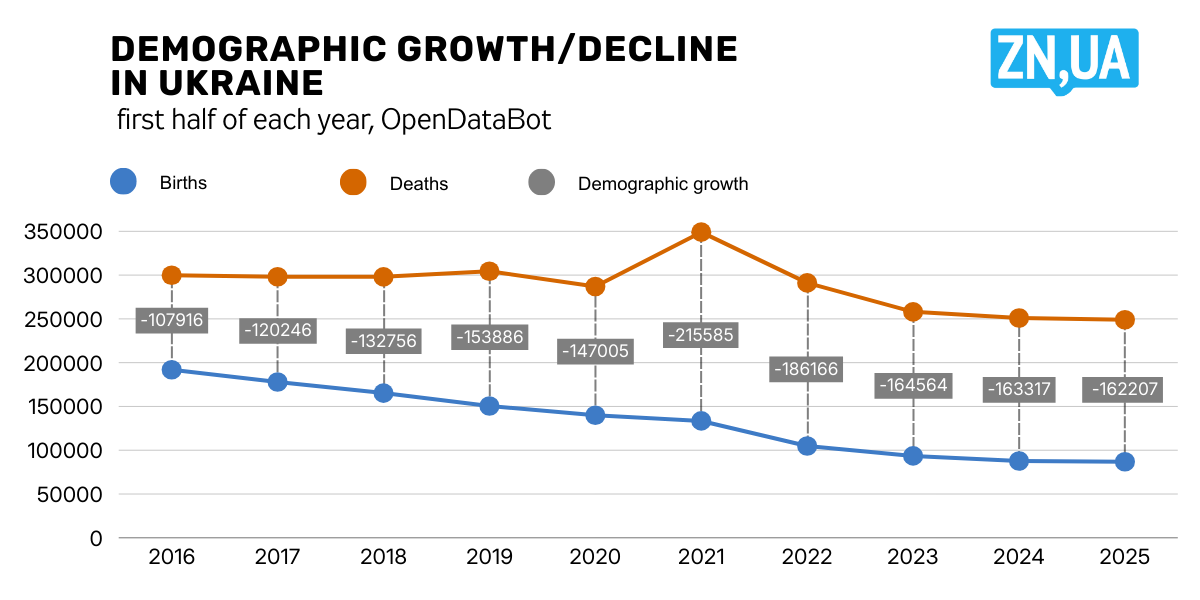

According to OpenDataBot, in the first half of 2025 there were 86,795 newborns and 249,002 deaths (see table). As the data note, “Currently, there are three deaths for every newborn—and this ratio has held steady for the past five years... In ten years, the birth rate has fallen 2.2 times. While in 2016 an average of 32,000 babies were born per month, this year it is only 14,000.”

Annualized, negative demographic growth has worsened from 107–130,000 per year in 2016 to around 320,000 today, driven by both lower fertility and rising mortality.

Ukraine’s third demographic transition has its own specifics: fertility is falling as in Europe, but mortality is edging toward levels typical of Africa and Asia, due mainly to men’s shorter life expectancy.

These trends had taken root even before the full-scale invasion. Stripping out wartime effects, excess mortality would still be around 45–50,000 per year.

Subjective factors also play a role. The EU population, despite low fertility, is growing thanks to migration, including Ukrainian refugees.

Ukraine, by contrast, faced an outflow even before the war in the form of labor migration (with almost no immigration in return). Since 2022, this has been multiplied many times over by refugees.

Today, Ukraine’s total population decline is about 900,000 people per year: 320,000 from deaths outpacing births, 500–550,000 from refugees leaving.

Some experts still expect a post-war baby boom, arguing that despite the Holodomor, repression and wars, the nation has always rebounded.

Others ask: does Ukraine even need a large population? Malthusian theory suggests that “the fewer the people, the better”—in other words, resource rents are shared among fewer inhabitants.

This is a fallacy.

Currently, Ukraine is buoyed by the “demographic hump” of the Soviet era: Ukrainians aged 30–34, the largest cohort at 3.5 million. In 25–30 years, they will become pensioners.

The smallest cohort is children aged 0–4—just 1.5 million—who should sustain the demographic pyramid for the next 50 years.

In other words, even if women of childbearing age return from Europe, it would only soften the catastrophe, not reverse the trend.

The state can ease the crisis by shaping incentives for population growth and by determining whether Ukraine’s demographic base can sustain dynamic economic development.

Economists refer to Okun’s Law, which links GDP growth with unemployment. One interpretation of it reads as follows: each additional 1 percent in unemployment cuts GDP growth by 3 percent. The reverse works differently: a 1 percent rise in GDP reduces unemployment by just 0.25 percent after three quarters.

One might ask how it looks when applied to Ukraine. In the event of a dynamic post-war economic recovery, Ukraine will need people in the form of labor.

If GDP were to rise by 30 percent over five years, unemployment would fall by 12 percent. But with the reserve of economically active population capped at 10 percent, Ukraine is already “in the red”—a deficit that will only worsen.

In theory, migrant labor from the world’s poorest countries could help.

Based on International Labor Organization data, Ukraine could attract workers only from countries where per-capita labor income is under $200/month—such as Cambodia, Syria or several African countries (Mozambique, Congo, Chad).

But could Africans become Ukraine’s chemists, metallurgists and rocket engineers? The problem is not discrimination, but reality: African nations are pursuing industrial policies to absorb their own labor, and their excess workforce usually migrates to the EU or US for service jobs or to rich countries for social benefits.

Thus, the demographic crisis is also a crisis of post-war recovery.

Besides, most modern growth models rely on domestic demand—i.e., human capital. Industrialization is only feasible in countries with at least 20 million people, since it depends partly on the domestic market.

The social factor is also consequential. Post-war, Ukraine’s population will be about 25 million, including 10 million pensioners, 5 million children and up to 3 million disabled people and veterans. That leaves only 7 million economically active people supporting 18 million dependents. Roughly: for every two workers, there will be one child, one or two pensioners, and for every two working families, one welfare recipient. So without an influx of around 5 million economically active people, Ukraine faces economic and social collapse.

But what about the experience of countries such as Australia or Mongolia, with vast territories and relatively small populations?

In Australia, 40 percent of territory is unfit for habitation and 80 percent of people is concentrated within a 40-km-wide coastal strip, mainly in the southeast; the vast interior is virtually uninhabited. Thus, with a population of 27 million, Australia has roughly the same area of land suitable for crop cultivation as Ukraine, while at the same time possessing far larger mineral reserves.

For example, before the war Ukraine mined 40 million tons of iron ore, whereas Australia mined 950 million tons. The country is also among the largest exporters of natural gas. No one threatens Australia; it has fully resolved its national security issues and does not require post-war economic recovery.

Exports of natural resources from Australia amount to up to $200 billion (coal, iron ore, gold, alumina) and, when agricultural products are included (chiefly pasture-based livestock), exceed $300 billion.

For comparison, Ukraine’s total pre-war exports were $68 billion (the 2021 peak).

In other words, Australia’s resource-rent factor is almost 5–6 times higher than Ukraine’s, especially given the contraction of our export potential during the war.

Accordingly, the Malthusian model works in Australia thanks to its vast natural resources and low defense costs, whereas it does not in Ukraine.

The example of Mongolia is altogether irrelevant. Like Australia, it does not spend money on defense (owing to declared neutrality), but unlike Australia it remains a middle- and low-income economy; that is, its example is not particularly positive for active emulation.

Israel provides a more fitting analogy.

In 1973, during the Yom Kippur War and after the war of attrition, Israel had 3.3 million people. Today it has nearly 9.4 million—74 people Jewish—an almost threefold increase. This growth is the foundation of national survival amid an “Arab sea.” State policy and economic incentives were aligned around repatriation programs (aliyah, “ascent to the mountain”).

Now here’s a question: would repatriates have come to Israel if the country had been closed off behind an iron curtain? Would Jews from the USSR have gone to Israel if it, too, had been a closed country?

In one of my articles, I wrote: the main victory in war is civilizational. The main policy must be human-centered. Total methods of waging war do not work in an open information society. Prolonged moral and legal anesthesia only leads to social degradation. Long-term restrictions on citizens’ rights and freedoms breed destructive internal processes that corrode the state itself.

Ukraine’s future lies in building a society of free people and an economy of free entrepreneurs. Any attempt to impose a closed, restrictive model would mean civilizational defeat.

We also have to remember this: even if we do everything right and on time, the “demographic footprint” of the pandemic and the war will haunt Ukraine until the end of the century. But this should only strengthen our resolve to take decisive, effective measures to mitigate the demographic crisis—the greatest challenge to the existence of the Ukrainian nation in our history.

Please select it with the mouse and press Ctrl+Enter or Submit a bug

Login with Google

Login with Google