Decent Pension vs. Populist Noose: Why Limiting Civil Servants’ Salaries Will Harm Ukrainians’ Well-being

Bringing pensions up to a fair subsistence level is a requirement of justice that is beyond dispute. No citizen who has honestly dedicated years of their life to work—and no one in Ukraine at all, for that matter— should be forced to eke out a miserable existence.

However, the path to decent pensions does not lie through limiting civil servants’ salaries. On the contrary, this idea, recently proposed in the Verkhovna Rada, is yet another populist noose that will nothing but deepen Ukraine’s economic and social problems.

Salary restrictions will undermine the efficiency of state institutions, drive the economy further into the shadow and ultimately widen the gap between pension levels and real well-being.

The myth of “fairness” and the trap of paternalism

A state striving for prosperity must recruit the best talent available on the market. Only top-class managers can deliver economic growth. Settling for mediocrity because “pensions are low” is a deliberate choice in favor of future poverty.

The typical argument—“it’s unfair to have high salaries when pensions are low”—is deeply rooted in the paternalistic mindset of our society: “I worked for forty years, so the state owes me.”

But who exactly “owes”? It is not some abstract official—it is the Verkhovna Rada, elected by us, that sets the minimum pension. Shouldn’t we first examine the causes of low pensions instead of looking for simple but wrong answers?

Where is our money? The anatomy of collective poverty

Many people believe the myth: “I paid social security contributions into the Pension Fund.” But Ukraine’s Pension Fund (PFU) operates on a solidarity principle: your contributions immediately financed the pensions of those who retired before you. Your pension is now funded by those currently working (and during the full-scale war, in fact, also by taxpayers from our allies).

Raising pensions means current workers must pay higher taxes and contributions. Given that the Pension Fund is already subsidized by other taxes and international assistance, there is no room for maneuver. Raising taxes slows economic recovery, drives investors and businesses out of Ukraine and ultimately reduces revenues to both the budget and the PFU in the short and long term.

The numbers speak for themselves: there are 10.7 million social security contributors versus 10.4 million pensioners, plus nearly 3 million people with disabilities. That’s 0.83 contributors per recipient of social benefits. In Europe, the ratio exceeds two (2.6 for pensions specifically). In other words, our current predicament is almost three times more severe than the European average.

Moreover, over 35 percent of wages (and now as much as 38 percent, with the increased military levy) are in the shadow due to unreasonably high taxes on labor, thus critically shrinking the contribution base.

Demographics are equally discouraging: by 2035, the ratio of people aged 65+ to those aged 15–64 will rise from 26 percent to 33 percent.

The conclusion is simple and harsh: at this stage, there is no economic capacity to increase pensions without damaging the economy. Our solidarity system is heading toward a point where today’s forty-year-olds will be unable to receive state pensions in twenty years.

The vicious circle of poverty: paternalism breeds decline

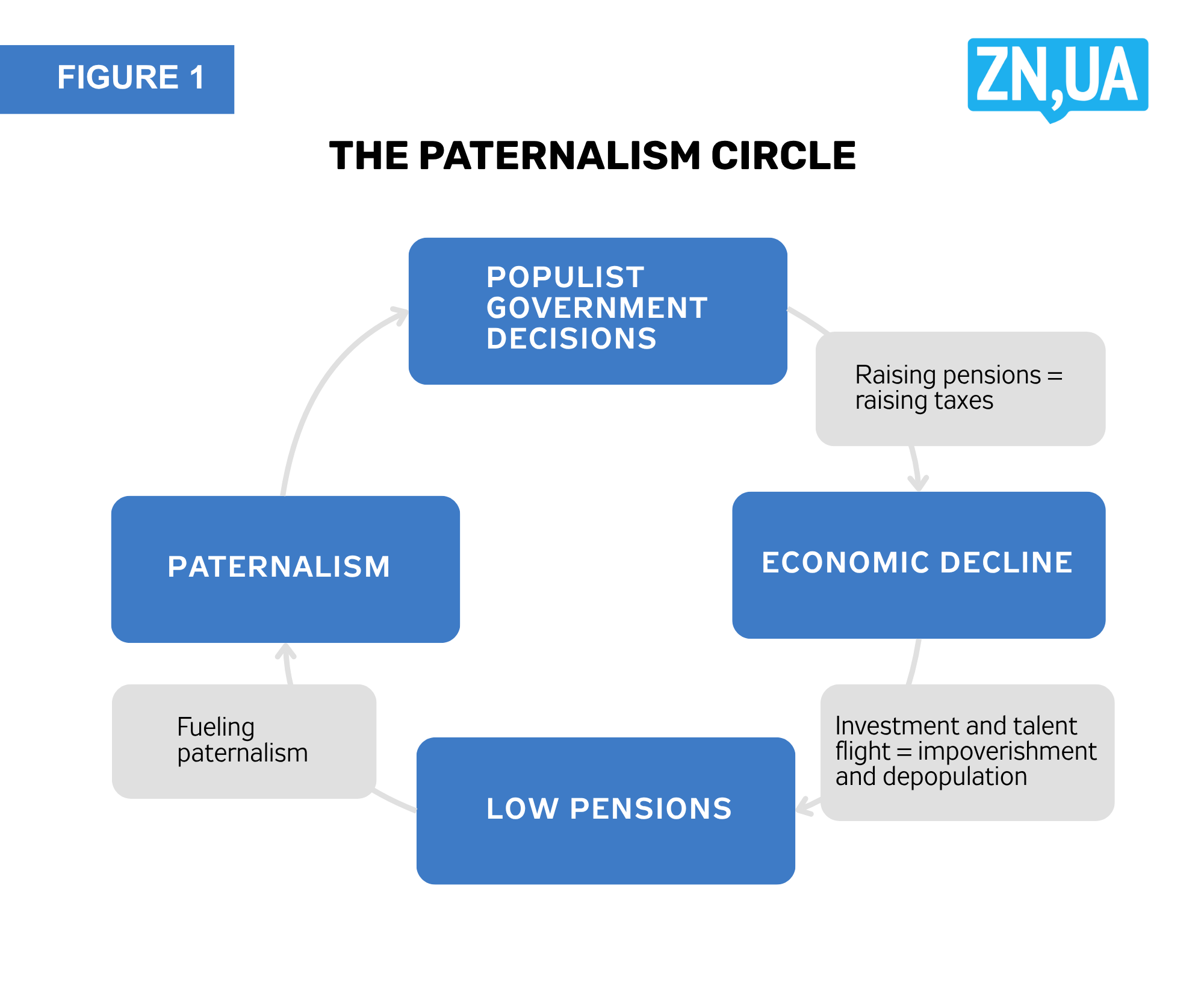

Low pensions are the result of past decisions by the governments we ourselves elected—governments chosen because of society’s lack of critical thinking and economic literacy. We are now trapped in a vicious circle of paternalism and decline (see Figure 1).

In fact, we’ve been wandering through the desert of modernity for 34 years, dragging along “Egyptians” who keep reminding us how good life was in Egypt and how delicious the ice cream tasted. They incite demands to raise social standards and cut civil servants’ salaries. These “Egyptians” are not just former Soviet Komsomol members, “security forces” or adherents of pro-Russian parties or the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate; they are also ignoramuses, populists and professional haters who can even hide behind the attractive mask of libertarianism.

This circle clearly shows that by choosing those who promise to raise pensions now, you will not get higher pensions (since it’s economically impossible); instead, you are guaranteed to see your well-being deteriorate in the future.

Why limiting civil servants’ salaries is a mistake

Firstly, it does not solve any of the fundamental problems of public administration. It is a non-systemic measure that does not improve institutional capacity, optimize administrative structures, introduce performance indicators or meaningfully influence budget expenditures. On the contrary, by degrading the quality of public administration, it reduces the state’s capacity in the short term.

Secondly, it leads to the risk of losing key personnel and expertise. The state must make public service more attractive for skilled and talented professionals. Instead, salary caps will accelerate the outflow to the private and civic sectors. In countries pursuing growth and prosperity, reforms focus on raising the professional level of civil servants.

Thirdly, low salaries foster corruption incentives. That is why Georgia, between 2004 and 2010, reduced corruption through a comprehensive package that included the simplification of procedures, automation, increased pay for key services and staff renewal through integrity screening. The effect came precisely from this systemic approach.

What should be done instead?

In 2022, our working group, formed jointly by the government and think tanks, developed a plan for public administration reform. It included structural and staffing optimization and a new motivation system for civil servants. The expected outcome: higher attractiveness and efficiency of the civil service while reducing costs by UAH 15 billion.

The state also needs a unified grading framework with external market linkage for “scarce” competencies and roles. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) likewise recommends balancing internal fairness with external competitiveness through transparent grades and total compensation (base rate + performance bonuses + non-monetary incentives).

Contracts with OKRs or KPIs should replace universal salary caps. These should include clear tasks, metrics and bonuses; for top positions—a variable share of remuneration tied to achievements, such as progress on government strategies or action programs. This approach also enhances transparency.

And, of course, anti-corruption reforms are needed, including automation of services, open data, clear regulations, public oversight and inclusiveness. In short, it is the infrastructure of integrity, not salary caps, that reduces corruption risks.

The path to prosperity: how to break the vicious circle

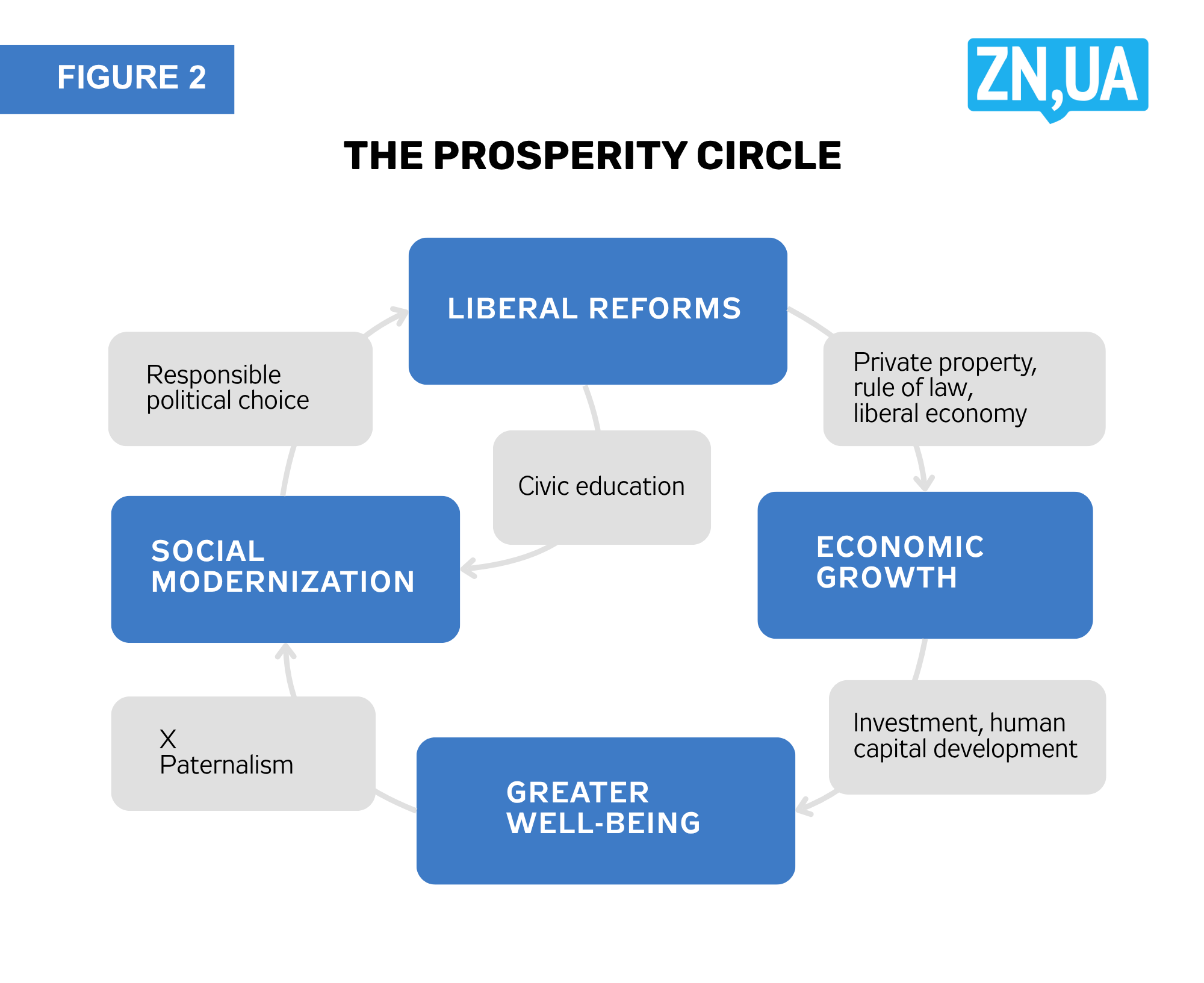

The only way out of this situation is through societal modernization and rapid economic growth. Figure 2 illustrates the circle that leads to prosperity.

By electing those who think in terms of economic development, you won’t get a pension increase immediately; but you will achieve higher well-being in the near future (three to five years).

Here is what the government must do to break the cycle of poverty in Ukraine:

- Establish inclusive cooperation with civil society;

- Invest in civic education and the development of new practices. Decentralization, homeowners’ associations and “check-ups” represent new practices; meanwhile, UAH 1,000 in government handouts, “national cashback” and “salary caps for civil servants” merely feed paternalism;

- Finally, carry out five top reforms: privatization, a regulatory guillotine, anti-corruption tax reform, customs reform and reform of the public procurement system. Concurrently, pension reform, public administration reform, judiciary reform and Criminal Procedure Code reform should be carried out;

- As a result, realize Ukraine’s vision as a country of opportunity with a people-centered state and responsible citizens.

What can actually be done to raise pensions?

Pensions can indeed be increased in the short term through fundamental changes—first and foremost, by de-shadowing the labor market and transforming Ukraine’s pension system. At the same time, consistent work on economic growth will organically raise wages, expand social security contributions and, ultimately, increase pensions.

It is crucial to understand that today’s pensions are not a punishment but the result of the nation’s political immaturity. The problem is not so much “bad officials today” as historically accumulated flaws in the economic and political systems.

The only way out of this vicious circle is through civic education, responsible government decisions on economic development (akin to “shock therapy”) and the cultivation of a social practice of personal responsibility—for one’s family’s well-being, one’s own pension, health, active longevity, education and productivity.

As a society, we need to grow up. We must move beyond the logic that pension increases depend on “the state’s goodwill” and instead recognize them as the result of our conscious political choice, control over authorities and cooperation. We should not expect easy solutions from populists. We must think and act. Only then will we break the circle of paternalism and build a state capable of creating dignified conditions in which all citizens can secure their own well-being.

Read this article in ukrainian and russian.

Please select it with the mouse and press Ctrl+Enter or Submit a bug

Login with Google

Login with Google