The Financial Trap. What Is Holding Back Ukraine’s Growth and Recovery

Large-scale fiscal stimulus by the government since the start of the war coexists with monetary restrictions imposed by the National Bank (NBU). This monetary–fiscal dissonance negatively affects the structure of aggregate demand, does not contribute to a rapid economic recovery and clouds the prospects for post-war reconstruction.

An overly loose fiscal policy with a significant budget deficit has been implemented in Ukraine since 2022, relying on substantial volumes of external official financing. The consolidated budget deficit of Ukraine amounted to 16.1 percent of GDP in 2022, 20 percent in 2023 and 17.6 percent of GDP in 2024. Over the past year—from August 2024 to August 2025—the deficit decreased to 15.1 percent of GDP.

International financial assistance and loose fiscal policy help sustain aggregate demand through the provision of public services, covering consumer expenditures of budget payment recipients and public investment in recovery and reconstruction.

However, loose fiscal policy in Ukraine has coexisted for three years with an extremely tight monetary policy. The current nominal key policy rate of the NBU is 15.5 percent, and the nominal effective rate on NBU operations is even higher—16.2 percent per annum.

Since early 2023, the NBU’s real effective rate has stayed firmly in positive territory. In the second half of 2023 and the first half of 2024, it ranged from +10.9 percent to 12.1 percent per annum. Later it gradually declined and in the first half of 2025 amounted to +1.1 percent.

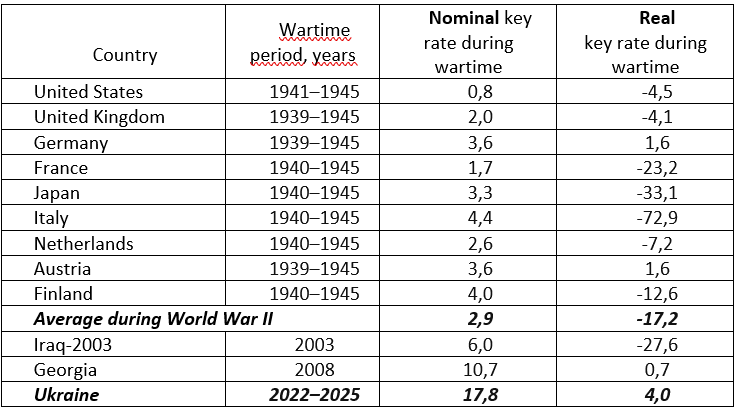

Such a level of central bank rates is a kind of record for a country at war. The data in Table 1 show that the real key rate during wartime was +0.7 percent in Georgia in 2008 and –17.2 percent on average in European countries, the US and Japan during World War II. In Ukraine, on average for 2022 – first half of 2025, the real key rate was +4 percent per annum.

Table 1. Average level of central bank key rates during wartime, percent per annum

The tightness of monetary policy has contributed to a contraction in bank lending, which in 2025 fell to a historic low—14.6 percent of GDP (in 2021—19.1 percent of GDP). Performing hryvnia loans this year dropped to 8.5 percent of GDP.

The dissonance of fiscal and monetary policies results in slowing real GDP dynamics and in radical changes in the GDP structure. In January–June 2025, GDP growth amounted to only 0.8 percent after an increase of 5.5 percent in 2023 and 2.9 percent in 2024.

The IMF positively assesses the NBU’s tight monetary policy during the war. In its latest program review report, the IMF states: “The NBU’s policy measures have so far been appropriate given the actual and projected inflation outcomes. …The NBU should continue to maintain tight monetary policy.” At the same time, the IMF recommends monitoring the effectiveness of the transmission of tight monetary policy to financial market indicators and the real sector of the economy.

In general, fiscal and monetary tools within the current macroeconomic paradigm affect the components of aggregate demand differently, stimulating public expenditure while suppressing private expenditure and investment.

These effects are already recorded in Ukrainian statistics as drastic shifts in GDP structure by expenditure components. In 2024, real public consumption increased by 37 percent compared to pre-war 2021, and real public investment saw an increase by 75 percent. At the same time, private investment in 2024 was 35 percent lower in real terms compared to 2021, and private consumption—by 19 percent. Moreover, real exports of goods and services in 2024 decreased by 40 percent compared to 2021.

In other words, macroeconomic processes in Ukraine since 2022 have been unfolding according to the classic scenario where loose fiscal and tight monetary policies are combined. Economic theory postulates that such a combination raises real interest rates and reduces the share of investment in GDP, which leads to production stagnation and simultaneously worsens the state of public debt.

This is exactly what happened in the United States in the early 1980s, when President Ronald Reagan launched tax reforms and significantly increased the budget deficit, while the Federal Reserve declared a war on inflation. At that time, the yield on long-term US government bonds exceeded 15 percent, and the yield on short-term securities was even higher. Such changes, combined with the appreciation of the dollar (also resulting from high rates), led to a severe recession in the American economy.

Renowned Indian professor J.R. Varma correctly points out that the ability of tight monetary policy to control inflation and food prices is realized by depriving people of access to money and thereafter to food.

According to a study by the European Central Bank (ECB), the 2020–2021 pandemic showed that under certain circumstances monetary and fiscal policies can reinforce one another. Eurozone authorities responded decisively to the Covid crisis by increasing public spending, while the ECB took measures to preserve price stability. Effective ECB actions ensured proper transmission of monetary policy across the euro area and benefited fiscal authorities by keeping government borrowing rates low and preventing jumps in sovereign risk premiums. These measures played a decisive role in minimizing uncertainty and contributed to a rapid economic recovery after the pandemic subsided.

In contrast to such approaches, even during the war Ukraine’s NBU focuses exclusively on suppressing inflation, ignoring the consequences of monetary restrictions for the credit process and GDP dynamics. In addition, as a result of chronically tight monetary policy, high rates in the domestic financial market translate into a constant increase in the state’s debt servicing costs.

This is exactly what we observe. Budget expenditures on interest payments for domestic debt, in relative terms, increased from 1.9 percent of GDP in 2021 to 3.1 percent of GDP in 2023 and 3.2 percent of GDP in January–July 2025.

The weighted average nominal yield of domestic government bonds at primary placements was 12.7 percent per annum in 2022 and 18.7 percent in 2023. In 2025, their nominal yield rose from 14.9 percent in January to 16.2 percent in July.

The real yield of hryvnia domestic government bonds in the first year of the large-scale war was negative, but since April 2023 it has been positive and followed an upward trajectory, reaching abnormal levels. The maximum level of real rates was recorded in March–April 2024—14 percent per annum. Subsequently, real rates gradually declined but remained in positive territory. In June 2025, the real ex post yield of domestic government bonds was +2 percent per annum.

Unproductive spending of public funds on inflated domestic government bond rates narrows the fiscal space for financing the state’s defense and socio-humanitarian expenditures. Insufficient volume of such expenditures reduces the country’s defense capability, increases human losses, and undermines the foundations of economic resilience.

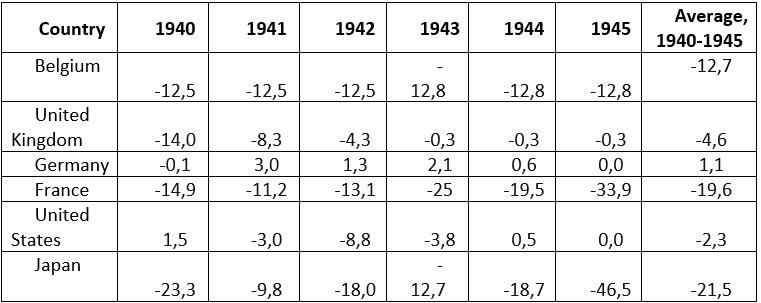

It is noteworthy that during World War II, real interest rates on government bonds in most war economies were negative. Table 2 presents data on real rates on domestic government borrowings in national currencies (with a maturity of one year or more) in 1940–1945.

In all countries in the sample, except the US and Germany, real rates in 1940–1945 were deeply negative, in many cases crossing the –10 percent per annum mark. Even in the US in 1944, when real rates turned positive, their level barely reached 0.5 percent.

Table 2. Real average annual yield of government borrowings in national currency during World War II, percent per annum

The high cost of borrowed capital and the low availability of bank credit in Ukraine already create, and will continue to create, obstacles to the recovery and reconstruction of the national economy. Therefore, monetary policy should become more accommodative and oriented toward support rather than neutralizing the expansionary effects of fiscal policy.

Easing monetary policy would positively affect the components of private investment and consumption in the structure of aggregate demand and would also indirectly increase aggregate supply through more active bank lending. Such simultaneous changes (generated by the rightward shift of both aggregate supply and demand curves) would become the driving force of output growth with minimal impact on the price level.

In addition, easing monetary policy would have little noticeable impact on prices given the fact that a significant share of domestic demand in Ukraine is covered by imports (imports of goods are twice the volume of exports). Moreover, the channels of monetary transmission through which NBU interest rates should influence inflation are ineffective. For example, the volume of term hryvnia deposits of the population in banks is less than 5 percent of GDP. And the average rate on hryvnia deposits now barely exceeds 10 percent, while banks receive 19 percent from the NBU for three-month certificates of deposit.

In the future, to overcome monetary–fiscal dissonance and create favorable conditions for economic recovery, it would be necessary to:

- radically reduce the degree of tightness of monetary policy and return to a symmetric design of interest rates;

- abandon the practice of the National Bank placing three-month deposit certificates;

- introduce instruments to stimulate banks’ lending activity, including easing prudential requirements.

At the same time, it would be advisable to lower interest rates on new domestic government bond placements to a level approaching the projected inflation rate for the coming year.

Lower interest rates in Ukraine’s economy would stimulate private consumption and investment, leading to growth in aggregate demand and more active restoration of production capacity. In parallel, lower interest rates would have a positive impact on the cost of servicing public debt, reducing the likelihood of a debt crisis in the future.

Please select it with the mouse and press Ctrl+Enter or Submit a bug

Login with Google

Login with Google