Losses for Workers and Gifts for the Chosen—The Contrast Between Government PR Projects and Reality

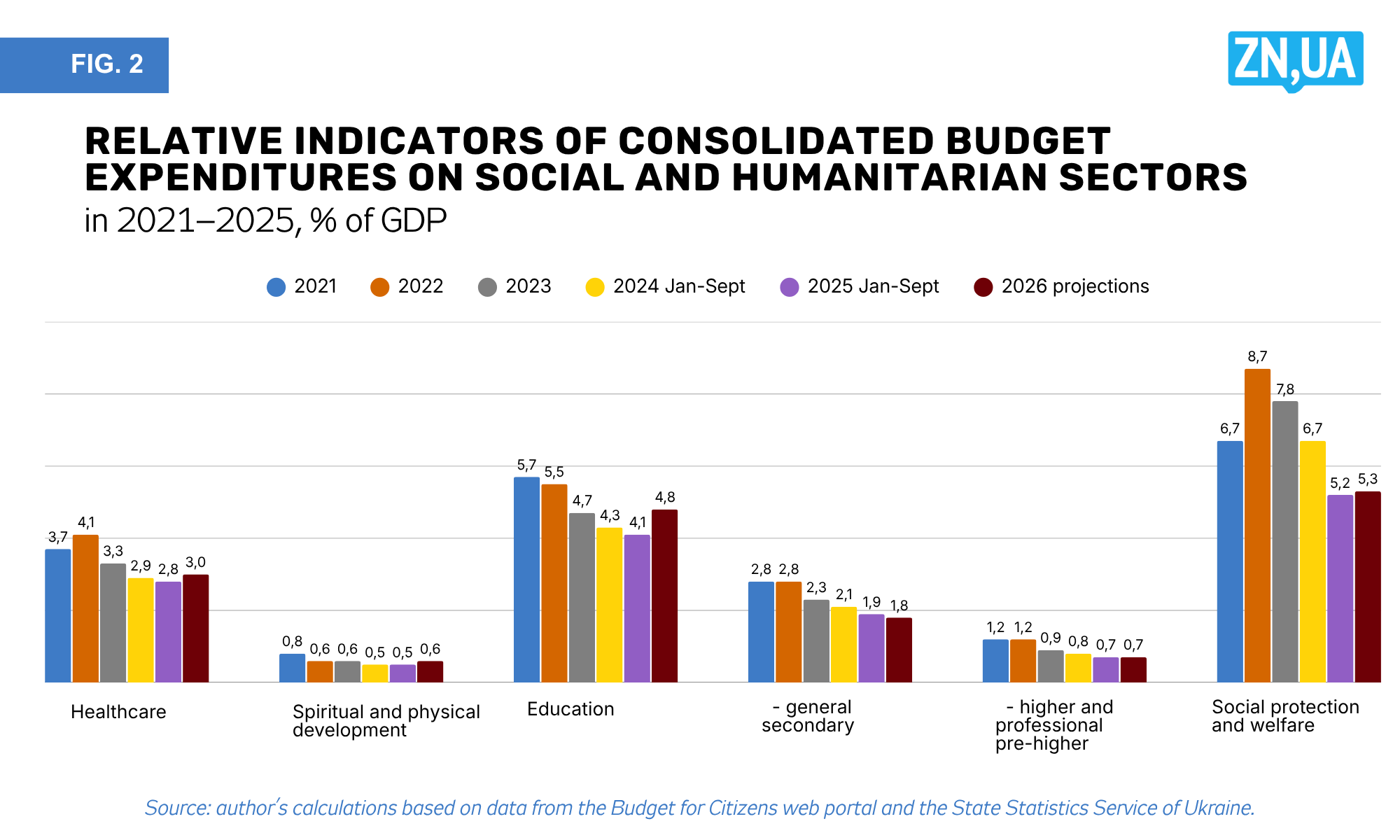

During wartime, the social and humanitarian sector has faced a significant reduction in budget financing, both in real terms and relative to the overall budget. Expenditures of the consolidated budget on human capital development and social protection decreased from 17% of GDP in 2021 and 19% in 2022 to 12.6% of GDP in January–September 2025. For 2026, the draft budget envisions an increase in such expenditures by 1.1 percentage points of GDP, but even then they will remain 3.3 percentage points of GDP below their 2021 level.

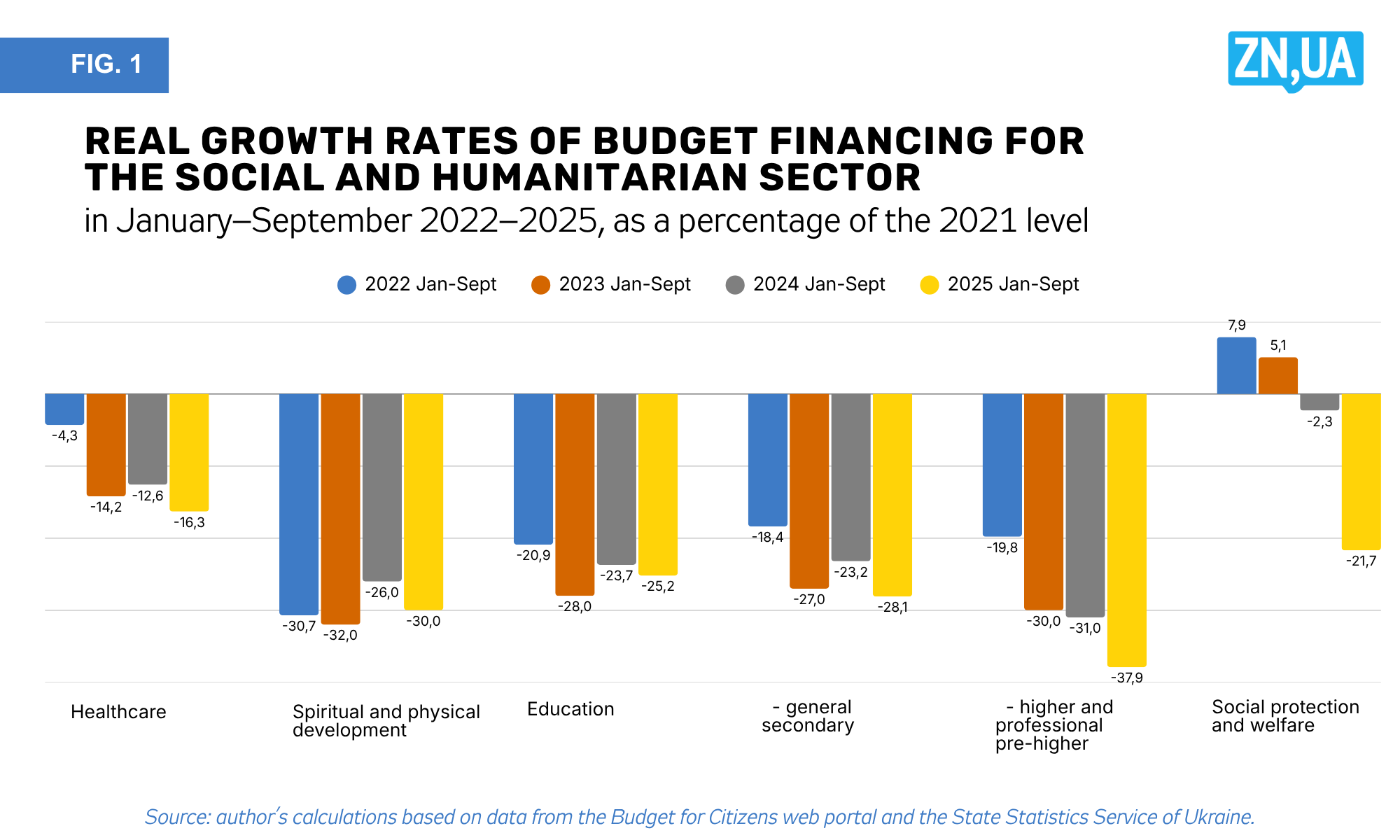

A breakdown of social and humanitarian spending shows that, in real terms, financing for healthcare in January–September 2025 fell by 16% relative to the same period in 2021, for education by 25%, and for spiritual and physical development by 30% (see Figure 1). Notably, financing for higher and professional pre-higher education from the general budget fund decreased in real terms by 44%. Social security and welfare programmes were also reduced by 2%, even though the government introduced new initiatives for internally displaced persons (IDPs), veterans and war-disabled individuals.

Since the onset of the full-scale invasion, the relative shares of funding for these sectors have also decreased. For example, expenditures on education fell from 5.7% of GDP in 2021 to 4.1% of GDP in January–September 2025 (see Figure 2). The main burden of budget cuts was borne by general secondary education, which saw a decrease of 0.9 percentage points of GDP compared to 2021. Expenditures on healthcare, after rising from 3.7% of GDP in 2021 to 4.1% in 2022, subsequently declined to 2.8% of GDP in January–September 2025. The reduction in the range and quality of medical services in public healthcare institutions amid mass injuries at the front and in the rear has taken on the features of a socially dangerous phenomenon.

Expenditures on social security and welfare fell to 5.2% of GDP in January–September 2025, significantly lagging behind the levels of 2021 and the early years of the war. The highest level of funding in this area was recorded in 2022 at 8.7% of GDP. In 2023–2025, the relative volumes of financing declined under the influence of fairly high inflation and the lack of indexation of many types of social payments and benefits. In addition, more stringent eligibility conditions were introduced for IDP payments in 2024.

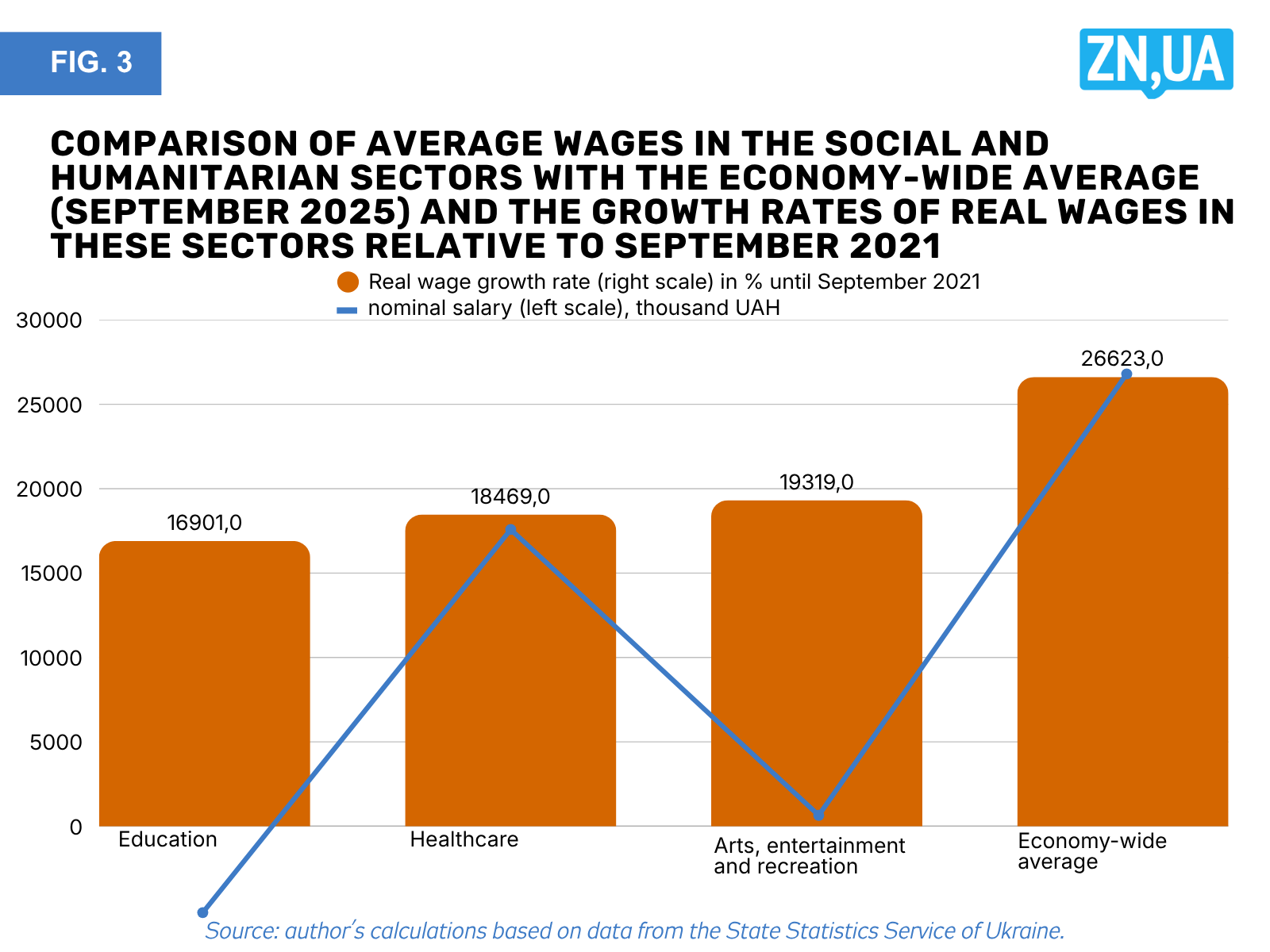

The reduction of budget financing for the social and humanitarian sphere directly affected the wages of its workers. Figure 3 shows the average nominal wages in education, healthcare, arts and sports in September 2025, which ranged from 63% to 73% of the national economy average.

The average wage in the education sector in September amounted to 16,900 UAH, and in healthcare — 18,500 UAH. Meanwhile, according to calculations by the Ministry of Social Policy, the actual subsistence minimum for able-bodied persons in June 2025 equalled 11,500 UAH. This means that if a family of workers in the social and humanitarian sphere has at least one dependent, such a family falls below the subsistence minimum.

Figure 3 also shows the rate of decline in real wages in the social and humanitarian sectors (measured by the food price index) relative to September 2021. While the average real wage across the economy increased by 4% (from October 2021 to September 2025), all analysed sectors recorded declines in real wages. Thus, in education, the real wage in September 2025 was almost one-quarter lower than in September 2021. The decline reached 19% in arts and sports and 4% in healthcare.

Since the beginning of the war, the government has indexed old-age pensions, but indexation of social benefits and wages has mostly not taken place. At the same time, the real value of fixed, non-indexed wages and benefits decreased by 39% between October 2021 and September 2025, when calculated using the official Consumer Price Index (CPI), and by 44% when calculated using the food price index. This indicates a significant decline in purchasing power and the spread of poverty among workers in various public sector branches.

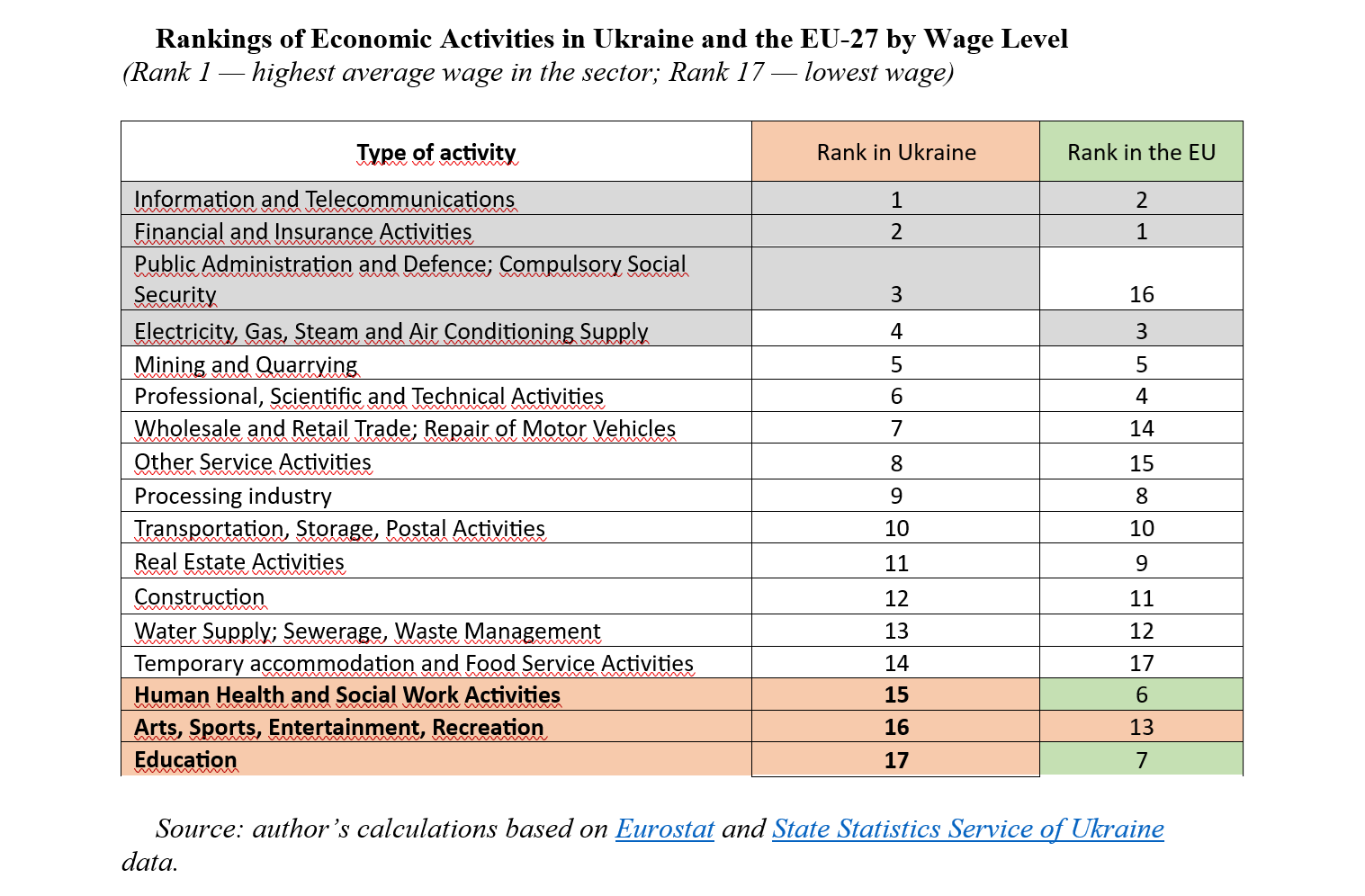

To assess wage indicators in Ukraine’s social and humanitarian sectors relative to other types of economic activity, we relied on data from the State Statistics Service of Ukraine and Eurostat. Our aim was to compare the rankings of different sectors by average wage levels in the 27 EU member states and in Ukraine. The results of the analysis are presented in the table.

The data clearly demonstrate the undervaluation of labour in Ukraine’s human capital development sectors relative to other industries. This has resulted both from the prioritisation of defence-related spending during the war and from society’s long-standing discriminatory attitude toward these sectors over the course of decades.

In Ukraine, the education, arts and healthcare sectors exhibit the lowest wage levels among all types of economic activity. Accordingly, they occupy the lowest positions (15th, 16th and 17th) in the sectoral wage ranking. In contrast, in the 27 EU member states, labour in these sectors is valued far more highly, and the sectors themselves hold mid-range positions in wage rankings. For instance, in the EU-27, the healthcare and social work sector ranks 6th out of 17 by average wage level, while the education sector ranks 7th (see table).

The reduction of real budget financing and real wages in the public segment of Ukraine’s social and humanitarian sphere has already produced and will continue to produce a series of negative consequences.

First, it intensifies the moral and physical suffering of workers in this sphere during wartime, increases the scale of poverty among the employed and worsens the quality of medical and educational services available to the population. In the long term, this leads to lower labour productivity in the economy, premature mortality and a decline in the quality of human capital.

Second, it perpetuates the negative trend of external migration. The UN estimates the number of Ukrainian migrants since the start of the war at 6.9 million people. As security risks in Ukraine gradually decrease, Ukrainians will not be motivated to return home if wage levels in Ukraine fail to reach even the level of social benefits or minimum wages in the EU.

As a result of the significant deterioration in working conditions since the beginning of the war, there has been a decline in the number of staff employed in educational institutions, cultural institutions and healthcare facilities. According to data from the State Statistics Service, over four years (up to October 2025) the number of employees in the education sector decreased by 192,000 people, or by 17% compared to pre-war levels; in healthcare—by 138,000 people, or by 19%; and in the arts, sports, and recreation sector—by 17,000 people, or by 14%.

Unfortunately, the pressure of accumulated problems in the social and humanitarian sphere does not prompt the Ukrainian authorities to address them systematically but rather encourages the generous distribution of gifts to consumers of certain social, educational and medical services.

After three and a half years of a grueling war, the authorities have finally turned their attention to school teachers and certain groups of doctors. The 2026 budget plans to allocate 41.8 billion UAH for indexing the wages of teaching staff in general secondary education — by 30% from January 2026 and an additional 20% from September 2026. The budget also provides 5.1 billion UAH for wage indexation for primary care and emergency medical care physicians.

However, even after the wage indexation in September 2026, school teachers will have an average salary of 25.8 thousand UAH, which still does not reach the current national average. It should also be noted that in September 2025 the average salary in education barely exceeded $400 per month, and a year later (after indexation) it will likely amount to around $560 per month. These figures, evidently, fall far short of the $4,000 per month that President Zelenskyy promised to teachers on the eve of the 2019 elections.

The last months of this year have been marked by a wave of PR initiatives that will further worsen the overall situation in Ukraine’s social and humanitarian sphere while allowing the authorities to appease a significant share of the electorate or selected groups of the population.

From the standpoint of economic efficiency and social fairness, the following programmes should be considered problematic:

- 1,000 UAH in winter support for all Ukrainians (more than 10 billion UAH in budget expenditures);

- up to 3,000 km of free travel on Ukrainian Railways (17 billion UAH in company losses to be covered from the budget);

- the school meals “reform” (13.8 billion UAH in budget expenditures);

provision of housing under the “yeOselya” programme, excluding housing for IDPs (11.4 billion UAH); - “demographic development measures” (24.5 billion UAH), which include: increasing maternity benefits for uninsured women (1.1 billion UAH); raising the childbirth benefit to 50,000 UAH (6.8 billion UAH); increasing childcare benefits to 7,000 UAH (6.5 billion UAH); launching the “yeYasla” programme for childcare for children aged one to three (8.9 billion UAH); a one-time “School Starter Pack” payment for first-grade pupils (1.2 billion UAH).

It is also troubling that such “amusements,” as their creators envision them, are meant to take place against the backdrop of a deteriorating situation along the line of contact, insufficient coverage of the material and technical needs of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, and the absence of stable military and economic support for Ukraine from international partners.

According to Roksolana Pidlasa, Сhairman of the budget committee of the Verkhovna Rada, Ukraine’s military expenditures, including external assistance, will amount to $106 billion in 2025. In 2026, the authorities plan to increase them to $120 billion, including $60 billion in international assistance. In reality, the actual spending by international partners on military assistance to Ukraine is lower: over the past year, it amounted to €42.2 billion, or $49.4 billion.

Yet even with annual external support of $40–60 billion, Ukraine’s military budget dramatically lags behind the military budget of the aggressor, which stands at more than $200 billion (taking into account preferential loans from Russia’s defence-industrial complex banks and the reactivation of old weapons stockpiles).

By all logic, any state fighting for survival against a more resource-rich and reckless neighbour should not allow itself to distribute “helicopter money” to the population or launch expensive social programmes with minimal public benefit. Unfortunately, logic and common sense are not always integrated into the practice of public administration in Ukraine. Going forward, to preserve the Ukrainian state, it is essential to concentrate all available resources on conducting effective military and defence operations against the aggressor and on ensuring the functioning of the social and humanitarian sphere as the foundation of the country’s future development.

Read this article in Ukrainian and russian.

Please select it with the mouse and press Ctrl+Enter or Submit a bug

Login with Google

Login with Google