Free Fall Of Russian Science

More than 24,000 different sanctions have been imposed on Russia. The vast majority of them are directed against the economy of the aggressor state. At the same time, the myth that sanctions do not work is being actively cultivated, with economic successes being demonstrated as proof. However, such “successes” can be created on paper, as shown by our recent research, which has proved that Rosstat (Russia’s Federal State Statistics Service) artificially underestimates inflation in Russia, putting it at about one-third of the real indicator.

Meanwhile, there are areas that are almost untouched by sanctions, such as science, which is considered “outside of politics,” plus “freedom of academic thought,” etc.

Despite the absence of official sanctions packages against Russian science, unofficial “treats” have been used against it (more on this later). So, in science, unlike Russian statistics, we have a fundamental opportunity to objectively assess the impact of sanctions. In fact, in this publication, we will provide some interesting figures.

But let's start with the fact that sanctions against Russian science, albeit unofficial ones, were imposed after all. Of course, the more correct term is “restrictions,” but in essence, these are the same sanctions.

Sanctions against Russian science

So, the “restrictions” took different forms and included the cancellation or reduction of funding, termination of cooperation with Russia, closure of joint projects or removal of scientists associated with the Russian regime. Foreign companies closed their R&D departments in Russia. Sanctions include the imposition of restrictions and bans on the supply of equipment and reagents, the refusal of foreign scientists to participate in scientific conferences and international events organized by Russia, joint research projects, etc. In addition, some Russian scholars (especially those who remained in the aggressor state) became a kind of outcasts and somebody no one wants to engage with.

And there were all sorts of unpleasant little things for Russian scientists that are rarely mentioned, but which can make scientific life quite difficult. For example, visa restrictions, flight restrictions (European skies are closed to Russian planes, so scientists from this country need to use additional hubs such as Turkey or the UAE to reach their destinations), problems with payments (Visa and Mastercard have left Russia, and most Russian banks have been sanctioned), the fall of the ruble (resulting in increased costs) and so on.

You want to publish an article, but you can't pay because you are a Russian scientist, and many international publishers cannot receive payments from Russia as part of economic sanctions packages. So it turns out that you are willing, but unable.

Many international organizations have suspended Russia's membership, including the International Union of Speleology, the European Association of Urology, the International Geographical Union, the European Federation of Psychologists’ Associations, the European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education, the European Foundation for Management Development and many others. By the way, together with the Ministry of Education and Science in 2025, I initiated a campaign to expel those Russian organizations that are still members of international organizations. In the first month, two international organizations (the Association for Dental Education in Europe and the European University Continuing Education Network) have already excluded representatives of the aggressor state from their membership list, and several others have initiated a status review procedure for Russian institutions.

And let's not underestimate the degree of mental unsoundness of the Russian authorities. If there is an opportunity to shoot themselves in the foot, they are sure to do it.

Russian sanctions against Russian science

The Russian government took offense to the Western scientific world and decided not to take into account the indexing of its scientists' publications in international databases (such as Scopus or WoS) when evaluating the results of scientists or organizations. This, of course, could not but affect the quantity and quality of international publication activity.

Russian academic institutions usually do not allow the scholars who left Russia because of their stance in relation to conscription or war to continue working, forcing them to look for a job outside the country.

In addition, Russia has launched a campaign against its own scientists in a fit of paranoia and spyware. Their publications in international journals or speeches at international conferences, as well as participation in international projects, were seen as a violation of state secrets and treason. What is more, they also resulted in arrests, criminal cases and real prison terms. Some scientists were lucky enough to get 12 years in prison (the physicists who developed the Russian hypersonic missile program, Anatoly Gubanov and Valery Golubkin, were sentenced to this term. Such is karma). So jokes about “sharashkas” (Soviet scientific institutions where imprisoned scholars worked) may soon become a reality.

Oh, and to make sure that Russian science has no future, the Russian government has made a strong-willed decision to withdraw from the Bologna process.

This is not an exhaustive list of sanctions and restrictions, but rather a generalized view of it.

Impact of sanctions on Russian science

Quite predictably, Russia claimed that all of this was beneficial for its science. However, fortunately for us, in this case we cannot rely on Rosstat data or simply take Russia's word for it; external objective metrics should be used instead.

The easiest way to assess the impact of sanctions on Russian scientific activity is to examine bibliographic databases, since one of the main scientific products is a scientific publication. The largest and most well-known databases today are Scopus and Web of Science (WoS).

Scopus is currently larger than WoS. It has more than 1.8 billion citations since 1970; more than 84 million records; more than 17.6 million author profiles; more than 25,000 active titles and 7,000 publishers. The coverage of journals in Scopus is higher than in WoS (42,000 vs. 34,200) and wider (includes life sciences, humanities, etc.), which is vital for comparison. Therefore, the object of analysis is Scopus data.

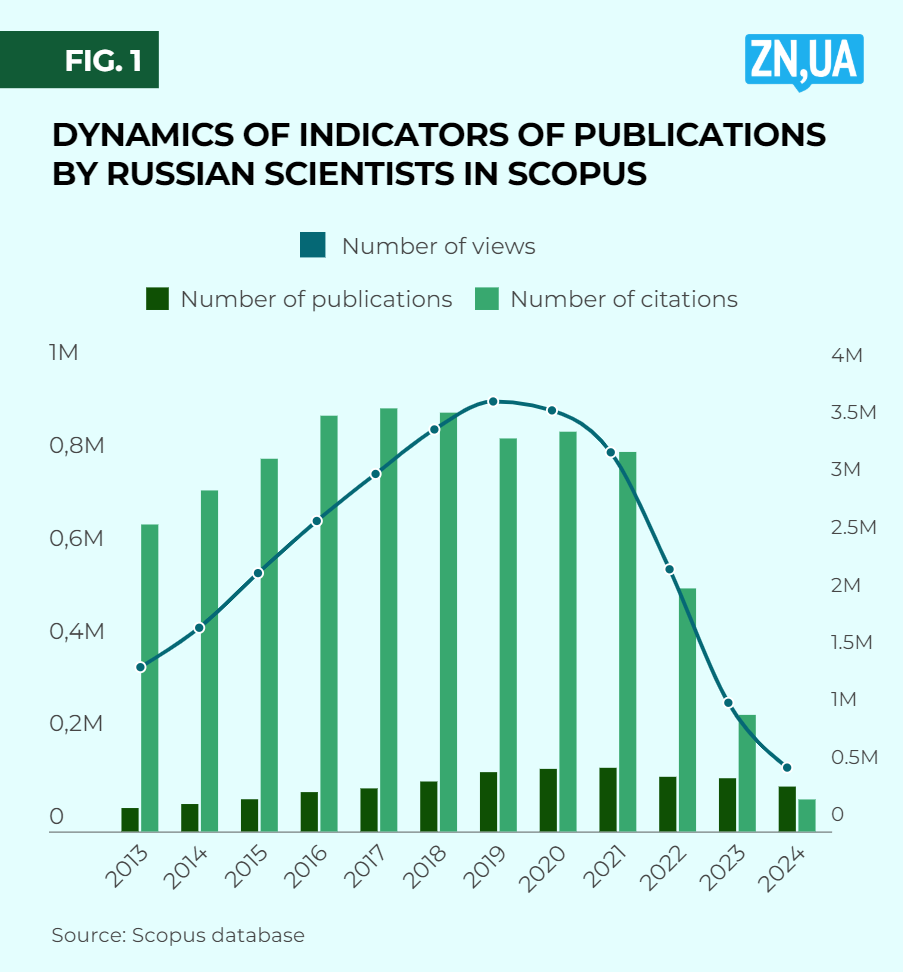

The basic metrics offered by Scopus to assess scientific activity are as follows: number of publications, number of citations, number of views.

Note that the data for 2024 is incomplete and is likely to improve slightly for this year, but it is not a dramatic change, so it is quite relevant to illustrate the state of affairs and trends.

As you can see, before the pandemic, Russia's scientific activity was growing steadily and reached a certain plateau at the top, but in 2022 something happened, and Russian science entered a state of rapid uncontrolled decline. In the three years since the start of the full-scale invasion, the number of citations of Russian scientists' articles has fallen by 92 percent, and the number of views of their papers has fallen by 85 percent. Basically, this is all you need to know about how sanctions don't work. By and large, Russian science has been erased from the international space.

One of the most striking examples (and the most expected due to the status of a “rogue country”) is the number of publications by Russian scientists at scientific conferences, which fell by 40 percent in 2022 and continued to fall in 2023.

To demonstrate how this works, let's take a look at a field in which Russia has traditionally been strong: physics. One of the most respected journals in this field is The Journal of Physics Conference series, organized by the Institute of Physics in the United Kingdom.

In 2021, Russian authors presented almost 6000 papers in the series. In 2022, this number plummeted to 1029. In 2023, only 124 Russian papers were presented. As you can see, the drop in the key field is 80–90 percent, an almost complete annihilation.

You may say that these are purely quantitative metrics, but perhaps Russia has simply moved to a qualitatively new level. In order not to waste your time on discussions and descriptions, we will present some qualitative metrics in the table below.

|

Metric |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

2023 to 2021 |

|

Share of publications in the Russian Federation that are in the top 10 percent of the most viewed in the world, pcs |

20,415 |

13,852 |

5,017 |

4,650 |

-75% |

|

Share of publications in the Russian Federation that are among the top 10% most viewed in the world, percent |

14,9 |

11,8 |

4,4 |

4,8 |

-70% |

|

Number of views per publication |

22,5 |

18 |

8,9 |

4,9 |

-60% |

|

Field-Weighted Views Impact* |

1,19 |

1,03 |

0,61 |

0,62 |

-49% |

Field-Weighted Views Impact (FWVI) shows how the number of views of a particular organization or author's publications correlates with the average number of views of all other similar publications in the same database. That is, how much the views of this entity's publications differ from the average level of views globally for this database.

As you can see, everything is fine in terms of quality: steady negative growth.

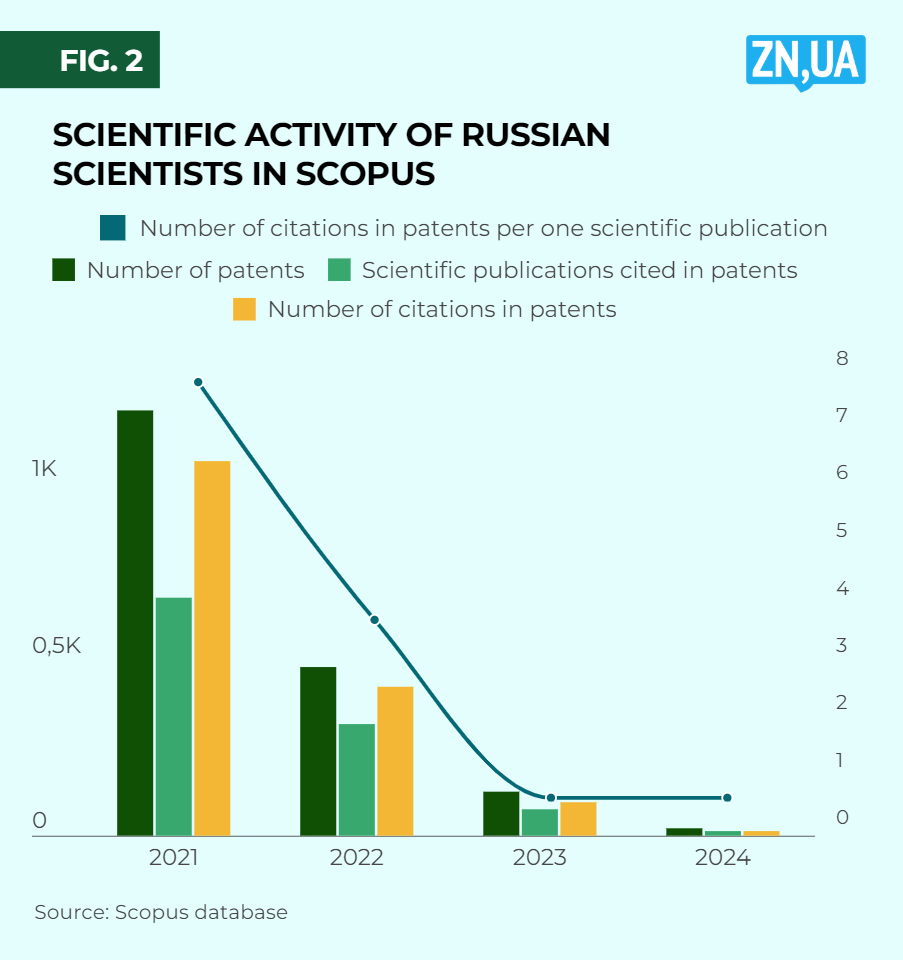

For additional verification, let's use the following metrics for assessing scientific activity available in Scopus: number of patents; scientific publications cited in patents; number of citations in patents; number of citations in patents per scientific publication.

The results for the period from 2021 to 2024 are shown in the figure below (the same warning applies to 2024).

Visually, we get full confirmation of the aforesaid conclusions. Russian science has ceased to be a generator of useful things, it no longer creates anything in terms of inventions. As you can see, the decline is absolute, by all metrics in 2024 it was more than 90 percent.

So when people tell you about the greatness and power of Russian science, don't waste time arguing, just cite this data.

Obituary (epilogue)

Sanctions against Russian science are working, and quite effectively, erasing the aggressor country and its latest propaganda myth about the greatness of Russian science, which the world cannot do without.

Despite this, Russian science is still a powerful mouthpiece of Russian propaganda and has great potential to harm humanity. Much of its potential is currently being used to develop military technologies. There is a scientific thought behind every conventional drone or cruise missile.

For example, on July 8, 2024, a Russian cruise missile hit the Okhmatdyt Children's Hospital in Kyiv, killing two people and injuring more than 30. A joint investigation by the Security Service of Ukraine and the Prosecutor General's Office found that the X-101 missile used in the attack was manufactured in the second quarter of 2024 by the Raduga design bureau. “Although under Western sanctions, Raduga and its production facility, the Dubna Machine-Building Plant, design and manufacture many of the weapons used by Russia in its war with Ukraine, including military aircraft (Su-25, Su-34) and missiles (X-55, X-101, etc.). These enterprises are located in the “science city” of Dubna, 110 kilometers north of Moscow.

Therefore, the fight against Russian science is also a fight against the occupying army and opposition to the war. And in the academic world, efforts to combat it should not stop, but only intensify.

Sanctions against Russian science should be brought to the official level. Those Russian scientific and educational institutions that have openly supported the war, promoted the annexation of Ukrainian territories, and provided financial and material support to the occupying army should be included in sanctions lists and expelled from the international academic environment.

International publishing houses should reconsider their policy of “territorial neutrality” and finally recognize the simple and obvious fact that Crimea is Ukraine, Donetsk is Ukraine, and stop playing into the hands of the aggressor country by labeling Ukrainian territories as Russia.

The Ukrainian ISSN center should stop helping the occupiers, and even at the expense of Ukrainian taxpayers: finally gather their will and do something about the dozens of Russian journals whose registration they confirm every year and directly contribute to their presence in the international scientific community.

In short, there is still a lot of work to be done, but there are results. And yes, sanctions are working.

Please select it with the mouse and press Ctrl+Enter or Submit a bug

Login with Google

Login with Google