Ukraine Faces Winter Gas Crisis: Ready or Not?

Following Russian missile attacks targeting Ukraine’s natural gas infrastructure and the harsh winter of 2024–2025, rebuilding gas reserves for the next heating season may become one of Ukraine’s most pressing strategic challenges.

Of course, Ukraine’s reliance on imported gas to refill reserves ahead of winter is neither new nor unusual. Since gaining independence, Ukraine has consistently consumed more natural gas than it has produced domestically, covering the shortfall through imports.

Prior to 2015, Ukraine imported gas from Russia. Since then, it has sourced gas exclusively from European energy markets.

For instance, in the pre-war 2021, national gas consumption reached 28.7 billion cubic meters (bcm), while domestic production totaled just 19.8 bcm.

Ukraine’s near self-sufficiency in gas during 2022–2023 resulted not from increased domestic production, but from a sharp contraction in demand. That drop was caused by Russia’s war and the resulting loss of control of densely populated areas of eastern and southeastern Ukraine, as well as a sharp contraction in industrial activity.

As a result, gas consumption in 2022 declined by approximately a third, to 19.5 bcm, which was almost offset by domestic production, which was also at 18.5 bcm.

Despite wartime efforts by both public and private producers to ramp up domestic output, total gas production rose by only 2.2% last year, and still has not recovered to pre-war levels. In 2021, production stood at 19.80 bcm, while in 2023, it reached only 19.12 bcm.

Meanwhile, in 2024, by my estimates, gas consumption rose roughly 10% to 21.8 bcm, driven by a tentative industrial rebound and greater use of gas-fired power generation.

In light of the damage sustained from the Russian strikes against production infrastructure, I estimate that in 2025, total domestic gas production will decline to 18.16 bcm, while consumption will rise to 22.9 billion cubic meters. This will result in a supply-demand gap of approximately 4.73 bcm (Figure 1).

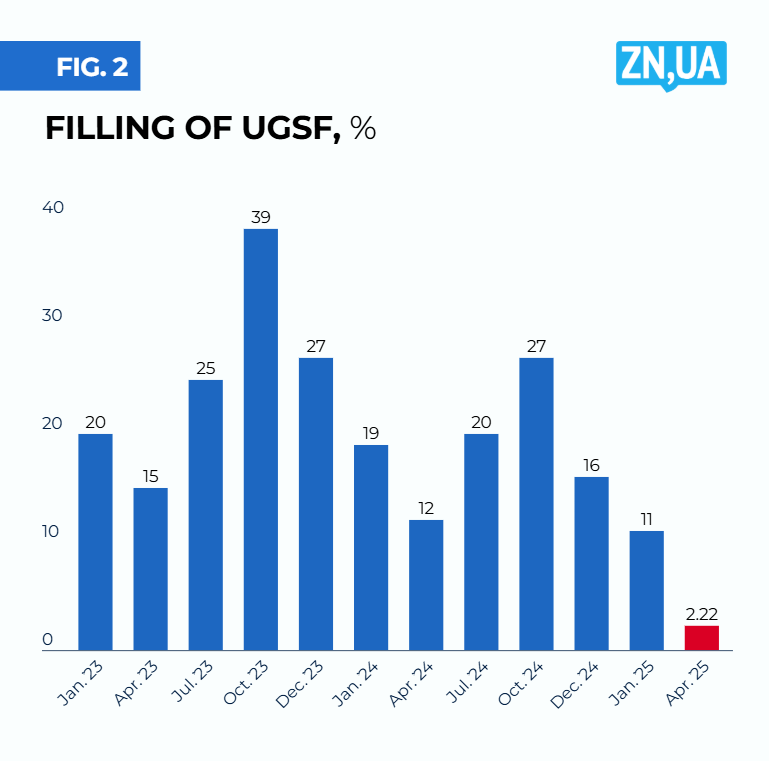

Residual volumes in Ukraine’s underground gas storage facilities (UGSF) are insufficient to bridge the projected shortfall, as only about 0.67 bcm are expected to be in storage at the beginning of the injection season.

Moreover, considering the seasonal spike in consumption during the winter months, Ukraine will need to accumulate at least 8.2 billion cubic meters of active gas in storage, the same as last year’s minimum threshold. A reserve target of 9 bcm would provide a strategic buffer against potential supply shocks.

To achieve this, considering the projected level of domestic output, I estimate that Ukraine will need to import between 5.5 and 6.3 billion cubic meters of gas during 2025. By comparison, the most recent projections from Naftogaz, Ukraine's state-owned oil and gas giant, put the import requirement at 4.6 bcm.

The financial cost of this import volume is estimated to be between $2.5 billion and $3 billion.

How to Fund Gas Imports

Naftogaz and the Ukrainian government persistently face and resolve the issue of financing gas imports each year. In a properly functioning energy market, this challenge would be largely mitigated, requiring only short-term credit lines to bridge seasonal demand in winter.

Gas pricing in Ukraine has long been politically fraught, leaving the domestic gas market chronically underdeveloped. Today, the majority of gas consumers receive supplies from Naftogaz at state-regulated prices, which are well below import parity:

- Households pay $0.20 per cubic meter.

- Thermal power plants (TPPs), combined heat and power plants (CHPs), gas turbine and piston installations pay between $0.34 and $0.43 per cubic meter.

- Gas distribution system operators (DSOs) receive gas for technological losses at a regulated price of $0.18 per cubic meter.

By contrast, the market cost of imported gas exceeds $0.48 per cubic meter.

This pricing structure was sustainable only when reliance on imports was low. However, under the current scenario, with substantial import requirements of higher-cost European gas, Naftogaz will struggle to bridge the gap between rising procurement costs and end-user tariffs without significant foreign aid.

A partial solution came in the form of a government-imposed Public Service Obligation (PSO) requiring Ukrnafta, a state-owned oil and gas extraction company that is a subsidiary of Naftogaz, to sell all of its extracted gas to Naftogaz at a fixed price of $0.29 per cubic meter.

While this measure is a logical attempt to support Naftogaz’s financial stability, its scale is limited: the total volume amounts to only 1.17 bcm annually, far short of what is needed.

Historically, successive Ukrainian governments’ populist aversion to raising domestic gas prices left Naftogaz perpetually reliant on state funding. This support typically came via domestic governmental bond issuance (OVDPs) and direct capital infusions into Naftogaz’s charter capital.

This approach not only rendered Naftogaz persistently loss-making, but also imposed a heavy burden on the state budget. Effectively, this constituted untargeted subsidies for cheap gas, benefitting all consumers, including those fully capable of paying market prices.

The resulting distorted pricing environment not only undermined fiscal stability but also created opportunities for manipulation and misuse of “cheap” gas allocations.

By 2014, these subsidies reached unsustainable levels: budget support for Naftogaz consumed 5% of Ukraine’s GDP, or slightly over $336 million.

Only in 2015, under pressure from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), did Ukraine begin to implement genuine gas market reforms. In April of that year, under the government of Arsenii Iatseniuk and with active support from Naftogaz, gas prices were raised to market levels, an increase of nearly 4.5 times.

This shift was accompanied by introduction of a targeted housing subsidy system to protect vulnerable households.

The results were transformative. Naftogaz shifted from a fiscal black hole to a net contributor to the state budget. In 2016, the group paid $2.7 million in taxes and dividends, which was around 10% of Ukraine’s state revenue. By 2017, Naftogaz’s contributions reached 2.64 million, covering approximately 15% of total state budget revenues.

Regrettably, earlier gains from market liberalization have largely unraveled. A confluence of internal political resistance and external pressures has led to the reintroduction of extensive state control over Ukraine’s natural gas market.

By 2021, this shift had already begun to manifest in financial instability at Naftogaz, forcing the company into another frantic search for liquidity ahead of the 2021–2022 winter heating season.

Faced with depleted financial reserves, Naftogaz urgently needed to import 900 million cubic meters of gas but lacked the capital to do so. In September 2021, the company formally notified the government, saying that it required $2.95 million in total funding, including $1.06 million specifically for gas imports.

In response, the government opted for an indirect support mechanism: instead of direct budget transfers, it decided to utilize the retained earnings of the Gas Transmission System Operator of Ukraine (GTSOU) from 2020 to 2022. A contractual agreement was arranged between GTSOU and a Naftogaz subsidiary, under which $1.15 million would be transferred to cover part of Naftogaz’s financing gap.

The transaction was authorized by governmental decree and executive order issued by the Energy Ministry. Following these approvals, GTSOU disbursed the funds, and Energy Minister Herman Halushchenko publicly reported the transfer at a cabinet session on Oct. 6, 2021.

Through this decision, the government effectively provided Naftogaz with $1.15 million in financial support, drawing on the undistributed profits of the Gas Transmission System Operator for 2020–2021, funds that, under normal circumstances, would have been remitted to the state budget as dividends.

In practical terms, this move amounted to quasi-budgetary financing of Naftogaz.

Following the onset of the Russian full-scale invasion, Ukraine’s natural gas imports significantly declined between 2022 and 2024, mainly due to a sharp drop in domestic consumption. In 2022, a portion of the limited imports was financed through a $350 million concessional loan from Canada and other donors, as well as credit lines extended by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD).

In parallel, Ukraine heavily relied on drawing down its transitional gas reserves stored in storage facilities. Before 2022, the country typically exited the heating season with residual gas volumes of 3.5 to 4.5 bcm, excluding the 4.6 bcm of active gas required to maintain system pressure and thus not available for withdrawal.

However, by the end of the current heating season, only around 0.67 billion cubic meters of gas is expected to remain in storage. This indicates that the shortfall in imports in recent years has been largely offset by depleting nearly all available reserves from UGSF.

That strategy, however, has now reached its limit. With only 0.67 bcm of transitional gas left in storage, Ukraine will no longer be able to meet its needs without resuming imports (Figure 2).

To finance natural gas imports for the upcoming winter, Ukraine will require an estimated $2.5–3 billion. Naftogaz intends to cover part of this amount with donor assistance, but it is unlikely that external partners will be able to bridge the funding gap fully. At present, only $0.4 billion in donor support has been publicly pledged, leaving a sizable funding gap to close.

One potential avenue is the conventional route, direct budgetary financing. However, this path faces obstacles, particularly from the IMF, which closely monitors Ukraine’s fiscal expenditures.

The IMF is unlikely to endorse significant budget allocations to Naftogaz unless accompanied by a transition to market-based gas pricing.

The government may explore alternative domestic sources, such as tapping into the resources of state-owned enterprises, similar to the 2021 approach with the Gas Transmission System Operator, or seeking funding from state-owned banks.

Yet, at present, there appear to be no state enterprises with substantial unallocated financial reserves.

Securing external loans from Western commercial banks or international financial institutions is also expected to be challenging without a credible plan to ensure cost recovery, primarily through higher tariffs for end-users.

Meanwhile, issuing sovereign bonds on global markets remains unrealistic under current conditions.

The second pathway is a market-driven approach, a return to gas market liberalization and aligning gas prices and tariffs for transmission and distribution services with market levels, as was done in 2015.

Ukraine already has experience with such reforms, and the subsidy mechanism to support vulnerable consumers is well-established and functioning effectively. This strategy would significantly improve the country’s ability to attract external financing and bring Western gas traders back into the market.

However, predicting the government’s course of action remains challenging, particularly amid persistent speculation about possible elections once active hostilities subside.

I do not expect the authorities to reintroduce market-based pricing soon. Ad hoc or non-systemic measures—for instance, mandating large industrial consumers to purchase exclusively imported gas or similar interventions—are also possible.

However, the time is not on Ukraine’s side. The country’s maximum guaranteed natural gas import capacity is approximately 50 million cubic meters daily, or about 1.5 billion cubic meters per month.

Importing the 4.6 bcm planned by Naftogaz would require at least three full months of sustained imports at peak capacity. To inject 6 bcm into storage would take four months, assuming uninterrupted imports via all available routes: Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, and Romania (via the Trans-Balkan pipeline).

However, it is unclear whether these volumes can be reliably secured on the market within that narrow timeframe, especially at maximum daily rates. Therefore, at least five months should be allocated to secure and inject the necessary volumes. This implies that large-scale imports must begin as early as May to ensure sufficient gas is in storage by Nov. 1.

Please select it with the mouse and press Ctrl+Enter or Submit a bug

Login with Google

Login with Google