Three Sides, No Translator: Can Ukraine’s Customs Connect with Society and Business?

A successful customs policy is not limited to tariffs, procedures and oversight. It also requires mutual understanding among the regulator, the business community and civil society. Unfortunately, the current interaction among these three actors resembles a conversation in three different languages—with no interpreter.

The Institute for Analytics and Advocacy, in cooperation with the Technology of Progress NGO, has analyzed the barriers impeding this tripartite dialogue and proposed a set of measures to overcome them. Below are the key findings and an analytical perspective on the prospects for improving engagement and communication in the customs sphere.

Silence of partners

Despite formal commitments to openness, the mechanisms of communication between the customs service, business community and the public remain surprisingly weak. A case in point is the Public Council at the State Customs Service—an advisory body intended to represent public interests—which is, to put it mildly, ineffective. Its composition has not changed in four years. Transparency is lacking, as the customs service does not properly publish its responses to the Council’s proposals. Most critically, consultations often amount to one-way information sharing rather than substantive explanations or genuine consideration of business and civil society perspectives.

Of particular concern is the limited participation of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). They are effectively excluded from the policymaking process, which creates a structural asymmetry of influence in favor of larger economic actors in possession of resources to advocate for their interests.

Survey data illustrate this imbalance:

- Only 22 percent of business representatives believe they have any influence over customs policy;

- In contrast, 45 percent of civil society activists feel they can contribute to policy change.

These figures not only indicate weak business engagement but also suggest a broader demotivation among entrepreneurs who see little value in participating in processes they perceive as lacking credibility.

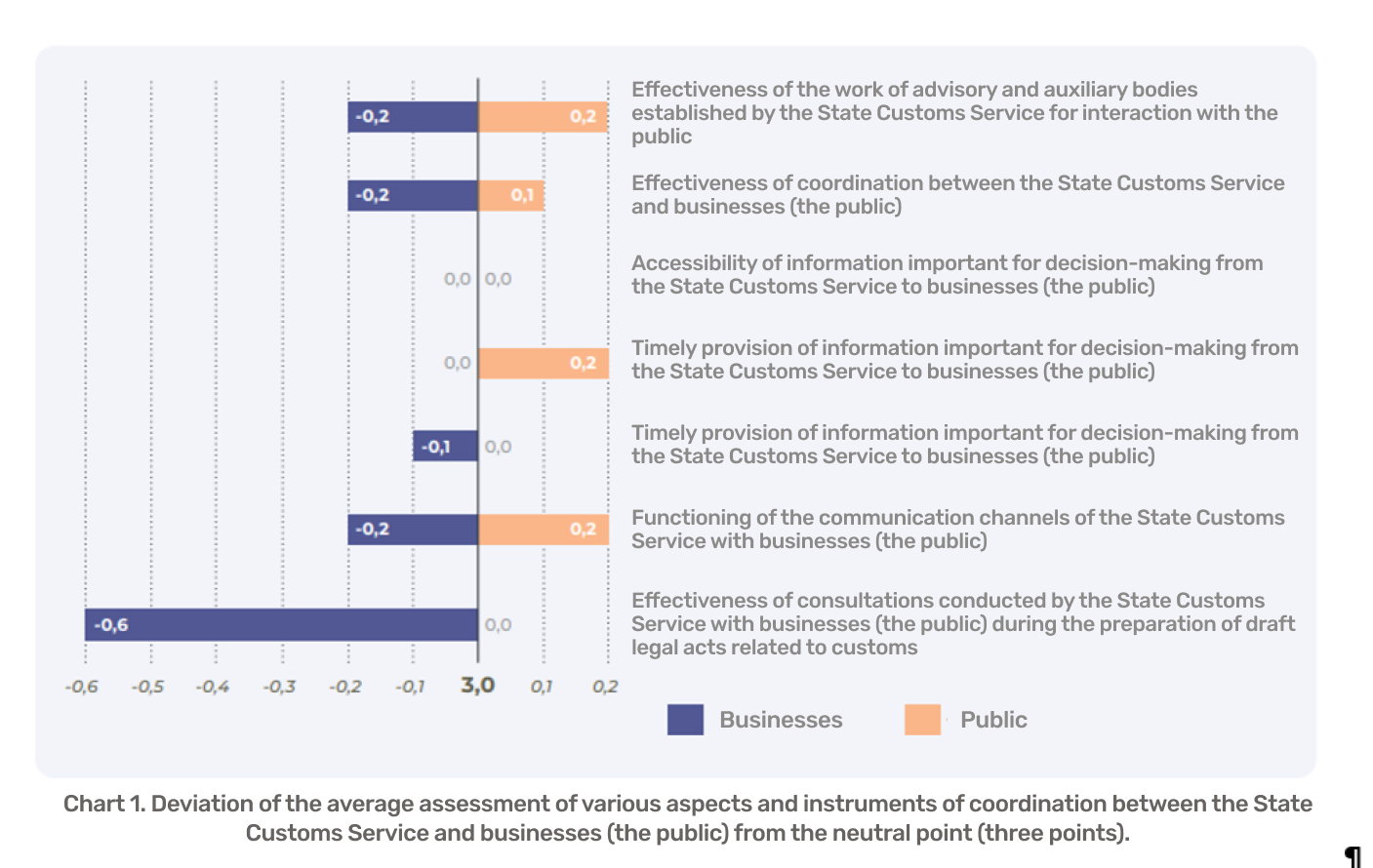

As part of this research, we surveyed representatives of both business and civil society organizations to assess their interaction with the State Customs Service—specifically, the effectiveness of coordination, the accessibility and timeliness of information and the functionality of consultation mechanisms regarding acts and regulations.

Infographics can be used to demonstrate differences in the perception of various aspects of coordination, using a neutral rating of three:

— In all parameters presented, the public perceives the work of the State Customs Service better than businesses, which interact more closely with customs authorities.

— The effectiveness of consultations in the preparation of legal acts received the least approval from businesses—about -0.6 (i.e., 2.4 points), while the public rates this aspect higher.

— Businesses are more critical of the effectiveness of coordination, the work of advisory bodies and communication channels, while the public has a better opinion of these aspects.

— The work of advisory bodies is not rated the worst, but it is still below neutral. Businesses gave this aspect a score of 2.8, while the public gave it a score of 3.0, i.e., on the verge of neutrality. This may indicate low awareness among SMEs about the activities of such bodies or skepticism about the real impact of councils on decision-making.

The reasons for the discrepancies lie in their different roles. Business is a practical player that evaluates results first and foremost: whether their concerns were taken into account, whether their work was made easier, whether they received a response. The public, on the other hand, is more focused on processes—monitoring, outreach and advocacy—and a higher tolerance for procedural uncertainty is part of their activities.

The course of action is obvious: expand consultations with business, open information channels and create feedback tools accessible to all parties concerned, work on the effectiveness and visibility of advisory structures.

The unrealized potential of the Public Council

The Public Council holds significant potential as an important component in the triangle of customs interaction. In addition to exercising public oversight over customs operations, it can propose regulatory initiatives and serve as an information hub for both businesses and citizens. However, these functions are only partially fulfilled due to several structural issues.

First, an outdated regulatory framework (Cabinet of Ministers Resolution No. 996).

The Council operates under a regulation that fails to reflect current realities, including full-scale war, digitalization and demands for transparency. Amendments introduced during martial law allow for the non-publication of documents, undermining the principle of public oversight. This has resulted in a lack of transparency and diminished public trust in an institution that should be both open and accountable.

Second, the absence of public feedback.

The State Customs Service is formally required to respond to the Council’s decisions. However, its official website does not provide information on which proposals have been accepted or rejected, nor the reasons behind these decisions. Responses are typically delivered by mail or announced during meetings, without broader public access. As a result, it is impossible to evaluate the Council’s effectiveness or actual impact.

Third, the lack of membership rotation.

The Council’s current composition has remained unchanged for over four years, despite the requirement for rotation. The decline in engagement and initiative is therefore hardly surprising.

Fourth, the underrepresentation of small businesses.

SMEs are effectively excluded from Council membership unless they form a civil society organization, and the standard framework does not explicitly recognize SMEs as a distinct category in the operation of the body. Ironically, one of the main users of customs services—SMEs—is deprived of influence on policymaking.

Fifth, insufficient transparency.

The number of published minutes and reports does not match the actual number of Council meetings held, and those that are published often lack detail regarding outcomes.

In practice, the Public Council is unable to adequately fulfill either its oversight or representative functions. Immediate institutional reform is needed—this includes a review of its legal status, procedural modernization and renewal of its membership.

These issues are not merely technical—they are systemic. The challenges observed in the Public Council under the State Customs Service reflect broader dysfunctions that may affect every public council across Ukraine. Addressing these shortcomings would represent a significant step toward restoring public trust, including trust in Ukraine’s customs policy.

What needs to be changed

To address problems in the area of customs regulation, the first priority should be the development of a digital platform for customs-related explanations. Such an online system would provide access to interpretations of customs legislation, enable users to submit inquiries, receive real-time consultations and track the status of their requests. This initiative is urgently needed: 61 percent of businesses report a lack of accessible advisory support, which leads to legal uncertainty and reliance on intermediaries. The platform should be modeled on the State Tax Service's ZIR (Eyesight) system and supported by the HelpDesk with expanded competence to handle a broader range of inquiries.

A second key step is the revision of Cabinet of Ministers Resolution No. 996 to restore the mandatory publication of Public Council documents, even under martial law, and to grant the Council an advisory vote in personnel decisions. Public councils should operate as open platforms for civic engagement in policymaking, not as closed clubs. This will require removing restrictions on transparency and legally enshrining rights to participate in selection processes, staff appraisals and institutional performance evaluations.

The third component of the reform should be the establishment of a transparent system for responding to Public Council decisions. The Ministry of Finance and the State Customs Service must be required to issue written public responses to the Council’s proposals within ten working days. Without this feedback loop, it is impossible to assess the Council’s impact or the effectiveness of its work. This will require amending relevant regulations and introducing mandatory public disclosure of such responses.

To improve the Council’s reporting practices, annual plans and reports should include concrete examples of results achieved, especially those that directly address business concerns. The current reporting lacks specificity, undermining its informativeness and public trust. Future reports should focus on results and include analytical data on accepted and rejected proposals.

Last but not least, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) must be formally included in the coordination process. This can be achieved through dedicated consultation mechanisms, such as subcommittees or separate councils. At present, SMEs lack direct access to the Public Council, even though they form the backbone of Ukraine’s foreign trade activity. They must be granted direct representation in advisory structures.

Ukraine’s customs system is about more than control—it is about service delivery, trade facilitation and transparency. Modernization must therefore proceed not only through technical upgrades but also through organizational change that includes all stakeholders. In other words, genuine reform requires dialogue in which all participants have a voice, not just a seat at the table. Building an effective interaction between customs authorities, businesses and the public is not merely a democratic norm—it is key to reducing corruption, improving the business climate and ultimately strengthening the economy.

This publication was prepared with the financial support of the European Union. The content is the sole responsibility of the Institute for Analytics and Advocacy and the Technology of Progress NGO and does not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.

Read this article in Ukrainian and russian.

Please select it with the mouse and press Ctrl+Enter or Submit a bug

Login with Google

Login with Google