Gasoline Independence: How Was It Built and How Much Does It Cost?

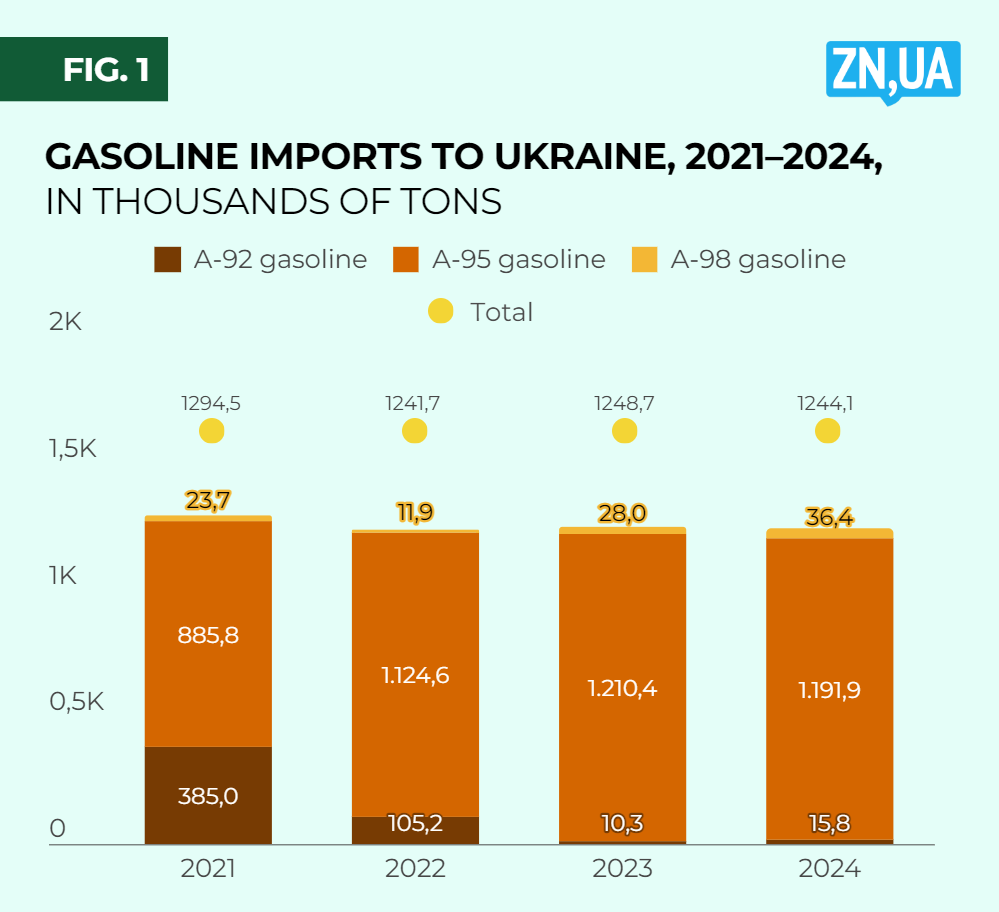

Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, gasoline imports to Ukraine have remained unchanged at 1.24 million tons and virtually meet the volumes of 2021. The difference is that then 85 percent (1 million tons of gasoline) came from Belarus. And starting in 2022, the same million tons will be imported from Europe. This means that life without energy from Russia and Belarus is not a fiction, but a reality (see Figure 1).

A new world

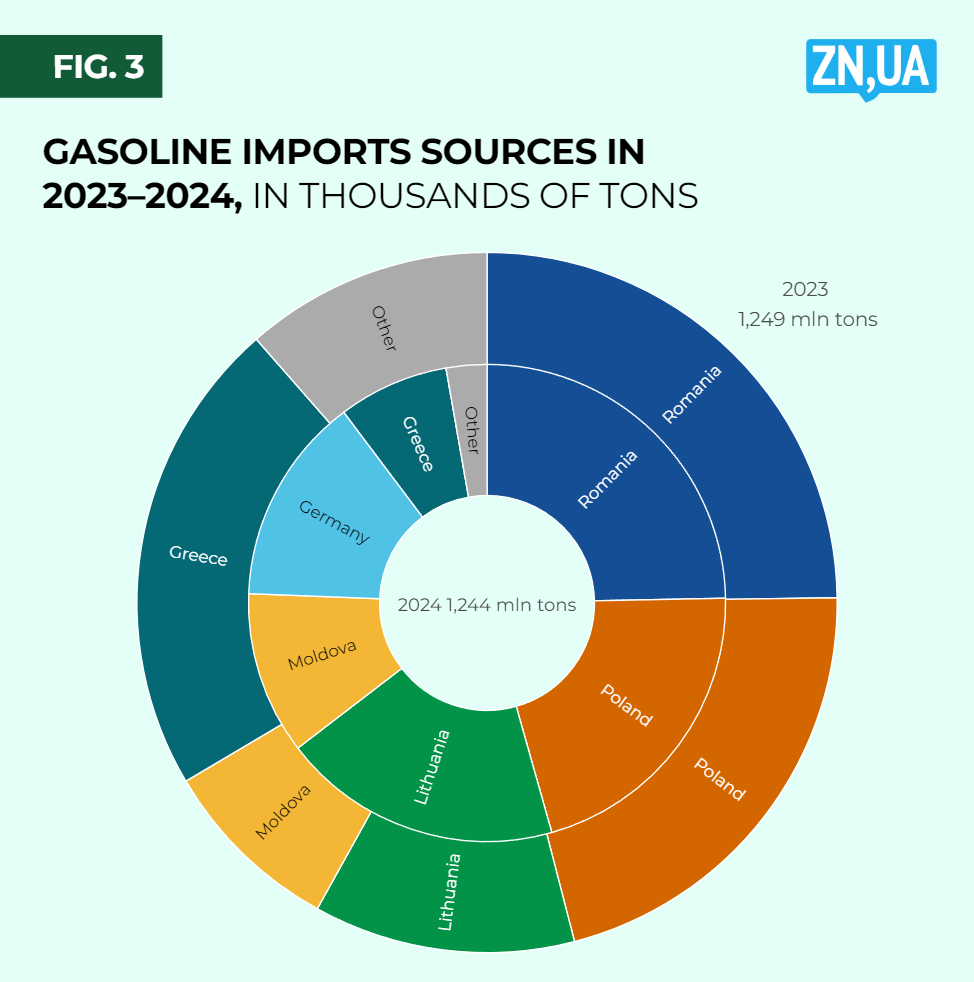

As with the supply of the most popular product, diesel fuel, last year saw the optimization of logistics routes. Over the year, the geography of gasoline imports narrowed from 16 to 11 countries. Hungary, Georgia, the Netherlands, Estonia and Croatia left the list. These supplies were sporadic, so the market did not feel any discomfort because of their disappearance.

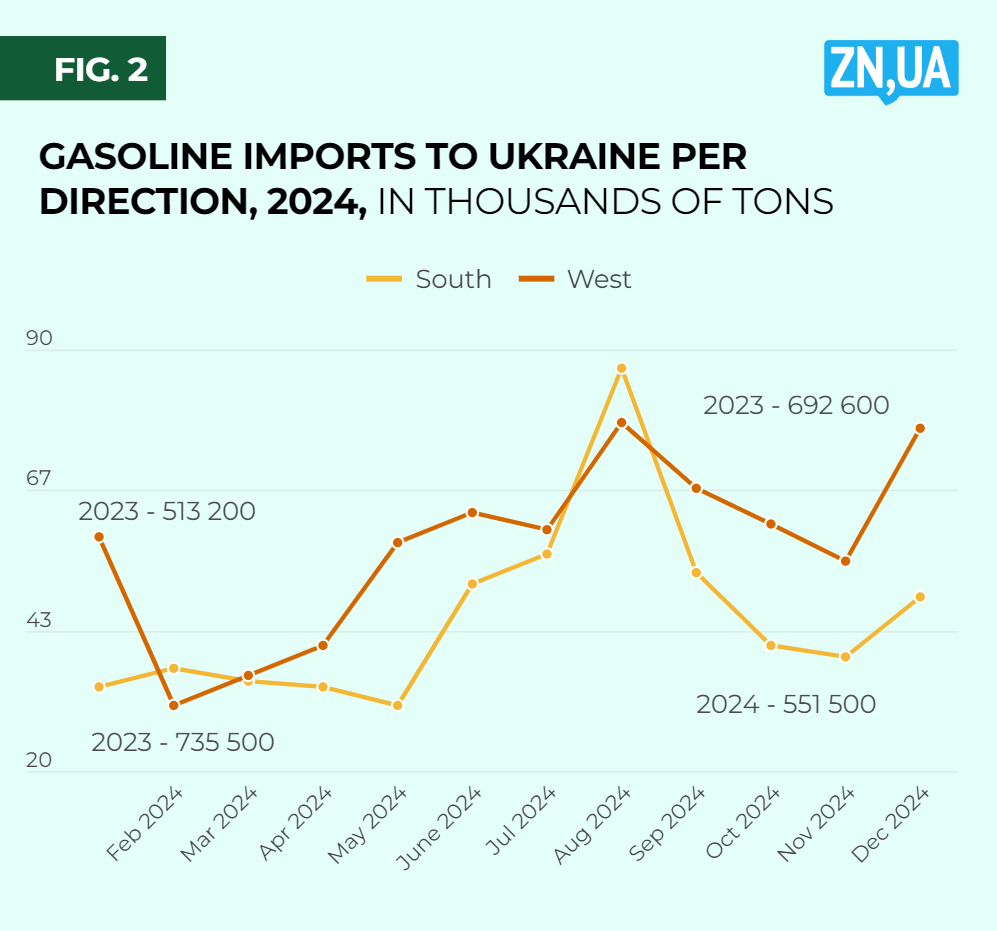

Gasoline flows shifted from the South to the West: slightly more than half (56 percent) of total imports entered through the western border. Compared to 2023, this direction saw an increase by 35 percent (692,600 tons).

At the same time, the South lost 25%, mainly due to a decline in volumes from Greece. This source was sporadically successful when the market lacked traditional suppliers. For example, in early 2023, when Ukraine and Europe were preparing for an embargo on imports of petroleum products from Russia, or on the eve of the increase in excise taxes and VAT in the summer of 2023 and in August last year (see Figure 2).

The main reason for the reorientation of gasoline imports from the South to the West is the better price of the product in countries where pricing is based on Baltic Sea prices. Firstly, they were more favorable than the Mediterranean (southern) ones. Secondly, the surplus of gasoline in Northern Europe is becoming increasingly noticeable, due in part to a decline in exports to Africa.

The result of these consumer-friendly processes was the return of price formulas for Ukraine to the “pre-war” level of 2021.

The Lithuanian refinery in Mažeikiai, which is well known to the Ukrainian market and drivers, owned by the Polish concern Orlen, fought especially hard for the consumer. The refinery increased shipments to Ukrainian companies by 56% (to 235,900 tons) and thus returned to 2021 volumes.

In addition to attractive prices, Orlen Lietuva also had to take technical measures, including the reconstruction of the Mockavos railway terminal (which transfers fuel from the wide Soviet gauge to the narrow European gauge on the border of Lithuania and Poland). As a result, throughput capacity increased from 90 to 170,000 tons per month.

The key beneficiary of these changes was West Oil Group (WOG), which doubled its purchases of Lithuanian gasoline to 98,700 tons. It should be noted that this chain has been a long-standing customer of the Lithuanian product.

Orlen strengthens its position

Poland and Romania continue to share 46 percent of total gasoline imports, with volumes remaining remaining almost unchanged over the year (see Figure 3).

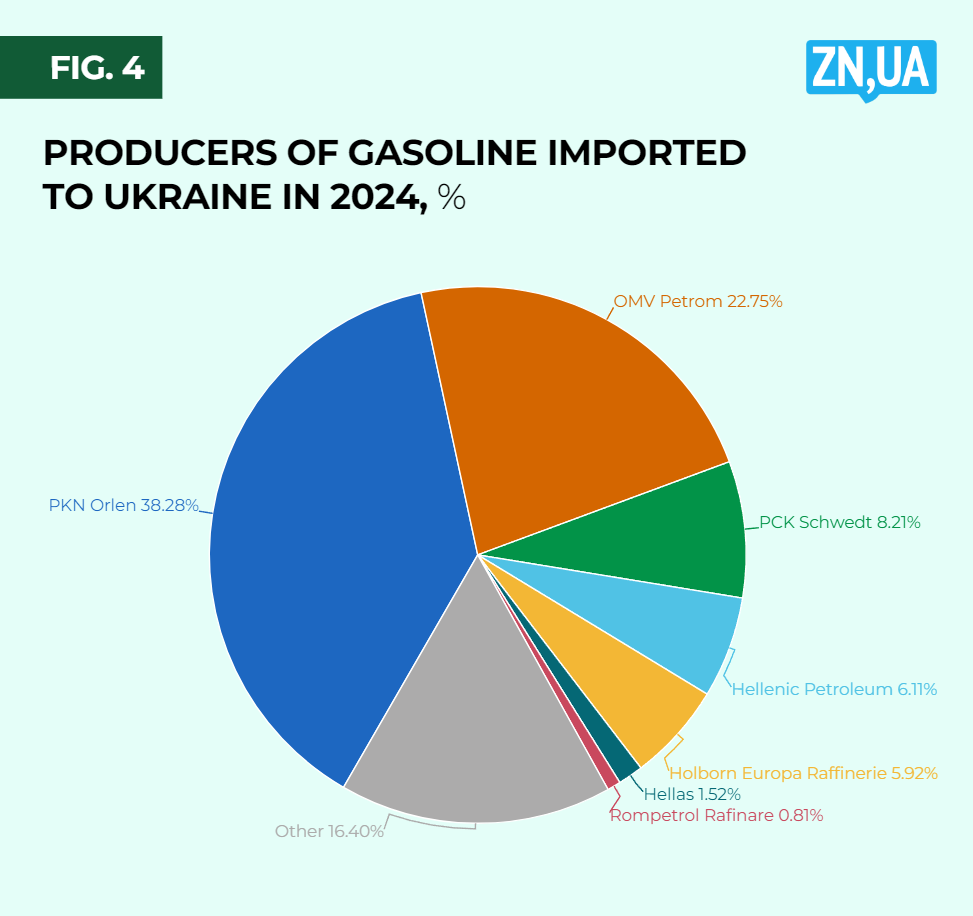

Orlen accounted for 87 percent of imports from Poland, adding 60 percent (240,400 tons) over the year. In turn, this growth was driven by OKKO and WOG, which accounted for 90 percent of the portfolio. Together with the Lithuanian volumes, PKN Orlen shipped 476,300 tons of gasoline to Ukraine in the year and secured its status as the undisputed leader (see Figure 4).

In Romania, OMV Petrom plays the role of Orlen, accounting for 92% of supplies from the country (283,000 tons). The same OKKO and WOG provided the flow. They were joined by AMIC Energy.

The aforementioned unfavorable gasoline market conditions created a difficult situation for OMV Petrom, which threatened to cause an outflow of customers to the north. According to available information, in 2025, the producer was forced to revise prices downwards and thus managed to stop OKKO and AMIC from taking flight. But WOG seems to have escaped.

Guten Tag!

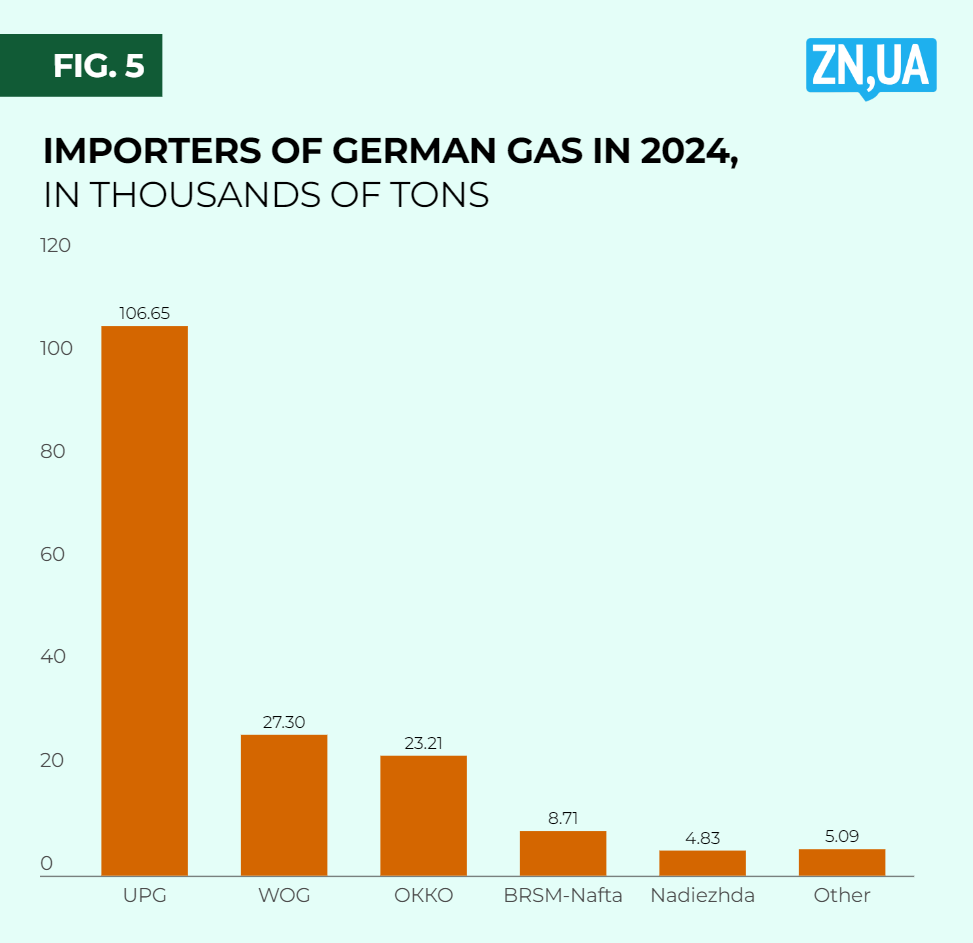

In 2021, it was no less inconceivable to imagine the supply of German gasoline to Ukraine than the import of American diesel. In 2024, it became commonplace. Germany soared from one gasoline tanker in 2023 to 175,800 tons in 2024, ranking fourth in the list of import sources.

The Polish holding Unimot was the first to pave the way at the former Rosneft refinery in Schwedt, but it was the UPG network that put the flow on a wide railroad track (in every sense of the word). It has become not only the largest supplier from Germany, but has also completely switched to this expensive but high-quality resource.

At the same time, the market discovered another German producer, Holborn Europa Raffinerie. The small plant turned out to be very friendly and flexible to Ukrainian counterparties, so both key players such as OKKO and WOG and regional chains and traders such as NADEZHDA, Martin Trade, etc. started working with it. Even BRSM-Nafta, which sells fuel of its own production at its gas stations, could not resist.

This year, the position of the Germans has every chance of strengthening (see Figure 5). The availability of the resource is expected to be improved by the aforementioned Unimot, which has developed a logistics scheme specifically for deliveries to Ukraine without storing gasoline at oil depots in Poland. As the saying goes, the ball is now in the Ukrainians’ court.

Hit the gas!

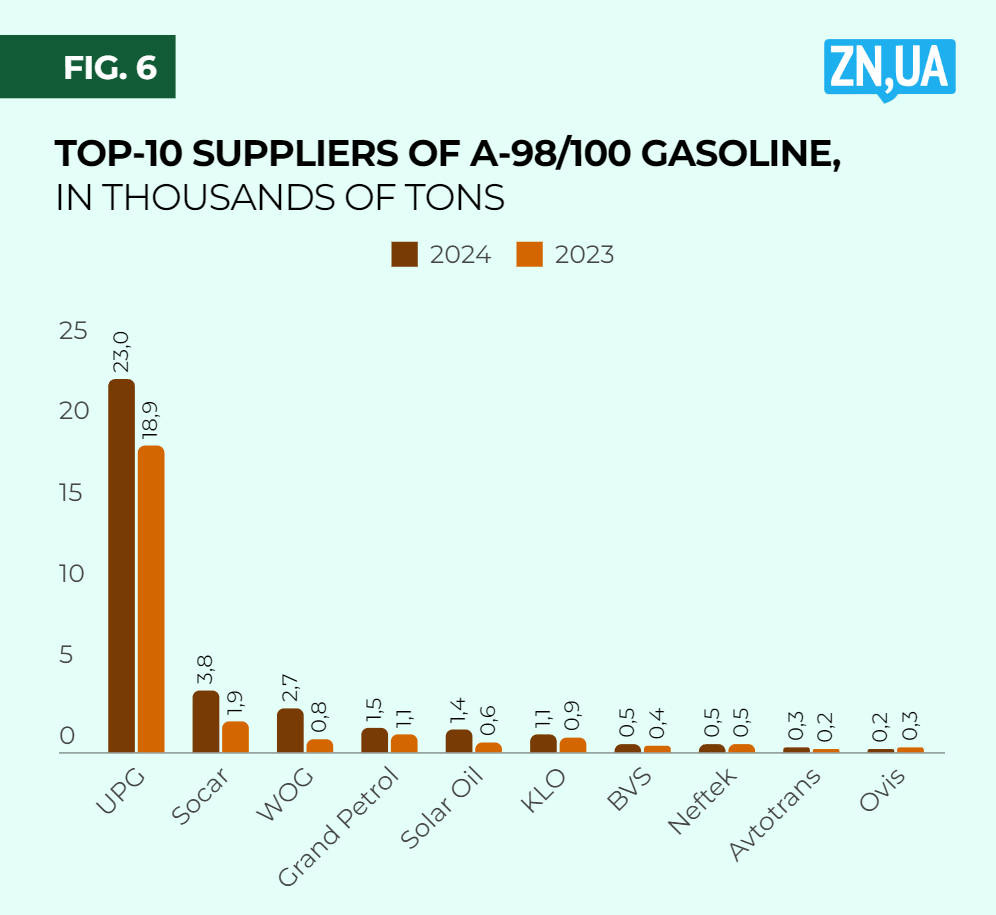

In 2024, imports of high-octane gasoline A-98/100 increased by 30 percent (36,400 tons). All the leading suppliers increased their imports (see Fig. 6).

UPG remains the leader, accounting for 63% of the total volume — 23,000 tons, which is 21 percent more than in 2023. Almost all of the volume was imported from Germany. UPG maintains the largest network for the sale of A-100 — more than 70 filling stations. It is followed by WOG with 56 filling stations and KLO with 29.

They were — and will be — importing

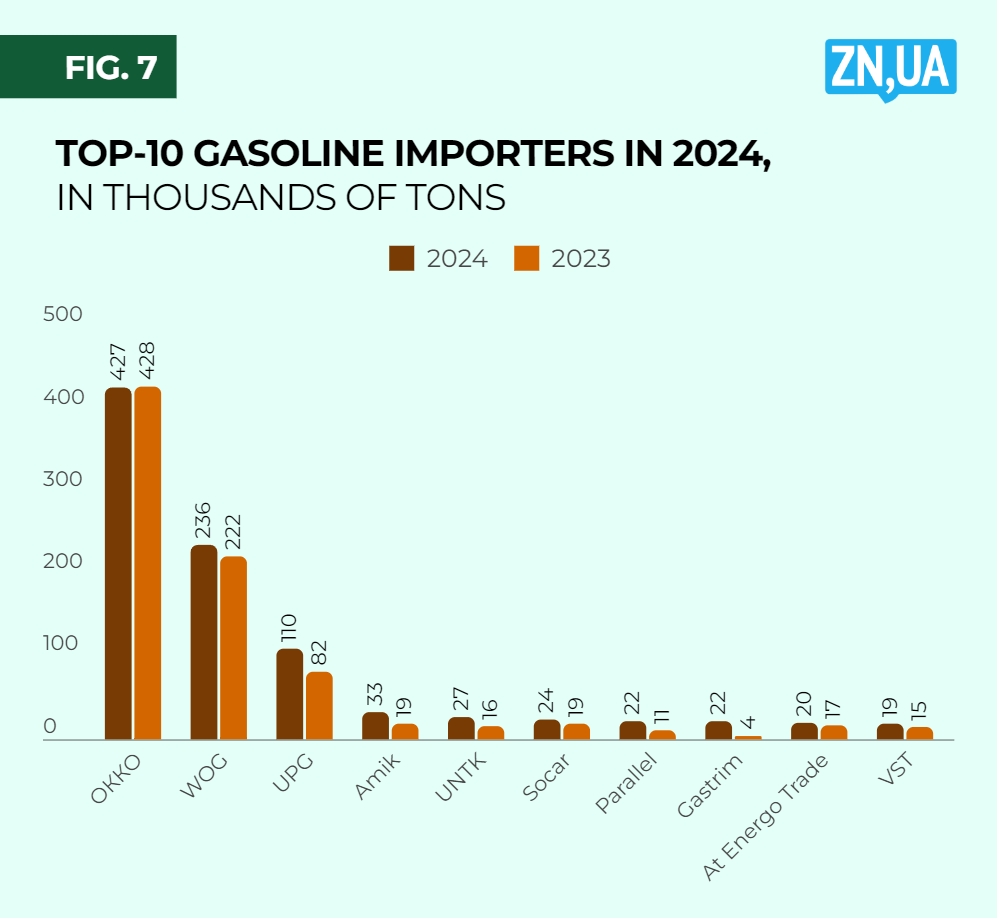

Over the past two years, the top three companies — OKKO, WOG and UPG — have imported 62% of total gasoline volumes (see Figure 7).

The largest seller of gasoline in the country, the OKKO network, has been strengthening its diversified supply structure in all areas. Poland, Lithuania, Romania, Germany — increased imports from these sources replaced the emergency supply from Greece in 2023.

WOG has traditionally followed the same directions, abandoning Greek gasoline in favor of Orlen’s plants and starting to import from Germany. The network’s difference is a gradual move away from Romania’s OMV Petrom, which, according to company sources, has become the most expensive in WOG’s basket.

UPG grew by 34 percent over the year, mainly due to stable wholesaling. The key for the chain was a marked change in logistics: the fuel went by rail after the company’s fuel tankers, which provided 100% of the chain’s imports, got stuck at the border in November 2023 due to a strike by Polish farmers.

The 72 percent increase in gasoline imports by AMIK Ukraine is primarily due to the transition to direct contracts with producers, whereas a year earlier the chain bought large volumes from other importers. But the sources have remained the same — Romania and Lithuania.

For the first time since 2021, a 100 percent wholesaler, UNTK, became one of the five largest gasoline importers, increasing its gasoline purchases by 71 percent (up to 26,800 tons) over the year.

The largest wholesale trader, JSC Energo Trade, increased its gasoline volumes by one third (20,400 tons).

Interestingly, UNTK and AT Energo Trade are among the largest importers of gasoline from Moldova (in fact, it is mostly Romanian gasoline).

The Parallel company doubled its gasoline imports to 22,200 tons. This leap was driven by the rapid and not fully clear growth of the Donetsk network. With 30 filling stations, mostly in the war-torn Donbas, last year it officially took over 70 MOTTO stations once owned by Eduard Stavytskyi. Since the fall of 2023, Parallel has also included the Prime network (more than 50 filling stations), which specializes in refueling trucks. It is also known to have purchased several small networks, including EDF and Luxwen. It is not clear where this financial inspiration came from.

There were also losses. Privat Group, BRSM-Nafta and Anvitrade left the top ten gasoline importers.

The first among them has actually defaulted since early January: some fuel brands began to disappear from gas stations back in October, and at the beginning of the year, Avias and ANP went out of business, leaving fuel coupon and card holders to deal with their problems alone.

In order to resolve the issue of fuel origin and quality, BRSM-Nafta started importing gasoline in the second half of the year. Over five months, 12,400 tons were imported, which is about a third of the network’s total sales for the period. However, the company has not yet been able to find passports for this gasoline at its filling stations.

How much did independence cost?

An important result of 2024 was the complete disappearance of unnecessary premiums that European fuel suppliers put in their prices. This was a classic market response to sudden demand from a new major consumer that had lost 100% of its petroleum product supplies as a result of the Russian attack in February 2022. At the peak in the spring of that year, markups sometimes amounted to 100% of the price.

Thanks to the crystallization of counterparties and the development of supply routes, the markups decreased and disappeared in 2024. For example, the pricing formula for Lithuanian gasoline returned to the 2021 model.

So, there is more than enough fuel, and all this without Russian or Belarusian resources. What is the price of true energy independence?

Yes, it is higher because of the longer distances. If the price of gasoline from the Mozyr Oil Refinery in Kyiv in 2021 was calculated using the formula “Northern European quotation plus $30 per ton (distance up to 300 km),” now Lithuanian gasoline travels 840 km from Mazeikiai to Yahotyn, Volyn and then 500 km to Kyiv. And this already costs +100 dollars per ton to the above quotation. That is, the difference is $70/t, or 2.2 UAH/l. This is 4%.

In other words, Belarusian gasoline would cost 55.8 UAH/l instead of 58 UAH. But at the same time, almost nothing has changed for Lviv consumers because the Belarusian resource was far away and the Lithuanian one is now closer than to any other region (except perhaps Volyn).

We can confidently predict that after the war is over, when Ukrainian oil refining is restored and seaports open, this difference with Russian-Belarusian fuel will decrease to 1–1.5 UAH/l. Was independence worth 2 UAH/l? This is a rhetorical question. As is the question of why the war was needed to give up buying Russian and Belarusian gas...

Please select it with the mouse and press Ctrl+Enter or Submit a bug

Login with Google

Login with Google