From Refugees To Investors. It's Time To Think About How To Bring Trillions of Dispersed Ukrainians’ Money Home

The forced migration of Ukrainians abroad during the full-scale war gave rise to the historical phenomenon of “scattered European Ukrainians.” Let's try to determine what the impact of this community on Ukraine's development might be.

According to EU statistics, the number of Ukrainians abroad during the full-scale war reached 4.3 million. But this is not the complete figure. Some Ukrainians are in Europe illegally; others have not registered as recipients of social welfare payments in their host countries. Thus, these groups are not on the radar of EU statistics.

According to various estimates, there may be about 5 million Ukrainians in the EU.

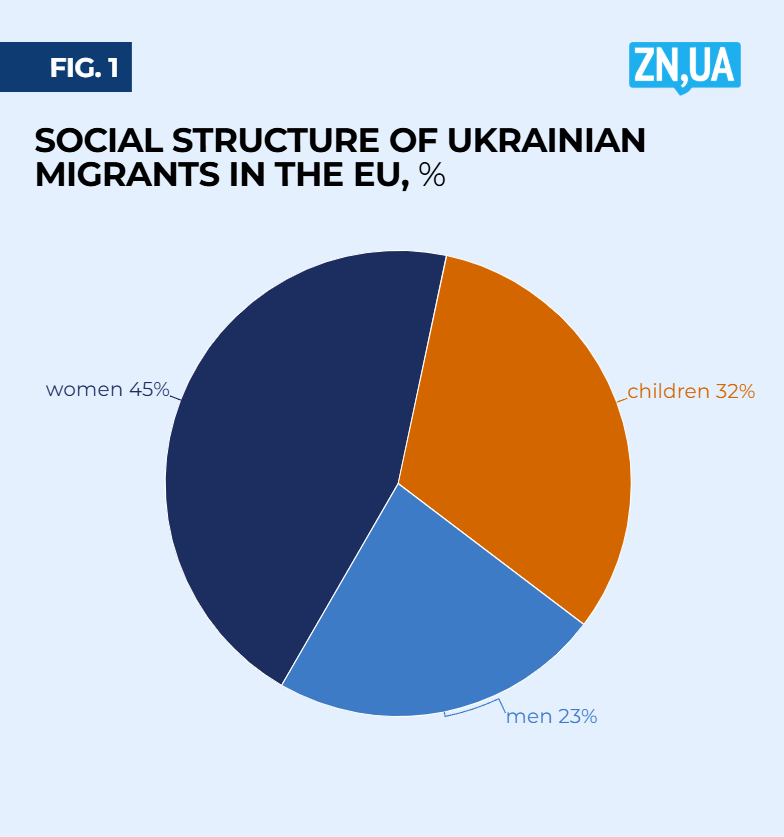

Their structure is as follows: 45 percent are women, 32 percent are children and 23 percent are men (see Figure 1). It can be assumed that there are significantly more men among the unrecorded refugee groups.

Some Ukrainian refugees are employed — about 1.6 million people or just over 37 percent.

At the same time, if we define such an indicator as per capita gross product, the employment factor is not decisive. As a rule, per capita GDP is defined as the result of dividing the total population by gross domestic product.

In the above formula, the population is understood to include all residents of the country: pensioners, children, the unemployed and the employed. This is primarily because the entire population participates in the formation of gross domestic product mainly through the process of consumption, as all social groups consume.

In addition, the number of Ukrainians employed in the European economy is constantly growing: in the first year of the war, there were no more than 10 percent of them. But children are growing up and are also included in the group of economically active population. If the war does not end soon, the number of Ukrainians employed in the EU will exceed 50 percent.

The NBU estimates that in 2025 the number of refugees from Ukraine to the EU may increase by another 500,000 people, with 25,500 such people recorded in January this year.

Finding themselves in a different economic frame of reference, one that is more efficient and capitalized, Ukrainians “suddenly” start to receive considerably higher income than they did at home, including social welfare payments, salaries and entrepreneurial income. Expenses are certainly also higher.

Moreover, within the framework of another economic matrix, the per capita gross product of Ukrainians instantly converges with the European average: moving from a country with a per capita GDP of $5,000 to a country with, for example, $40,000, a Ukrainian may not always become richer; however, he or she definitely becomes more capitalized as a social class, as a worker and as an entrepreneur.

Let's analyze these transformations.

Last year, Ukraine's GDP amounted to $188 billion. With a population of 30 million people (a rough estimate), this implies a per capita GDP of $6,300 (in 2021, with a population of 40 million and a GDP of $200 billion, this figure was lower, $5,000).

Now let's try to estimate a similar figure for Ukrainian communities in the EU.

Total GDP of Ukrainian refugees in EU countries

|

Country |

Ukrainian refugees, |

Per capita GDP of the country, |

Aggregate GDP of Ukrainian refugees, $ million |

|

Poland |

993 |

17,0 |

16,881,0 |

|

Germany |

1,170 |

44,0 |

51,480,0 |

|

Czech Republic |

395 |

20,0 |

7,900,0 |

|

Slovakia |

133 |

19,0 |

2,527,0 |

|

Romania |

181 |

12,4 |

2,244,4 |

|

Austria |

85 |

46,0 |

3,910,0 |

|

Spain |

230 |

28,5 |

6,555,0 |

|

Netherlands |

122 |

51,0 |

6,222,0 |

|

Ireland |

111 |

91,6 |

10,167,6 |

|

Norway |

80 |

79,0 |

6,320,0 |

|

Finland |

70 |

46,0 |

3,220,0 |

|

Sweden |

47 |

54,5 |

2,561,5 |

|

Lithuania |

48 |

18,6 |

892,8 |

|

Latvia |

48 |

16,7 |

801,6 |

|

Estonia |

36 |

20,0 |

720,0 |

|

Belgium |

88 |

44,7 |

3,933,6 |

|

Switzerland |

68 |

54,5 |

3,706,0 |

|

Total: |

3905 |

Х |

130,043.0 |

The table shows the number of Ukrainian refugees in the EU (the countries with the highest rates of migration from Ukraine during the war were analyzed). Most Ukrainians have moved to Poland and Germany in recent years — just under and over a million people, respectively. In other countries, communities of Ukrainian refugees ranging from several tens of thousands to several hundred thousand have emerged.

Per capita GDP in the EU countries is uneven: from $12,400 per year in Romania to almost $92,000 in Ireland. The calculation is based on nominal figures, not GDP at purchasing power parity.

The average level of per capita GDP in the EU is $44,600, and we are going to need this indicator.

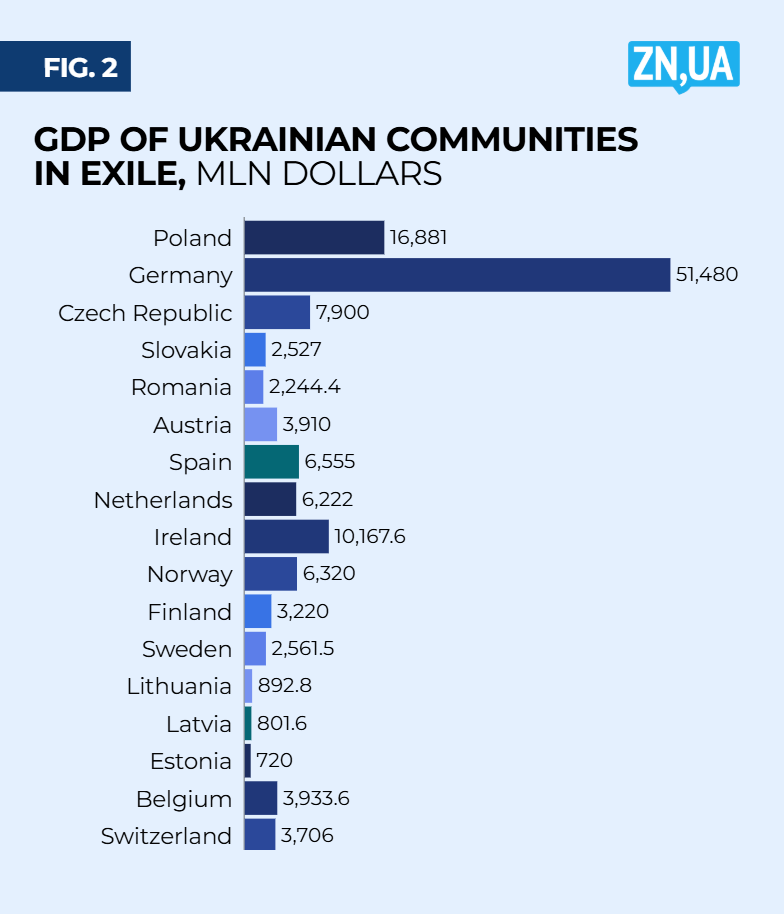

In each of the above countries, Ukrainian communities in exile generate a significant level of gross domestic product. Let's call it gross community product (GCP) (see Figure 2).

The largest GCP of Ukrainians is in Germany at almost $52 billion. This is quite natural: there are more than a million Ukrainian refugees in Germany, and the per capita gross product in this country is $44,000.

The GDP of Ukrainians in Poland ranks second at almost $17 billion.

Owing to the extremely high per capita gross product in Ireland, the GDP of Ukrainians in this country exceeds $10 billion.

In total, the group of countries listed in the table shows that the GDP of Ukrainians in the EU is $130 billion.

However, the list countries and the number of registered refugees from Ukraine are not exhaustive. The rest of the GCP for one million unrecorded Ukrainian refugees is calculated using the average per capita gross product of the EU at $44,600. This amounts to a GCP of approximately $45 billion.

Thus, the estimated GCP of Ukrainian refugees in the EU is $175 billion.

This is almost equal to Ukraine's GDP in 2024, $188 billion. But Ukraine is home to 28–30 million people, whereas this population simply goes to work and receives social welfare payments according to the standards of a less prosperous economy.

This telling fact suggests that in the near future, the Ukrainian community in exile in the EU will be equal in purchasing power to the domestic Ukrainian consumer market.

Sooner or later, this will cause a significant number of Ukrainian producers to penetrate this new market. Those who do so earlier will prevail over their competitors.

First of all, logistics and transportation will be developed, particularly the postal system, which serve as a horizontal connection between Ukrainians who stayed at home and those who went to the EU.

At the second stage, the demand of Ukrainian communities in the EU for certain Ukrainian products and even medicines will be met, as will be the demand for cultural projects, such as books for children, textbooks for self-education abroad, concerts and performances by Ukrainian artists.

Ukraine could create a whole new area of travel medicine, including dentistry, elective surgery, tests, preventive care, etc., aimed not at foreigners but at Ukrainians who moved abroad. So to speak, work in the EU and get your teeth treated at home.

But how to integrate the potential of the dispersed Ukrainians and channel it to the development of Ukraine in such a way that it would not just be a matter of humanitarian or philanthropic support, but would also be beneficial to the communities of Ukrainians in European exile?

Essentially, this requires launching the most convenient, simple and remote crowdfunding projects possible. This should be done on the platform of the maximum range of financial instruments: stock, including preferred stock, bonds, certificates of mutual venture funds, cryptocurrencies in the form of launching ICO projects — initial coin offering, i.e, “a type of attracting investment in new technology projects and startups in the form of issuing and selling new cryptocurrencies to investors.”

The maximum portfolio of strategic natural resources, economic assets and infrastructure facilities should be considered as projects. These can include mining of minerals, Ukrainian ports, railways, logistics, energy, including nuclear, the gas transportation system and underground gas storage facilities, etc.

Relatively speaking, there should be a dozen “icons” on the smartphone screen with the names of projects where scattered Ukrainians can invest from one hundred to thousands of euros or more in one click.

There is one anchor in this model, however: all these resources and assets are either managed by Ukrainian oligarch-owned financial industrial groups or are a coveted prize for international TNCs in the post-war period.

How to make the scattered Ukrainians and Ukrainians in the homeland at least minority shareholders of the national treasure? This is one of the most important conundrums of the country's development after the war.

Please select it with the mouse and press Ctrl+Enter or Submit a bug

Login with Google

Login with Google