Factors of (non)return: why do Ukrainians stay abroad during the war and may not return after it?

The forced migration of Ukrainian citizens abroad related to the full-scale invasion is one of the biggest negative damages that Russia has done to Ukraine, although not direct, but long-term. The departure of several million citizens of Ukraine (mostly young and economically active) will affect both the demographic portrait of the Ukrainian population and the economic capacity of Ukraine. Will they come back? And when will they want to come back? Under what conditions? To answer these questions, the Laboratory of Legislative Initiatives, with the support of the European Union, conducted a study of Ukrainian forced migrants. The quantitative survey was conducted by the research agency " Info Sapiens"*. We share the results of the study.

In general, the situation looks somewhat sad. And here's why. Most of the forcibly displaced people will not return. And the number of those immigrants who are younger will return even less. In addition, the situation worsens over time, and the state currently does not particularly plan to correct it. But let's look at it in more detail to better understand the situation.

Do forcibly displaced people plan to return home?

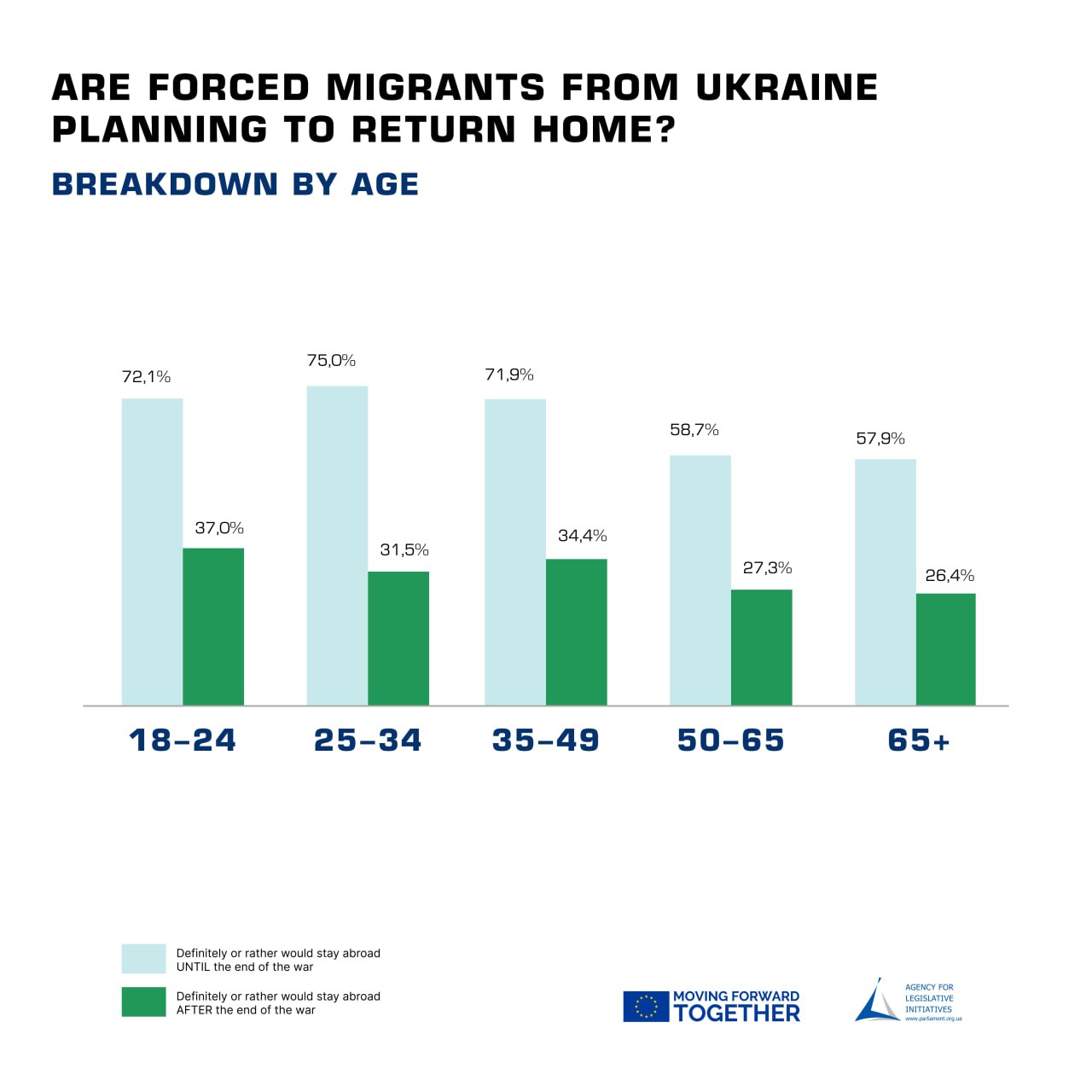

Let's start with the question of how many forcibly displaced people will return. To answer this question, we used a probability scale. Respondents were asked to rate the probability of their return from 0 to 100 points (0 – definitely not coming back, 100 – definitely coming back). Before the end of the war, only 30% of respondents gave more than 50 points (ie, the respondent is more likely to return), the average score is 33 points. This means that more than two-thirds of forced migrants are unlikely to return to Ukraine before the end of the war.

After the end of the war, the situation with the return of Ukrainian citizens to their homeland looks much better – 68% of respondents gave more than 50 points, the average score is 66 points. So, here the ratio is the opposite – two-thirds of forced migrants plan to return to Ukraine after the end of the war.

That is, a third of forced migrants do not plan to return at all, and the vast majority will not return in the foreseeable future. The age distribution is also quite disappointing – the younger the person, the less likely this person is to return.

If two-thirds (68%) of forced migrants are likely to plan to return to Ukraine after the end of the war, then it is important to understand what this means for them. In addition, it is worth defining what is meant by the concept of the end of the war? Answering the question "How will the war end?", half of the respondents (49%) are sure that Ukraine will reach the borders of 1991. Another 12% believe that Ukraine will reach the border of the controlled territory as of February 23, 2022. Perhaps this assessment is optimistic, but it also says something else. These people expect Ukraine to achieve rather ambitious goals and a significant military or diplomatic defeat of Russia. Therefore, another question arises that requires an unequivocal answer: will Ukraine be able to achieve such goals in the near future?

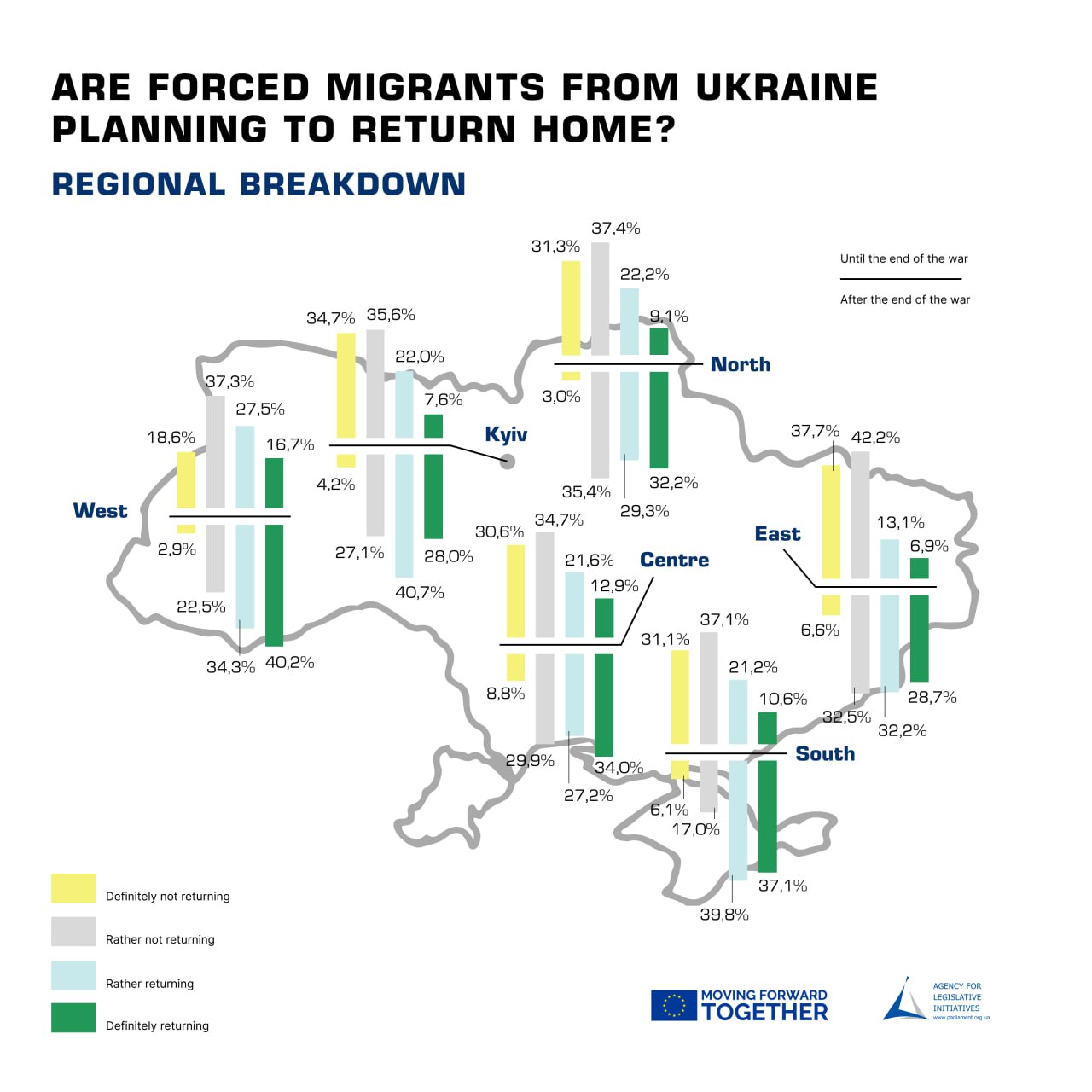

The regional dimension is also interesting – where forced migrants will return. The Laboratory of Legislative Initiatives study confirmed intuitive assumptions that residents of eastern and southern Ukraine are less inclined to return. However, even among those former residents of these regions who do plan to return to Ukraine, a significant part will probably change their place of residence, moving to another settlement, perhaps in another region. For example, for the eastern part of Ukraine, the share of those who definitely plan to return to their settlement is only 50% (for other regions it is 67–88%), while the other half is considering the possibility of returning to other settlements or does not know where to return at all.

Factors of (non)return of citizens

The study found strong factors that will influence the decision to (not) return – and safety is not always the most important of them. Quality of life matters most. Over time, forced migrants adapt to life abroad, get settled, socialize, get used to it. A telling indicator is living conditions: 44% of people rent a separate house or apartment, and another 20% of Ukrainians live in separate housing provided for free. That is, two thirds of forced migrants already have quite comfortable living conditions. And the ability to rent housing on your own is also an indicator of not the lowest level of financial support. For comparison, only 8.5% live in refugee shelters (the least comfortable housing option).

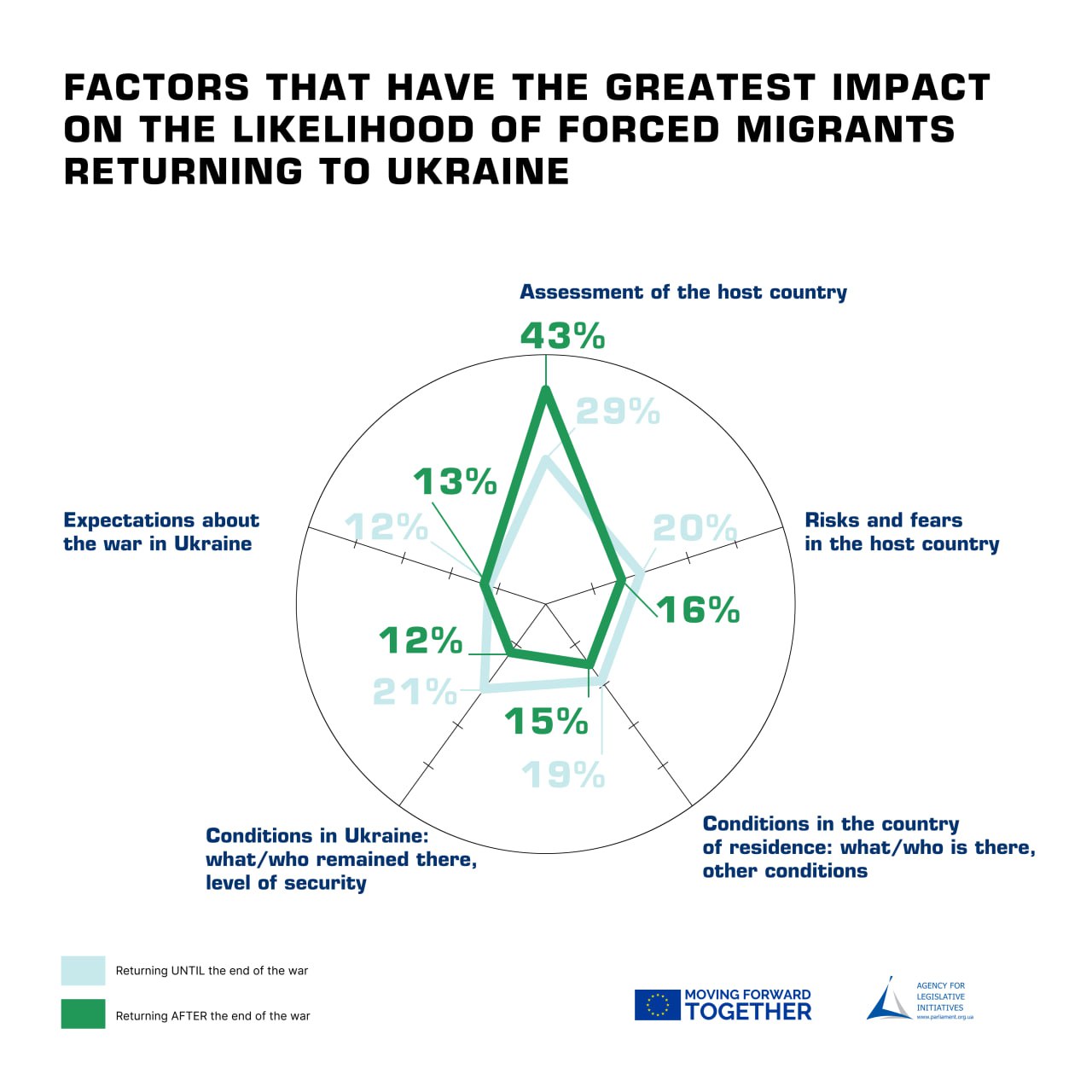

How forced migrants solved their housing problem is just one indicator, albeit a telling one. However, there are much more such indicators, they became the basis for econometric modeling, which made it possible to understand which of the factors are more and less important for the decision of forced migrants to return or not to return. These factors were combined into five groups.

The group of factors related to the assessment of the host country, that is, how satisfied the forced migrants are with the quality of life in the host country, turned out to be the most important. Starting from purely practical issues (for example, the quality of education, medicine, employment opportunities, the service sector, the quality of infrastructure, etc.) and ending with more general issues (for example, the closeness of the mentality of the population of the host country). It is this group of factors that determine 29% of the decision to return before the end of the war and 43% after the end (if we imagine the decision to return as 100%). Other groups range from 12 to 21%. Moreover, the most important reason that reduces the desire to return is the expectation of a low quality of life in Ukraine. It is worth noting that 60% of respondents indicated this reason.

Instead, security considerations turned out to be more important when deciding to leave Ukraine – 79% of forced migrants indicated at least one security reason for leaving abroad. In other words, migrants left because of the danger, but do not return because of the quality of life.

And what about the state?

The problem of mass migration abroad could be at least smaller. The study showed that 38% of forced migrants considered the option of staying in Ukraine in safer regions. If we count from 6 million forced migrants, about 2.3 million could remain in Ukraine, receiving the status (at least for a while) of internally displaced persons IDPs.

The conditional form of these sentences leads to another problem – the state did not take active actions to ensure that more people remained in Ukraine, and even after their departure, Ukraine did not formulate a policy for the return of forced migrants. There is no strategy for the return of forced migrants and no clearly defined body that should deal with it. Various data and guesses about the number of forced migrants circulate in the public space. That is, there is not even approximately accurate information about how many forcibly displaced people there are and where they are.

Undoubtedly, the return of forced migrants is a challenge for Ukraine. The number of migrants who will return and the timing of their return affect Ukraine's ability to effectively mobilize domestic resources to wage war and the quality of post-war reconstruction. The "natural" dynamics of migrants' behavior does not favor their return. If the statesmen do not continue to implement measures to return Ukrainians to their homeland, Ukrainian citizens will continue to arrange their lives abroad, adapt, get used to it, and the chances of their return will decrease and decrease. The number of Ukrainians who will still return seems quite limited. Changing such a situation requires intervention – a set of measures aimed at changing the current situation. Apparently, the only one who has enough legitimacy and organizational capacity for such an intervention is the state.

* In July 2023, 1,032 Ukrainians over the age of 18 were interviewed. The survey method is sending SMS messages to the numbers of Ukrainians living abroad. The sample represents Kyivstar and Vodafone users who went abroad after February 24, 2022, by country of residence, with the exception of Russia and Belarus. The sample was stratified by market share of each mobile operator and by country according to the latest available data obtained from the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Within each country, mobile numbers were randomly selected for the survey. The theoretical margin of sampling error is +/-3%.

Please select it with the mouse and press Ctrl+Enter or Submit a bug

Login with Google

Login with Google