WHY RUSSIA AND UKRAINE ARE NOT AND HAVE NEVER BEEN FRATERNAL PEOPLES

article by MARYNA STARODUBSKA, Managing partner of TLFRD consulting company, adjunct professor of Kyiv-Mohyla Business School (kmbs)

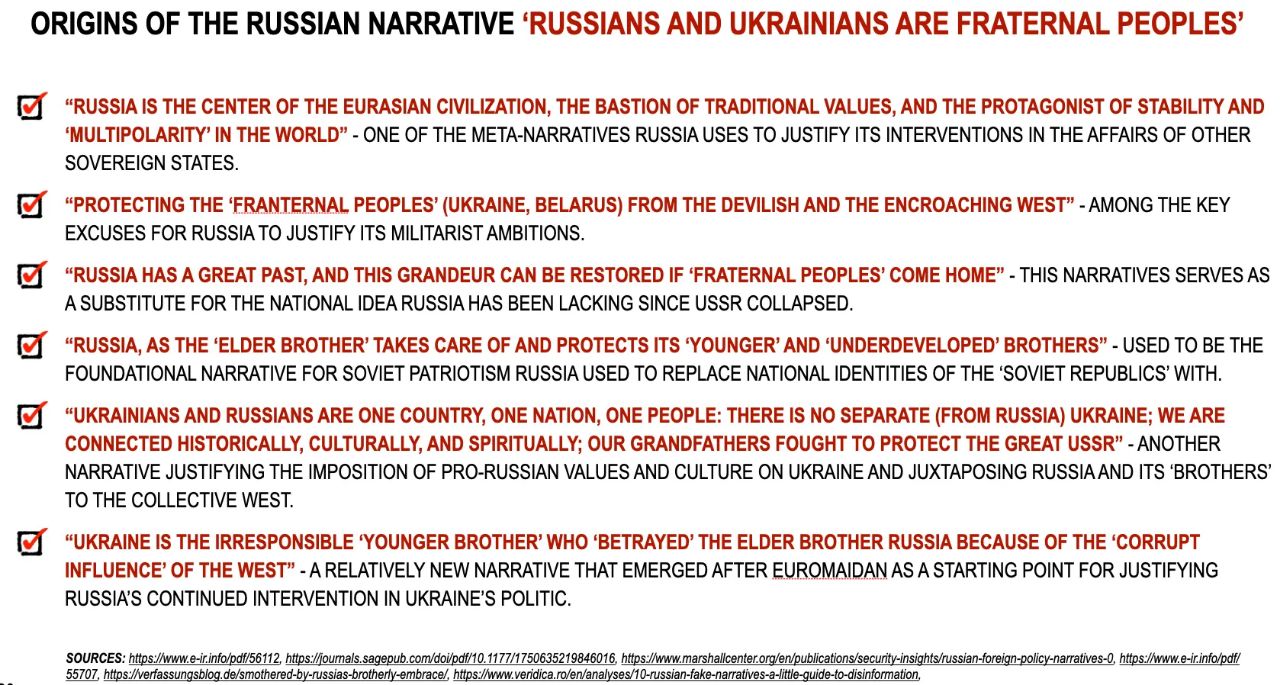

Perhaps no Russian-created myth about Ukraine remains as deeply ingrained in our collective world-view as “Ukrainians and Russians are fraternal peoples”. Several generations of Ukrainians and Russians have grown up convinced they have historic similarities that were never really there. However, all statements concerning “fraternal peoples” are propaganda, aimed at the countries Russia considers to be within its “area of influence” and has been unsuccessfully trying to “return home”—where they will be under its control, that is. Analyses of similarities and differences between peoples can be carried out in several academic fields: from history to anthropology to cross-cultural studies, which is where we will look for evidence of differences between Russians and Ukrainians.

As the levee steers the river, or how culture shapes and cements a country’s institutions

Despite the effects of globalization and international economic cooperation, ~50% of variation in national cultural orientations is unique to each country. National culture takes shape over the course of centuries, under the influence of the country’s landscape, climate, location, wars and ruling regimes, societal interaction and stratification, and is strongly resistant to change.

It is the national culture that shapes institutions—through which social choices are made, political influence is distributed, and an enduring regularity of behavior is ensured: rules, laws, self-regulation, codes of ethics and conduct, conventions, embedded social norms. After the institutions have developed, they further ‘steer’ national culture—as the levee steers and contains the river.

For the national culture to shift, change must happen on its deepest level—where our “underlying assumptions” lie, the collective worldview templates that society reproduces “by default” from generation to generation, which can take ~100 years to change.

Among the underlying assumptions for Ukrainians is the existence of free will [volya] (making important decisions without pressure or coercion) and the flexible and non-mandatory nature of rules (human relationships are more important than rules and unforeseen circumstances can make the rules irrelevant). In contrast, among the underlying assumptions for Russians is a lack of agency to make decisions and change one's life (“what can I do?”, “they [upstairs] know better where to go and what to do”) and violence as a means to ensure obedience and deference.

The next level of national culture manifestation contains “beliefs and values”, core principles that “signal” how one should interact with their environment in specific situations. These can take ~10 years to change, but the shift will not be radical, usually following the path established by underlying assumptions.

For example, after the collapse of the USSR, Russia completely lost any remnants of their national idea (maintaining the country’s “grandeur” by subduing other countries). The country has been compulsively trying to 'make itself great again' since then by “saving the Russian-speaking people” in the adjacent countries it considers “younger brothers” who need to “return home”. In contrast, Ukrainian culture has a deeply embedded contempt towards anything authoritarian, and its national idea (albeit not formalized or legitimized via public nation-wide discussions) revolves around the existence of free will [volya], agency, and a lack of external coercion.

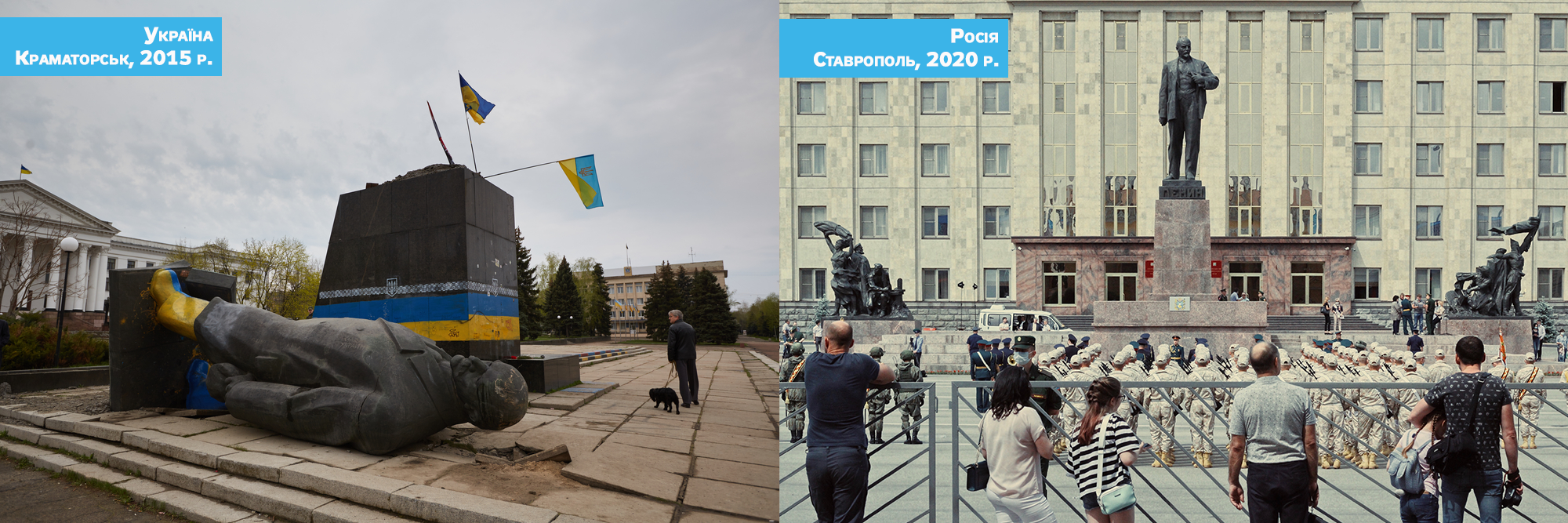

The most obvious level of national culture is “behavior and artifacts”—the expectations, norms, and symbols that signify the (un)desired formats of societal interactions and can change in ~2-3 years. While these are the most prone to change, that change is usually non-fundamental. Consider that Russia is among the most atomized (disconnected) societies in the world, where a citizen is, in fact, a “subject” whose behavior is determined by the decisions made “upstairs” without their participation. This is why a country with a population of 140-million hasn’t had any meaningful protest activity in the last 20 years, while Ukraine has had two revolutions during the same period of time.

InfoSapiens research shows that 66% of Russians support the “special operation” in Ukraine, 71% feel it’s is fair, 69% feel pride, and only 12% feel ashamed. While 30% of Russians believe ‘Russia should stop the “special operation”, only 19% said they would stop the “special operation” if this decision was theirs to make. There we have the “someone, but not me, should do something” attitude—where there is no agency, only helplessness.

Cubic watermelon or ‘I have my washing machine, my summer house is renovated, now where’s my empire?”

If Russia and Ukraine are so different, then why do several flagship systems analyzing national cultures (Hofstede, GLOBE, Trompenaars, Inglehart, Hall) show these two countries having similar cultural dimensions and areas of value developments? A metaphorical answer to this complex question can be found in the way Japanese farmers grow watermelons that are convenient to store and transport—by putting them in cubic baskets so that they take on a cubic shape while ripening.

What does national culture have to do with cubic watermelons? The institutions shaped by a country’s culture define it’s ability to evolve. If the country’s institutions are effective, legitimate, society-oriented, have checks and balances, and do not contradict social norms, they will “steer” the same beliefs and values into a different direction than they would had those institutions been punitive, corrupt, unreliable, and alien to a society’s norms.

Both Russia and Ukraine are collectivist (belonging to a like-minded “in” group that supports you); have high levels of uncertainty avoidance (changes and everything unknown = stress, knowing “what happens tomorrow” is paramount) and high power distance (where less powerful members of organizations and institutions accept and expect unequal power distributions as demonstrated through status). However, the differences between the two nations lie in how similar cultural dimensions are institutionally “programmed” and manifest on societal and individual levels.

DIFFERENCE #1. Ukraine is a democracy with disdain for autocracy, while Russia is an autocracy with disdain for democracy.

Russia is an authoritarian state (personalist dictatorship) lacking any significant periods of democratic rule throughout its history, or any interest in it’s norms. Studies show that only ~12.5% of such dictators lose power quickly, and usually this occurs through death or coup. For Russia, democracy is an irrelevant and dangerous regime because it encourages autonomous thinking by the wider population and complicates control through pressure.

For Russians, it’s not only important to differentiate from others through status, but also to coercively dominate over those on the lower levels of the hierarchy, in order to demonstrate a level of influence that then grants access to interact with people of comparable status. In such a culture, sacrificing one’s interests for the “in” group interests is expected by default. Representatives of “out” groups in a society like this are “alien” and, therefore, “enemies”.

Ukraine, on the contrary, has never been prone to authoritarianism. It hasn’t existed long enough within the same borders, and while it has had several generations of similar rulers, it hasn’t developed embedded approaches to statehood of any kind, let alone authoritarian ones. Even when it was a part of the USSR, regionalism in Ukraine was stronger than centralization.

For Ukrainians, it is important to be successful and differentiate from others through status, but their focus is on protecting one’s interests first. Simultaneously, it’s important for Ukrainians to peacefully coexist and synchronize their own goals with the “in” group, as belonging to such a group and having relationships within the group improve the quality of life. Yet sacrificing one’s interests for those of the “in” group is not a “default” expectation but a conscious choice. Representatives of “out” groups in a society like this are “alien”, but are not necessarily “enemies”.

DIFFERENCE #2. Russian and Ukrainian collectivism are not the same.

Though both Russian and Ukrainian societies are collectivist, their types of collectivism are not the same. The types of individualism are also different. Collectivism and individualism can be “vertical”—where societal relations are based on competition, status determines authority and value, and there is an inclination to pressure and coercion rather than dialogue; and/or “horizontal”—where societal relations are based on everyone’s uniqueness without pursuing status, there is dialogue rather than pressure, and authority is gained via leader’s acceptance by their followers, instead of coercion.

Ukraine historically has been a vertically collectivist society, due to their high power distance, a relatively conservative and hierarchical orthodox religious foundation, and high uncertainty avoidance that caused a heightened need to control “what happens tomorrow” and to always “save for a rainy day”. However, due to the absence of the “automatic-obedience-under-pressure” norm, Ukrainians have been able to “overthrow” their illegitimate ruler or productively function without one through horizontal connections and informal agreements. And due to its intolerance of authoritarianism, coupled with having been conquered by culturally different aggressors and its traditions of local self-organization, Ukraine’s historically developed vertical collectivism is balanced by a horizontal one. Moreover, there is a quite pronounced vertical individualism “mixed” into our culture: the freedom to be able to focus on one’s own interests within the legitimately led ‘in”-group is important.

Russia has invariably been a vertically collectivist country, dominated by this specific type of collectivism. The need for a “tsar-omniscient-idol-like” ruler, to whom the “subordinates” of the state’s hierarchy delegate the adoption of all significant decisions is deeply embedded in its authoritarian legacy. Any “horizontal” practices are discouraged and punished: autonomy, critical thinking, realizing the consequences of one’s actions, etc. Consequently, negotiations, upholding agreements, open information exchange, and other instruments of non-coercive interaction are alien to the Russians and are considered signs of “weak”, unstable regimes and unreliable people. Individualism in such a society manifests predominantly only on the highest levels of the societal hierarchies – one has to “fight” for the right to focus on one’s interests by dominating over others.

DIFFERENCE #3. The role and nature of institutions and their developmental legacy in Ukraine and Russia are different.

Ukraine historically has had weak and unstable formal institutions, which, during periods of conquest, functioned punitively and changed frequently. Consequently, the informal institutions (“networks of reliable people”) have had more longevity, serving as insurance in case the formal institutions failed to perform their functions. “An acquaintance” received assistance and information easier and quicker, and the problems of someone who had not “just walked in off the street” received more attention. By the way, online interactions is one of the ways to identify the “in” group by non-institutional factors (whether one moved abroad or stayed, posts photos “from life” or not, volunteers or “just” tends to the needs of family, are all examples).

Russia, as a former empire with a legacy of punitive, self-preservation-focused institutions and the embedded norm of suppressing the autonomous thinking and civil will of its wider masses, has no tangible signs of horizontal interaction. In such a culture, hierarchy is the only possible format for functioning social systems, since the population’s ability to think critically and its agency to make decisions without coercion are rather low.

Another way that Russian culture differs from Ukrainian and most European cultures is the coexistence of trust and control in superior-subordinate relations. In most European cultures (including Ukraine), the higher a superior’s trust in their subordinate is, the lower the degree of implied control (trust and control are mutually exclusive states). In Russian culture, any trust the superior has for the subordinate is impossible without control, which the latter expects no less than the former, thus avoiding any personal responsibility: “do not protest”, “do not stick your neck out”, “give the order to cease resistance”, “sit out the difficult times”.

As we have seen, even similar dimensions of national cultures can manifest differently in societal interactions, values, communications, and behaviors, depending on the way formal and informal institutions in the country have developed. In Ukraine and Russia, the paths, the form, and the role of the institutions are different. As years go by, the dissimilarity between Russians and Ukrainians will become increasingly obvious.

Read this article by Maryna Starodubska in russian and Ukrainian at the links.

Please select it with the mouse and press Ctrl+Enter or Submit a bug

Login with Google

Login with Google