Quarter of Working People Have Enough Money Only For Food. Indeed, Why Not Raise Their Taxes?

Whether Ukrainians have a margin of safety sufficient to raise taxes is an important social and economic issue.

The main driver of our economic development is demand. No matter how much grain we sell to Africa or oil to Asia, the vast majority of Ukrainian businesses live and survive thanks to domestic consumers. Therefore, the financial stability of Ukrainians is one of the few reliable indicators that the economy will survive.

That is why ZN.UA, with the help of the Razumkov Centre, asked our fellow citizens several questions about their financial situation. The results came synchronously with the government’s decision to raise taxes for citizens.

Well, let us see if there is something to shear from our flock.

ZN.UA note. On July 18, the Ukrainian government approved a bill amending the state budget and the Tax Code to increase this year’s budget expenditure by UAH 500 billion. One of the sources of additional funding proposed by the government is a tax increase, which should bring UAH 125 billion to the budget by the end of this year alone. The government’s updated proposal calls for a significant expansion of the military tax base and an increase in the tax rate, in particular from 1.5% to 5% for individuals.

The introduction of the military tax for all categories of taxpayers is a logical and long-awaited decision. It is difficult to find arguments why some pay this fee and others do not. Instead, raising the rate from 1.5% to 5% for individuals deserves at least a cursory analysis of the risks and benefits of this decision.

An example to understand the scale: an employee currently receives UAH 14,500, which means that his salary is equal to UAH 18,000, and the military tax of 1.5% is UAH 270. If the rate is increased to 5%, instead of 270, we get 900 UAH for each officially employed worker. Such significant changes cannot but affect the amount of money on hand, as labor costs are traditionally the largest item of production costs and the first item of savings.

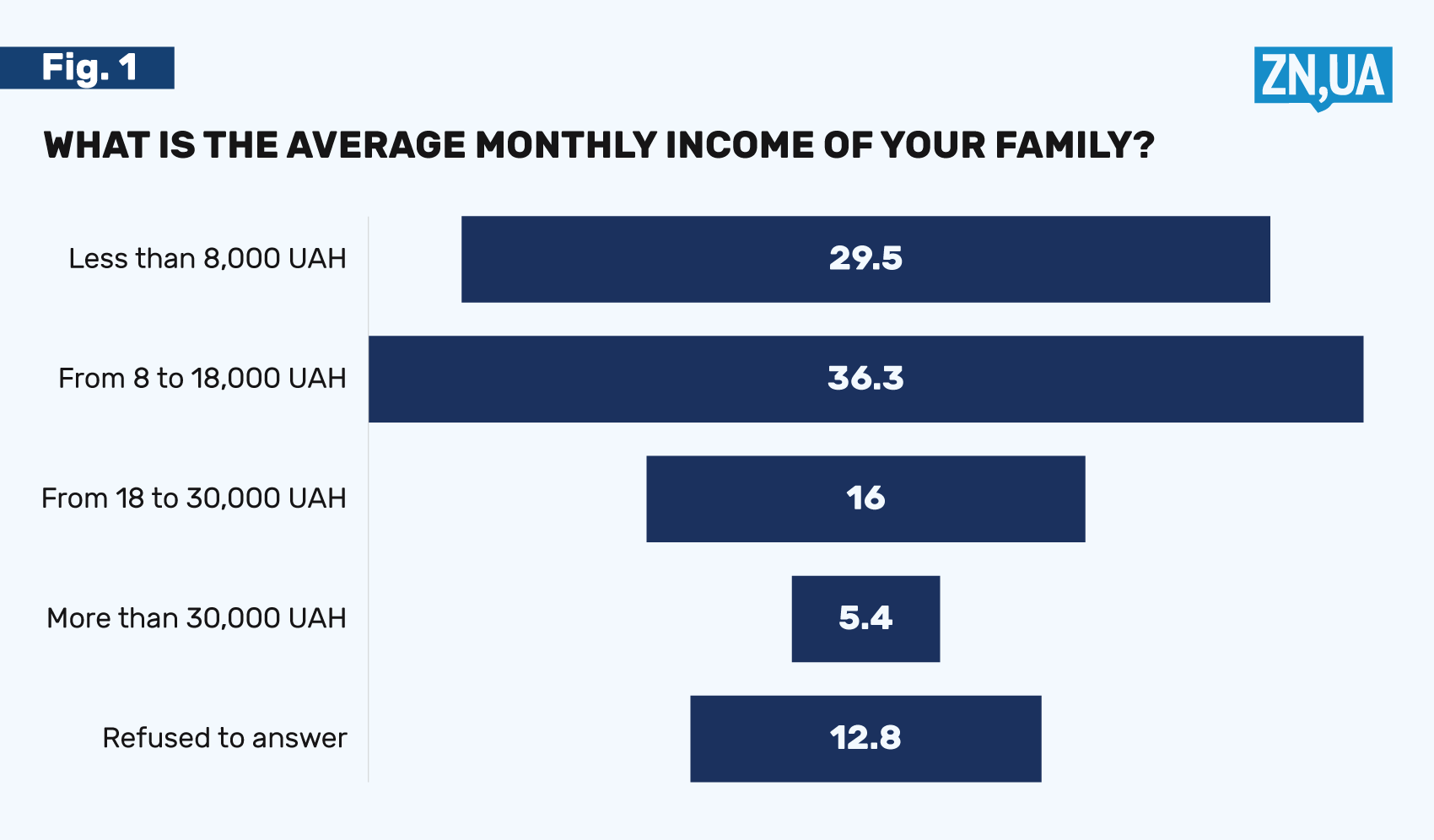

In response to the question “What is the average monthly income of your family?” 29.5% of respondents chose the option “Less than 8,000 UAH,” 36.3% chose “From 8 to 18,000 UAH,” 16% said “From UAH 18 to 30,000 UAH,” and only 5.4% receive more than 30,000 UAH monthly (see Figure 1).

It should be noted that the question was about family income, i.e., aggregate income, and thus the answers look rather pessimistic. We can only hope that the 12.8% who refused to answer this question are actually underground dollar millionaires.

Of course, the lion’s share (67.2%) of those who live on less than UAH 8,000 are unemployed either because of age or health reasons. But working respondents are not living their best lives either: 43.6% of them chose the option “from 8 to 18,000 UAH,” and almost 22% can boast of incomes in the range “from 18 to 30,000 UAH."

Regionally, the picture is more or less homogeneous. The only thing that catches the eye is the high level of inequality in the east. While the number of families with an average monthly income of up to 8,000 UAH is higher than in Ukraine as a whole (35% vs. 29.5%), the highest percentage of families with an income in the range of 18 to 30,000 UAH (20.3% vs. 16% in Ukraine) and with an income above 30,000 UAH (8.3% vs. 5.4% in Ukraine as a whole) is recorded there.

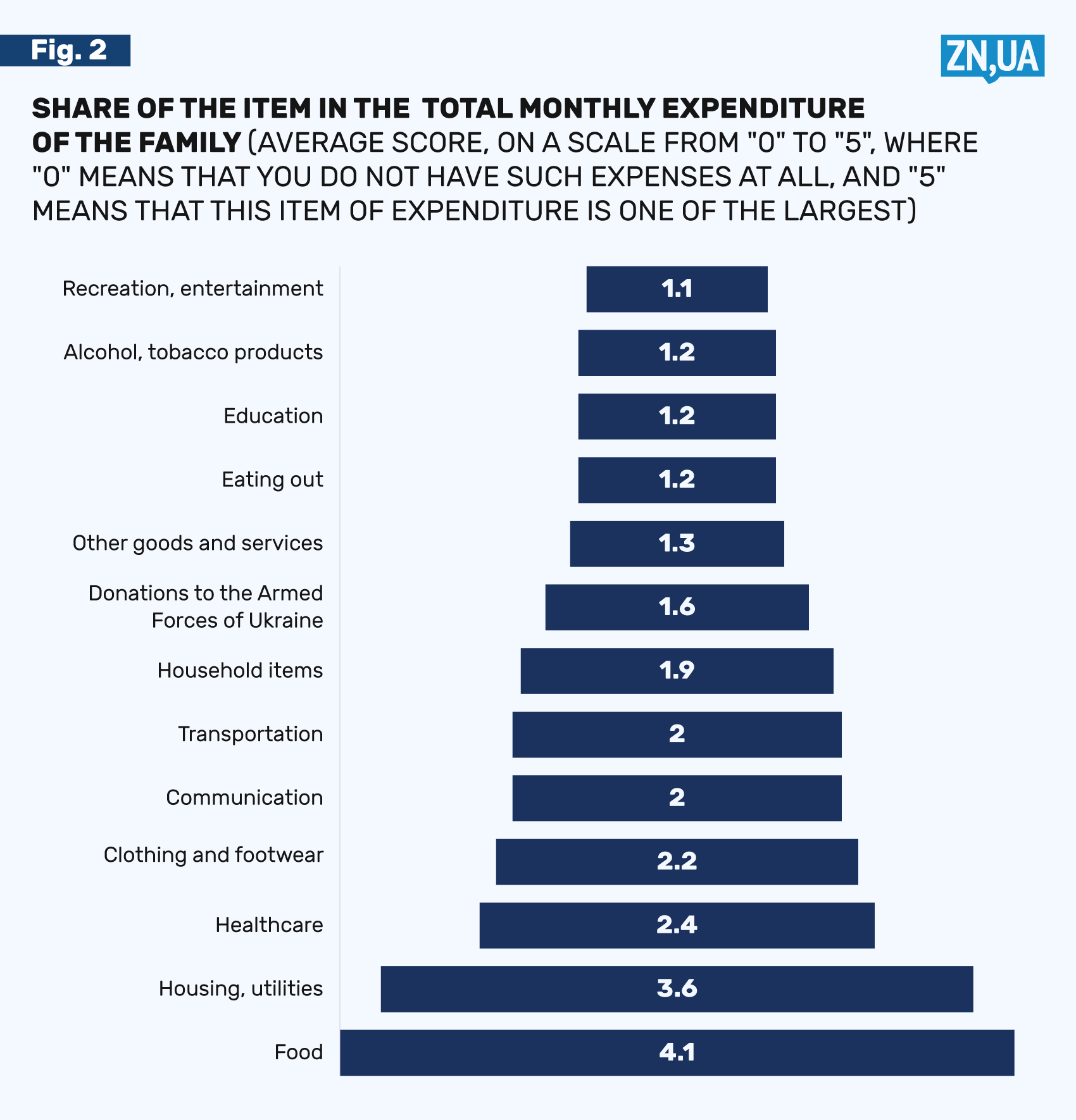

What do Ukrainian families spend their money on? We asked respondents to rank the most common expenses by the share they make up in the family budget (on a scale from “0” to “5,” where “0” means that there are no such expenses at all, and “5” means that this item of expenditure is one of the largest). Figure 2 shows the average scores that the expenses received.

No one will remember the former Minister of Social Policy Andrii Reva, but everyone will remember his phrase: “Ukrainians spend half of their earnings on groceries not because they earn little, but because they eat a lot.”

Well, unfortunately, Ukrainians still eat a lot. And judging by the fact that the next largest item of family expenses is housing and communal services, they also shower a lot.

In fact, the priority of expenditures is survivalist: food (4.1 points), utilities (3.6 points), healthcare (2.4 points), clothing and footwear (2.2 points), transportation and communication (2 points each), household items (1.9 points), other goods and services (1.3 points), eating out, alcohol & tobacco products, and education (1.2 points each), and recreation & entertainment (1.1 points).

It's nice to see that donations to the Armed Forces outranked most “optional” expenses (1.6 points). But let’s remember that this is a survey in which sociologists cannot “filter out” the respondent’s desire to look better than they really are.

Well, according to Eurostat, the distribution of household expenditures in the EU countries is different. Housing and utilities are in the first place with a significant margin — up to a quarter of all expenditures, followed by food (about 13%) and transportation (12.5%), then miscellaneous goods and services, entertainment/culture, eating out and hotels (each category at 10%), and only then clothing and footwear, health and communications (none of which gains even 5%).

Of course, this doesn’t mean that while “Ukrainians eat a lot,” Europeans have fun and travel. But it still means that our income is still only enough to cover basic expenses, and we finance everything else, as our Ministry of Finance likes to say, on a residual basis.

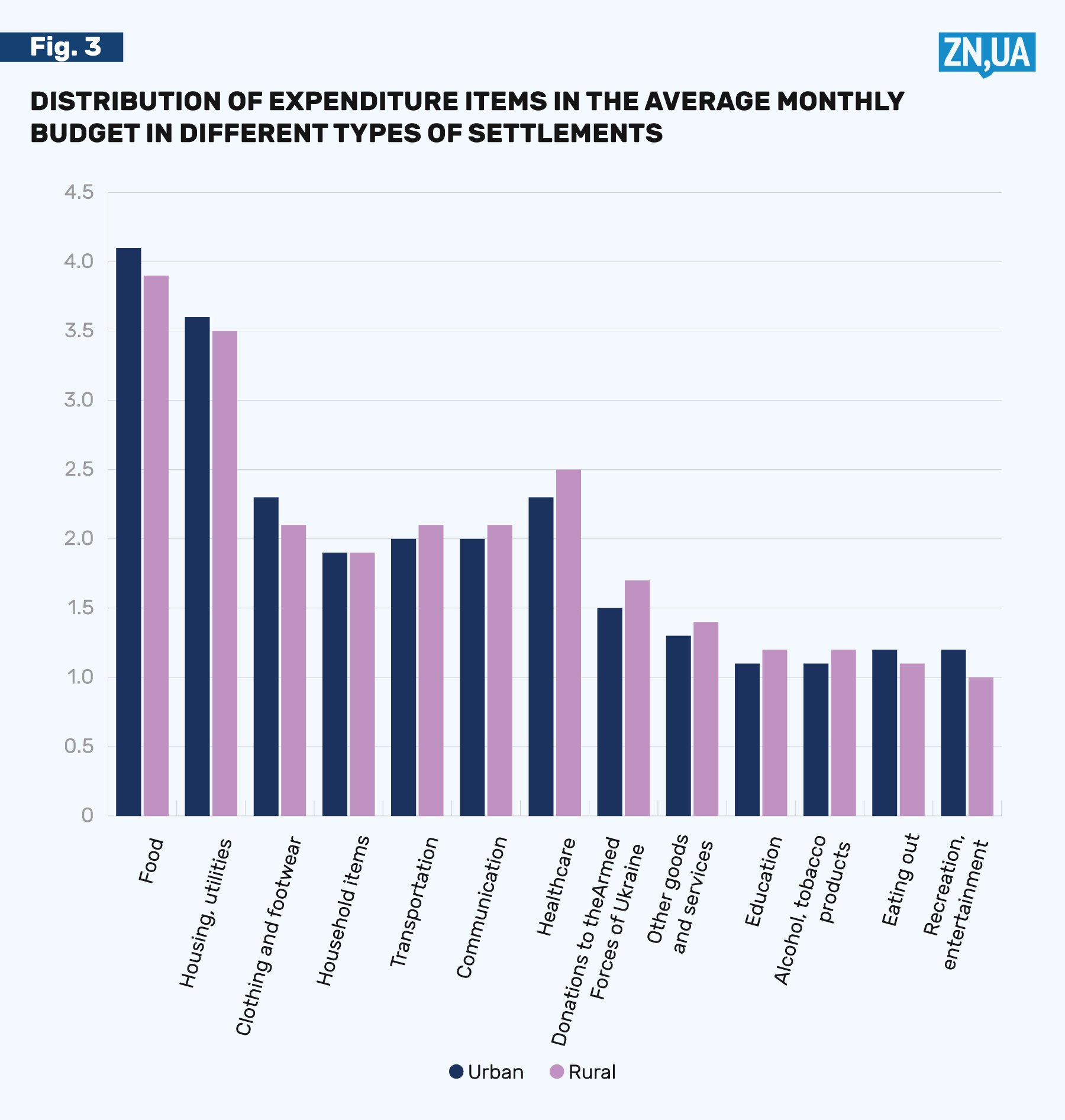

One can see that the issue is the sufficiency of money, and not the availability of certain “extras,” by looking at how similarly urban and rural residents answered this question (see Figure 3). Despite the officially recorded theater boom, record profits of book publishers, and “full houses” in Kyiv restaurants, most Ukrainians continue to spend the lion’s share of their money on the essentials, both in cities, where there are plenty of opportunities to squander money, and in villages, where there are fewer.

Determining the level of well-being is a difficult exercise; for some people, a cottage is a castle, while for others, a six-figure bank account is poverty. That is why self-assessment of well-being is the best indicator available.

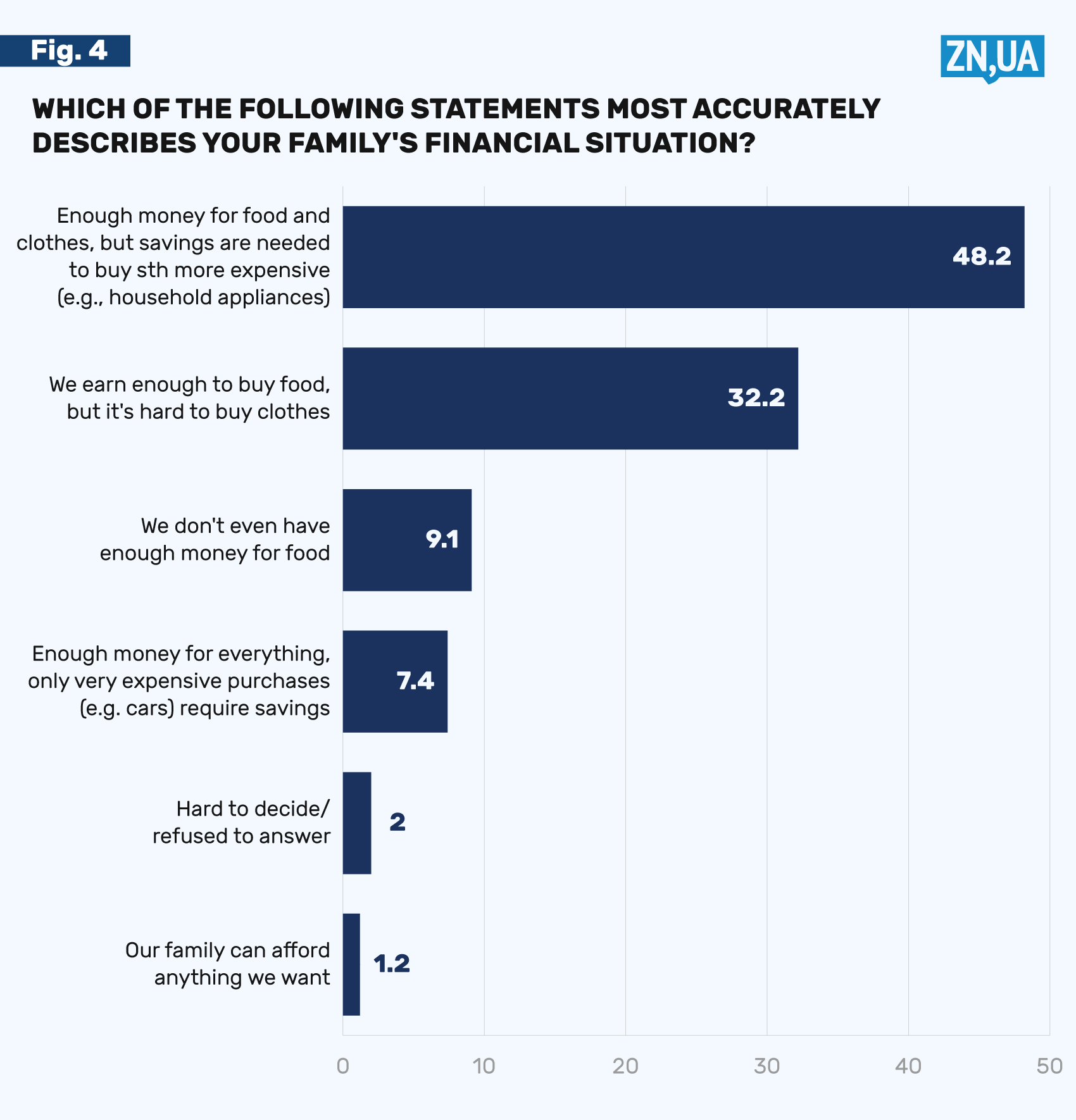

In response to the question “Which of the following statements most accurately describes your family’s financial situation?” (see Figure 4), more than 48% chose the option “We have enough money for food and clothes, but savings are needed to buy something more expensive (e.g., household appliances).” Slightly more than 32% answered that “We have enough money for food, but it is difficult to buy clothes”; 9% chose “We do not have enough money even for food”; 7.4% said that they have “Enough money for everything, only very expensive purchases (e.g., a car) require savings.” Only slightly more than 1% said that their family can afford whatever they want.

Yes, we remember that Ukrainians are not braggarts and would rather be poor, but 9% of families that do not have enough money even for food, as well as 32% that have enough for food only, is a very sad result.

Well, both the current level of Ukrainian income and its distribution, with a significant predominance of basic expenditures, consistently feed only the same basic sectors of the economy, such as food production. That is, all “non-basic” areas will face insufficient demand to one degree or another. Given a choice between producing corn flakes and children’s building sets, most people will choose the flakes because demand for them is guaranteed. And the desperate people who choose the building set will definitely put in many times more effort to maintain their business than the food producers.

After all, the “invisible hand of the market” always distorts economic development in the direction of demand, and if demand is limited to basic expenditures, the economy will be just as “basic,” with a very limited number of highly competitive niches. This is hardly the economy of anyone’s dreams.

It would be even worse if this already limited and distorted consumer demand were to be reduced by additional taxation of household income.

According to the June Financial Stability Report, which is regularly prepared by the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU), real household incomes are growing significantly: “The average monthly wage in the first quarter of 2024 increased by 22.5% compared to the same period of the previous year. A gradual increase in the minimum wage at the beginning of the year and in April, an increase in public sector payments, a 10% year-on-year increase in military pay and the indexation of pension payments have a positive impact on the overall level of income.” The NBU believes that a significant slowdown in inflation is an additional factor contributing to the growth of real incomes.

All this optimism also applies to the people we surveyed (at least our survey took place after the NBU report was published). So, we got rather depressing results, including 41% of families that are literally surviving, after raises, increases and indexations. Of course, the situation is better for those who are employed, where only a quarter of families (25.2%) have enough money for food. The majority (56.9%) can afford food and clothing, and have to save for something more expensive. This is a very dubious achievement. So, the decision to increase taxation of employees is hardly optimal.

You might say it was forced? Perhaps. But then why doesn’t it go hand in hand with forced spending cuts, forced cover-ups of corruption schemes, forced struggles against irrational or simply inappropriate procurement?

Somehow, one cannot speak of the need to raise taxes for the population when the budget loses about $1 billion annually from the shadow tobacco market alone, when the Ministry of Energy plans to bury $5 billion in flooded Khmelnytska Nuclear Power Plant units, when exporters simply have not returned $8 billion in foreign currency earnings to the country. It’s unlikely that the defendants in all these cases are barely making ends meet, saving up for the vacuum cleaner...

To make matters worse, the government now sees raising taxes on individuals as the easiest thing to do. In fact, in the long run, it will have complex and challenging consequences, ranging from the expected shadowing of the labor market and impoverishment of the already not-so-wealthy population to economic stagnation, triggered by a decline in consumer demand and a distortion of the already not very diverse economic structure.

Given our existing problems, we definitely do not need additional ones. Especially since money can be found in other pockets, by the way, closer to the Presidential Office.

*The survey was commissioned by ZN.UA and conducted by the Razumkov Centre’s sociological service from June 20 to 28, 2024. 2,027 respondents aged 18 and more were interviewed. The theoretical sampling error does not exceed 2.3%.

Read this article in Ukrainian and russian.

Please select it with the mouse and press Ctrl+Enter or Submit a bug

Login with Google

Login with Google