The Polish-Ukrainian catastrophe. What's next?

I believe that, as Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy prophetically said, there will be no border between Poland and Ukraine in the future...

Andrzej Duda (May 3, 2022)

We failed this exam. One of the most important and, at the same time, seemingly the easiest exams we faced after February 24, 2022. The easiest ones – because after the unprecedented solidarity that the Poles showed towards Ukrainians and Ukraine in the first months of the full-scale war, it seemed that now the solution to all our bilateral problems is self-evident. There were even illusions about creating the contours of the Baltic-Black Sea Union, which Ukrainian experts and even ex-presidents like to talk about from time to time. And, obviously, this is correct – you don't need to be a geopolitician, it is enough just to look at the map and remember history to notice that more or less long-term and stable statehood on our territory was only within the framework of a large union from the Baltic to the Black Sea. We are talking about Kievan Rus or the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Instead, as soon as misunderstandings and quarrels began, we immediately became part of large, foreign empires – whether from the East or from the West. However, beautiful and historically significant declarations are broken by the prose of everyday life, which requires compromises, willingness to listen to a different point of view, make concessions, maybe even lose money and ultimately change.

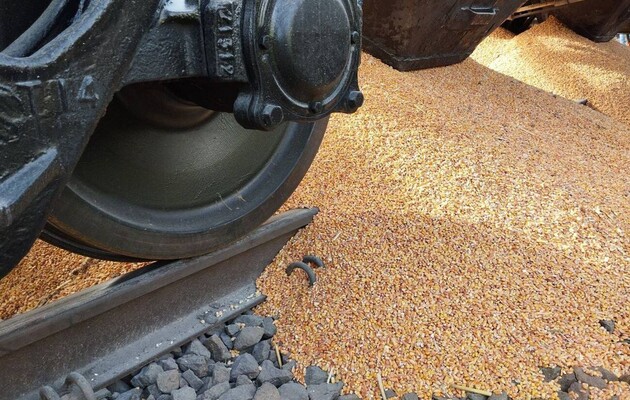

In the spring of 2022, Presidents Zelenskyy and Andrzej Duda talked about the fact that the Polish-Ukrainian border has become a formality, and later it will not exist at all. In February 2024, the border not only continues to exist, but it is also blocked, Ukrainian grain is demonstratively poured into the asphalt. In addition, a tractor driver passes by with a call to Putin to "restore order". It is difficult to call such a situation anything other than a catastrophe.

What led to this catastrophe and could it have been avoided? About the differences between the agricultural markets of Poland and Ukraine, large Ukrainian landowners and small Polish farmers, the transit of grain, which "in a strange way" began to enter the Polish market – all this has already been talked about quite a lot in the Ukrainian information space. However, this can be considered the cause of the economic dispute, but not the social and political tension that has been going on for more than six months. Agree that not every economic dispute turns into such a long-term crisis. After all, could individual groups of farmers or transporters block the Polish-Ukrainian border, for example, in March 2022? In those days, when Poles met Ukrainians in large numbers at the stations of their cities, accommodated our compatriots in their apartments and showed, perhaps, the greatest solidarity since the creation of the trade union of the same name in 1980. It is unlikely that the blockade of the border would be possible then. Why is the same society now either silent or taking the position "not everything is so clear" regarding the border blockade? So, the reason is deeper and more global than just the clash of economic interests. Ukraine has lost the trust and support of Polish society – and this is what has made possible the fact that the border blockade has become an element of the domestic political Polish game, and the Polish governments (both Mateusz Morawiecki and Donald Tusk) remain strikingly passive on this issue.

How did it happen? How in two years did we go from the unprecedented solidarity of Poles with Ukrainians to such a level of mistrust that enables the blockade of the border during the war? To try to understand this, it is worth following the trajectory of the development of Polish-Ukrainian relations over the past two years. A trajectory that, unfortunately, became a spiral of catastrophe.

First period. Positive

The full-scale Russian invasion for a certain time leveled all the long-standing disputes between Poland and Ukraine. In the face of an existential catastrophe, it is simply inappropriate to continue arguing about different visions of individual historical characters. Therefore, this topic then disappeared from the bilateral agenda. Instead, a large-scale volunteer movement appeared to support Ukrainians fleeing to Poland from the war. Recently, I had the opportunity to attend a student conference, thematically unrelated to Ukraine. And one of the lecturers asked the audience – young Poles from different regions of the country – who among them was involved in helping Ukrainians two years ago. Everyone raised their hands. And this is an excellent (and most importantly, quite typical) illustration of the scale of volunteer activity of Poles in the spring of 2022. Some call it "the second miracle of Polish solidarity" (the first was the 1980s and the events related to the trade union called "Solidarność").

On March 15, Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki and the leader of the Law and Justice (PiS) party, Jarosław Kaczyński, along with Slovenian Prime Minister Janez Janša and Czech Prime Minister Peter Fiala, became the first top-level European politicians to visit Kyiv after the start of the full-scale invasion. At the same time, Kaczyński became the first and only Western politician to propose the introduction of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) peacekeeping mission to Ukraine. In April, Andrzej Duda, along with the presidents of the Baltic states, became the first president to visit Kyiv after February 24, 2022. And Duda's visit to Kyiv on May 22, when he spoke in the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine with a proposal for a new good-neighborly agreement and financing of Ukraine's post-war reconstruction with frozen Russian money, was portrayed by the Polish press as historic, and many experts called it a long-awaited positive turn in Polish-Ukrainian relations.

That period was a wonderful window of opportunity to close once and for all all the historical disputes dividing Poles and Ukrainians. In part, the Poles were waiting for a certain gesture from the Ukrainian side on July 11, the day of remembrance of the victims of the Volyn tragedy. Such a gesture really was – it was on this day that Volodymyr Zelenskyy signed the law on expanding the rights of Polish citizens in Ukraine (this law mirrored the previously adopted Polish law on citizens of Ukraine). However, it was not a gesture that could finally close the topic of Volyn, but only a half hint of such a desire. The Ukrainian authorities decided to keep silent about the Volyn tragedy. And the adoption of this law became more of a diplomatic formality than real support, because it is worth asking the question, how many Poles really wanted to get a residence permit in Ukraine in 2022?

Fracture

The incident with the fall of a rocket in the village called Przewodów is often called the turning point when trust in Ukraine among Polish elites and society began to decrease (in particular, journalist Zbigniew Parafijanowych writes about this, citing sources close to the Polish government at the time, in the book "Poland at War"). More precisely, the turning point is not the incident itself, but the reaction of the Ukrainian authorities to it. The categorical denial of the very possibility that it was a Ukrainian air defense missile not only contradicted the official position of Poland, but also made it impossible to form a certain common Polish-Ukrainian position regarding this incident. After all, the then Minister of Defense of Poland, Mariusz Blaszczak, in view of this incident, put forward a proposal that the German "Patriot" air defense systems offered to Poland at that time should be handed over to Ukraine and placed along the Polish-Ukrainian border. If the Ukrainian side then supported this proposal, it would be possible to form a joint Eastern European (there is no doubt that the same Baltic countries would have joined such a Polish-Ukrainian initiative) diplomatic voice, which would be a powerful tool to pressure Western governments to accelerate the supply of weapons to Ukraine. But the political representatives of Kyiv went to a confrontation with Warsaw, from which no one won. The Polish Prosecutor's Office has suspended the investigation into the fall of a rocket in Przewodów in January 2024. The official statement said that the investigation was suspended due to... lack of cooperation with the Ukrainian side.

Inappropriate symbolism

The incident in Przewodów marked the beginning of a change in the trend in bilateral relations, but it was still a long way from today's catastrophic lack of trust. During 2023, there were several extremely inappropriate steps in terms of symbolism and media publicity, which significantly accelerated this trend. In May, the then spokesman of the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) Łukasz Jasina, in one of the interviews, asked a journalist, "Should Zelenskyy apologize for the events that happened in Volyn?" (I'll remind you that 2023 is the 80th anniversary of the beginning of the Volyn tragedy) answered that "President Zelenskyy should take on more responsibility."

And it is unlikely that anyone would have paid serious attention to this interview, had it not been for the disproportionately harsh reaction of the ambassador of Ukraine to Poland, Vasyl Zvarych. The next day, he not only accused Yasina of trying to impose on the president of Ukraine what he should do, but also emphasized the irrelevance of the formula "we forgive and ask for forgiveness" (which, in general, is not Polish-Ukrainian, but German-Polish and appeared in a completely different context) in the matter of Polish-Ukrainian historical reconciliation. There was a media scandal, most of the Polish mass media published the statement of the Ukrainian ambassador, and on the eve of the round anniversary, an atmosphere was created that was definitely not suitable for final reconciliation. Later, there was a good and promising speech in the legislative body of the speaker of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, Ruslan Stefanchuk, who spoke about the need to fill the aforementioned formula with real meaning, and then... nothing. Celebrations were held in Lutsk on July 11 with the participation of Duda and Zelenskyy, but no new reconciliation formula or anything that could put an end to the bilateral disputes over history was proposed. Moreover, in Duda's social networks post facto it was said that in Lutsk the memory of "killed Poles" was commemorated, and in Zelenskyy's social networks – "victims of Volyn".

Soon there was another media scandal, which almost repeated the May scandal of Yasina and Zvarych. This time it was about farmers' protests. In one of the interviews, the then acting head of the international policy office of the Office of the President of Poland, Martin Pshidach, said that "it would be worthwhile for Ukraine to start appreciating the role that Poland has been playing for it in recent months." Again, this very interview would hardly have gained public publicity if the Polish ambassador had not been summoned to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine (MFA) the next day to clarify these words. The same ambassador, Bartos Chihotsky, who was the only ambassador of a European Union country that did not leave Ukraine before February 24, 2022. Moreover, the summons of the Polish ambassador to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) took place on August 1, the day of commemoration of the Warsaw Uprising of 1944. On the day when mass patriotic actions traditionally take place in Warsaw. Is it worth saying how it affected public opinion about Ukraine in Poland? And how many speculations there were in social networks about the fact that Ukraine "congratulated" the people of Warsaw with their anniversary...

Later, mutual public attempts to "bite" each other became regular. From the Polish side, this can be explained by the campaign on the eve of the elections to the Sejm of the Republic of Poland. The Law and Justice Party (PiS) tried to mobilize the conservative-nationalist electorate, and it was important for them to show that the interests of Poland were more important to them than the "Ukrainian issue". In general, during the pre-election period, Polish political elites showed themselves as Europeans – in the worst sense of the word. When British, French or German politicians use the topic of the war in Ukraine in their own internal political struggle, it is cynical, but understandable. War is far from them, and for their societies it is rather an abstract concept from TV. But when representatives of the Polish political community failed to raise the issue of war and support for Ukraine over political divisions, it raises questions. At the rhetorical level, everyone (except perhaps the far-right "Confederation") recognizes the existential importance of Ukraine's victory for the future of Poland. But when it comes to specific matters, it turns out that support for Ukraine in this war can be put "in a long queue" before the fight for this or that part of the electorate. Such behavior became noticeable during the election campaign and even more obvious during the border blockade, but more on that later.

From the Ukrainian side... it is difficult to explain some actions of domestic officials. Let's say, why did Ukraine's trade representative Taras Kachka post on Twitter on September 18 (the day Ukraine filed a lawsuit against Poland at the World Trade Organization (WTO)) in Polish: "I care about your and our agriculture"? Such a reference to the phrase "For our and your freedom" (which appeared during the November Uprising of 1831) was perceived simply as contempt for Polish history and an attempt to mock the Poles. And the very next day, President Zelenskyy from the United Nations (UN) podium almost accused Poland of working for the Russian Federation. Andrzej Duda responds with an equally inappropriate comparison of Ukraine with a drowning man (we remember the height of the election campaign in Poland). Even then it was possible to say that not a trace remained of the solidarity that existed in the first months of the full-scale war.

Subsequently, another scandal was caused by the Polish Institute of National Remembrance (INR), which in December froze the investigation into the "Vistula" action with the absurd explanation that it was a "preventive" measure that did not have a repressive nature. It is quite likely that this "extravagant" (actually scandalous and neither historically nor politically justified) decision was an attempt by the current conservative leadership of the Institute of National Remembrance (INR) to loudly "slam the door" (and at the same time play along with the voters of the Law and Justice party (PiS)) against the background of rumors about the intention of the new government to prematurely change the leadership or even liquidate the Institute of National Remembrance (INR). And once again the Polish-Ukrainian dialogue became a victim of internal political processes in Poland. If earlier it was possible to claim that due to all the problems with the Volyn tragedy, the question of the "Vistula" action in bilateral relations was finally closed (after all, the Polish Senate condemned it as a crime of the communist regime of the Polish People's Republic back in 1990), then with this decision the Polish Institute of National Remembrance (INR) created the problem again – literally on the same spot.

Border

Parallel to all the scandals mentioned above, the grain crisis and the protest of transporters also developed. The border blockade began in the fall, when the atmosphere in bilateral relations and mutual trust (both at the political and social level) had already been undermined. In addition, the process of transit of power was taking place in Poland, on which many Ukrainian publicists and observers placed special hopes. "Pro-European" Donald Tusk, in their opinion, should have taken a tough stance on carriers and quickly unblocked the border. This did not happen. The border blockade became an element of internal political struggle in Poland. The representatives of the Law and Justice Party (PiS) are trying to use the situation at the border to further destabilize the situation in the country and lead to elections, while the coalition government (with the Polish Peasant Party as part of it) is trying to win favor with the relevant electorate, which supports the demands of the protesters. Disillusioned with Ukraine, Polish society remains quite passive, especially since the farmers and transporters are partially right, so even those who condemn their methods recognize the very right to protest.

Is Ukraine defending Poland?

The last and seemingly concrete argument used by Ukrainian publicists and politicians in this topic is that Ukraine protects Poland from the Russian invasion at the cost of a heroic struggle. And in this situation, blocking the border is simply immoral, regardless of any economic interests. However, unfortunately, this argument has less and less effect on the Polish government and society. First, there is an awareness that the security of Poland today depends to a much greater extent on the unity and defense capability of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the Western world in general than on the success of Ukraine's defense. Secondly, a society of almost 40 million people cannot maintain the same enthusiasm and fervor in support of Ukraine for two years as in the first few months of a full-scale war. A long war requires strategic and systemic thinking, particularly in diplomatic relations with neighbors. It is worth noting that Ukrainian diplomacy is reactionary. Ukrainian officials react to certain events after the fact, when they have already happened. In addition, they often react too emotionally and inappropriately, trying not to reach a compromise, but to bend their own line without considering the possible consequences. At the same time, in the situation with Poland over the past two years, the specifics of Polish political culture, the expectations of Polish society, and sensitive topics for this country have not been taken into account. One gets the impression that in the Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) and the office of the President of Ukraine, the Polish direction is handled by people who either frankly do not like this country, or have never been to Poland and have never spoken to a living Pole. It was the lack of feeling for Poland, combined with the lack of Ukraine's strategy for Poland, that led to the fact that Polish society ceased to be sensitive to the Ukrainian war.

In addition, the tactics of not recognizing the protesters' right to negotiate with the Ukrainian side proved to be ineffective. If Ukrainian diplomats have appeared at the border in recent months, it was only to communicate with the police or Ukrainian drivers stuck in queues. At the same time, there were attempts to talk with government officials in Warsaw. There were no negotiations with the protesters themselves, only hints (or even direct accusations) that their actions support the Russian Federation, and the expectation that the Polish government or European Union officials will resolve the situation. Instead, the protestors' claims (both transporters and farmers) were directly related to Ukraine. Moreover, farmers' protests are not a narrow bilateral topic, but a pan-European trend. Therefore, whether our diplomats want it or not, we will have to deal with farmers and seek compromises with them. Otherwise, such protests will accompany Ukraine's already difficult path to membership in the European Union.

However, the reluctance to communicate with the protesters shows another symptom characteristic of the Ukrainian (post-Soviet) style of diplomacy – it does not recognize society as a side of the dialogue. Therefore, Ukrainian diplomats actually do not work with the societies of other countries. This is where the numerous problems with unsuccessful statements, the inability to find an acceptable formula for reconciliation on historical issues, inappropriate symbolism, and ultimately with the protesters at the border come from. Not everything can be solved through power, especially in democratic countries, where any politician makes every move based only on ratings.

Russian trace

Is there a Russian trace in all this history? Obviously and definitely. You have to be a very naive person to believe that the Russians will not use such a convenient excuse to create discord between Poles and Ukrainians. A sign of Russian intervention may be the ardent support for the blockade by openly anti-Ukrainian political groups, but above all, the presence of a Russian trace in this history is evidenced by the scandalous events of recent weeks. Actions with the scattering of grain on the roads do not make any practical sense for the protesters themselves, on the contrary, they cause incredible damage to the perception of Poland in Ukraine. This is an open provocation, the purpose of which is far from protecting the rights of Polish farmers. And it is quite possible to assume that the idea of this provocation was not created in Poland. The second, even stronger provocation, was the tractor driver's appeal to Putin to "bring order" with Ukraine, Brussels and the Polish government. It is good that this subject has already been taken under the control of the Polish prosecutor's office. The longer the blockade lasts, the more such provocations may occur.

However, understanding this, one should avoid the temptation to accuse all protesters of working for the Russian Federation. One of the leaders of the protest, Michal Kolodziejczak, was first elected to the Sejm of the Republic of Poland from the "Civil Coalition", and in December (while the blockade was still going on) – became the Deputy Minister of Agriculture of Poland. Therefore, if we generalize, we can quickly come to the conclusion that Donald Tusk is also an agent of the Russian Federation. And this is definitely a road to nowhere. Russian influence exists, but it does not exclude the very problem that needs to be solved. If there is no problem, there will be no opportunity for the Russian Federation to arrange further provocations.

What happens next?

First of all, it is necessary to put out the flames and stop the blockade. President Zelensky's proposal to hold a meeting at the highest level directly at the border could be a good step in this direction. As well as Prime Minister Tusk's proposal to recognize border checkpoints as critical infrastructure, which will make it impossible at the legislative level to hold protests and blockades there.

However, Tusk rejected Zelensky's proposal, and here it is worth paying attention to the argumentation. "The Ukrainian side also understands that it is better to conduct these negotiations at the technical level, so that the government meeting does not have a symbolic value – because we do not need symbolism in relations. The whole world sees how determined we are to help Ukraine, and there is no need for further bright gestures of solidarity." Well, even after Tusk's January visit, which was cool (in terms of weather and atmosphere), it was possible to note, and after these words, it can be confidently asserted that the romantic period in Polish-Ukrainian relations has ended even at the level of political rhetoric. If the Ukrainian side understands this and begins to interpret relations with Poland from the position of pragmatism and negotiation ability, it can turn into a plus.

But what was definitely surprising in Tusk's words was the proposed date of the government meeting in Warsaw – March 28. That is, the Polish Prime Minister proposes that the problem of the border blockade remain unresolved for more than a month. And this is during a full-scale war in our country.

In response to this statement, Ukrainian government officials decided... to come to the border, take a photo and declare that the meeting did not take place because the Poles did not come. For whom and why was this demarche made, and most importantly, what exactly will such a diplomatic performance of the authorities do to solve the problem? These questions are obviously rhetorical.

Ukrainian diplomacy needs to grow up. Stop trying to create a show, stop playing cynicism, stop trying to "break the arms" of partners (especially partners on whom the supply of weapons largely depends). It is necessary to learn to think strategically, to be ready for dialogue and compromises, to work not only with elites, but also with societies.

But the main thing is that Ukraine must answer the question: what do we want from Poland? How does Ukraine see Polish-Ukrainian relations in five, ten, twenty years? What strategic vision of the future does Ukraine offer to Poland? And in the future, be guided by this information.

Predictability is one of the main features required for establishing a successful bilateral partnership. Without a clear strategy, another crisis, supplemented by short-sighted statements by politicians on both sides, is only a matter of time.

Read this article in Ukrainian and russian.

Please select it with the mouse and press Ctrl+Enter or Submit a bug

Login with Google

Login with Google