"Ballad of the Frailty of "Druzhba"

The transit of oil from the east may end in a few years.

The system of transit oil pipelines from Russia to Europe is called "Druzhba". The name now sounds ironic, and there are fewer and fewer friendly destinations.

At the beginning of the 2000s, friendship with the Baltic states disappeared, then the Kremlin shut down the section going there for "scheduled repairs", which dragged on forever.

This year, it seems, there will be no more transit of the northern branch of the "Druzhba" oil pipeline to Poland and Germany. In 2022, another 24 million tons were pumped there, in the same year, both Berlin and Warsaw refused to buy oil from the aggressor.

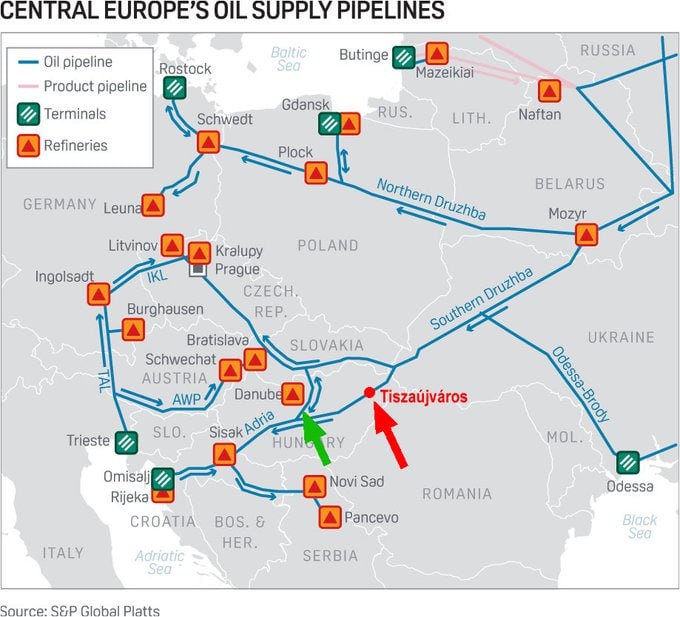

Ironically, only one "Ukrainian" part of the oil pipeline, through which oil goes to Hungary, Slovakia and the Czech Republic, remained for the workers, although its prospects are not indifferent. Actually, the very fact that this section of transit is still working is due to a complex balance of interests and contradictions.

The European Union has introduced an embargo on Russian oil and oil products, but it does not apply to deliveries via the southern branch of the "Druzhba" oil pipeline.

However, with the beginning of the great war, an open joint-stock company called "UkrTransNafta", which is the operator of our section, sharply raised prices. If at the beginning of last year, transit cost 8.6 euros per ton, then the price was raised several times both last year and this year. Since June, it has been twice as high as before the war – 17 euros/ton, and will rise to 21 euros from August. They wanted 27.2 euros/ton in general, but so far they have not agreed. And it's worth it, because in other directions the tariffs are even higher.

The deliveries themselves in 2022 have even increased slightly. Thus, 4.9 million tons were pumped to the Hungarians (45% more than the pre-war year), 4.2 million tons to the Czechs (an increase of 25%). Only the Slovaks bought, as before, 5.2 million tons.

Purchases took place against the background of shelling of the infrastructure (the pipe itself, however, was not hit) and fears that transit would be interrupted. However, serious failures were avoided.

Moscow tried to transfer the payments to ruble accounts, which caused the transit to stop for several days. Ukraine rejected these demands. In fact, oil is pumped for Hungarian MOL (it owns refineries in Hungary and Slovakia) and Polish PKN Orlen, which owns a plant in the Czech Republic. Against the background of the failures of the "successful military operations of the second army of the world", the Kremlin did not risk quarreling with Orban, and the issue of the currency of payment was settled by the oil buyers.

At the beginning of the year, according to leaked United States of America intelligence documents, the President of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, proposed to study what would happen if the "Druzhba" oil pipeline was stopped. Political figures in Budapest even began to worry about this. However, there was a game on nerves. Although politicians in Kyiv are not happy with Orbán's position, it will not interrupt the transit.

As a result, Ukraine receives diesel fuel – 114,000 tons in 2022. Which is not superfluous both for agrarians and for the Armed Forces of Ukraine. At the same time, money from transit makes it possible to support the operation of oil pipelines that pump Ukrainian oil.

Neighbors in Central Europe – three landlocked countries receive a resource for processing and ... time to diversify supplies.

That's why they started diversifying. Before the war, Slovakia was completely (95%) dependent on Russian oil, Hungary – 60-65%, and the Czech Republic – half.

Already last year, the countries increased supplies via an alternative route – the "Adria" oil pipeline from the Croatian port of Omisal on the Adriatic Sea, which was laid under the Yugoslav communists (see Fig. 2). Ironically, once through it, an open joint-stock company "UkrTransNafta" was going to develop transit supplies of Tyumen oil.

In addition, the Czechs, together with the Austrians and Germans, will work on the modernization of another pipe – the Transalpine Pipeline (TAL) from the Italian port of Trieste. Polish PKN Orlen, which stopped buying oil through the northern branch of the "Druzhba" oil pipeline in the spring, promises to exclude Russian oil from its refineries in the Czech Republic. The agreement to increase the throughput of TAL to 4 million tons per year will allow the Czech Republic to get rid of its dependence on Russia as early as 2025.

For the Hungarians, the situation is a bit more complicated, they are going to expand the volume of Croatian transit there, but they do not want to give up the "Druzhba" oil pipeline completely yet. MOL is working on diversifying oil supply routes and expects to be able to choose between Urals and non-Russian oil for its refineries by 2026.

Their relations with Croatia are cheerful. So, back in 2009, MOL bought 49% of the local oil and gas concern INA (another 45% from the Croatian government). The result of the agreement was a criminal case against Croatian Prime Minister Ivo Sanader. He was accused of accepting bribes from Hungarians. And in November 2012, the former prime minister was sentenced to ten years in prison. Naturally, MOL does not recognize the bribe, but such nuances (as well as Zagreb's appeal to international courts to terminate the contract) did not really strengthen "good cooperation".

Now the excitement has subsided a little, but when the long-term transit oil contract with Zagreb expired this year, they could not conclude a long-term replacement agreement (despite a year of negotiations). Hungarians accuse their neighbors of an inflated price tag for pumping – four times more expensive than they would like. Currently, a temporary contract for one year has been concluded. In general, "sworn friends".

Technically, to increase the capacity of "Adria" it will be necessary to strengthen the pumping station and modernize the approximately one hundred kilometer section of the oil pipeline, which requires investments in the amount of 100-200 million euros. By the way, during the forty-odd years of its history, "Adria" has never worked even at half capacity.

At the same time, Budapest is trying to enter the Serbian market, offering to lay a pipeline there from "Druzhba" (however, it offers to look for money in the European Union).

But, despite the nuances, the replacement of the Russian export mixture Urals is actively proceeding.

By the end of 2023, Slovakia wants to reach about a third of the processing of non-Russian (mainly Azerbaijani) oil. This is a minus of almost 2 million tons of transit through Ukraine.

Hungary, where before the war the share of Russian oil was about 60%, wants to reduce it to 40%.

Moreover, the European Union stimulated this process by banning the export of petroleum products produced from Russian raw materials. Slovak refineries exported up to half of their total volumes to the Czech Republic. And until the end of 2024, diesel fuel produced from Russian oil will still be able to be sold from Slovakia to the Czech Republic (and only there).

In Hungary, such a postponement is valid until December 2023. Even if it is extended for another year (and there are such attempts), both directions (Hungarian and Slovak) will settle down nicely.

Both Czech-Polish and Hungarian transit routes promise to be put into operation in the second half of 2025 with a corresponding reduction in transit through Ukraine. Instead of the current 10 million tons pumped to Hungary and Slovakia, an open joint-stock company "UkrTransNafta" will have 3.5–4 million tons left in two to three years. The Czech Republic with its 5 million tons will go to zero in general.

Internal transit of its oil (1.5–2 million tons) will not make up for such losses.

After unlocking the ports, transit from the sea will appear. But so far it is not much.

In June, they again mentioned the construction of the "eternal" oil pipeline Brody-Adamova Zastava. At the negotiations with the Polish PERN, it was mentioned that it will connect the Ukrainian and Polish oil transport systems, highly evaluating the degree of readiness for implementation. These words are imprecise, without the slightest specificity, the project has not been developing for twenty years. Although it was emphasized that (when it comes to the metal) the pipeline will pump in both directions. And this will give Ukraine the opportunity to receive oil from the Baltic Sea. It is promising for Poland as well as for other countries of the European Union, but... only after unlocking Ukrainian Black Sea ports.

The traditional question "Who will pay for the construction?" – no answer, and where to get the resource? Although the project in the European Union is included in the priority list, there is no clarity at the moment. All the more so since it really promotes the diversification of energy supply routes to the European Union market, which immediately cuts off political feet.

One thing is clear for sure – there will be no the "Druzhba" oil pipeline. What will happen after the "Druzhba" oil pipeline? So far, transformations are on the march, and it is difficult to say when and with what they will end. But the fact that the market will change beyond recognition, probably, as well as the fact that it is time for Ukraine to find a place on it now, while there are still free seats. It won't happen soon... At the very least, it is necessary to develop, or rather, to revive the same oil processing. It will not be easy and quick. Losses are also inevitable. But burying your head in the sand, expecting that somehow everything will resolve itself, will not work.

Read this article in russian and Ukrainian.

Please select it with the mouse and press Ctrl+Enter or Submit a bug

Login with Google

Login with Google