We all have an idea of what the “Russian world” brings with it. That is why we resist it with such ferocity, much to the astonishment of our allies.

Yet it is one thing to have an idea and quite another to know for certain.

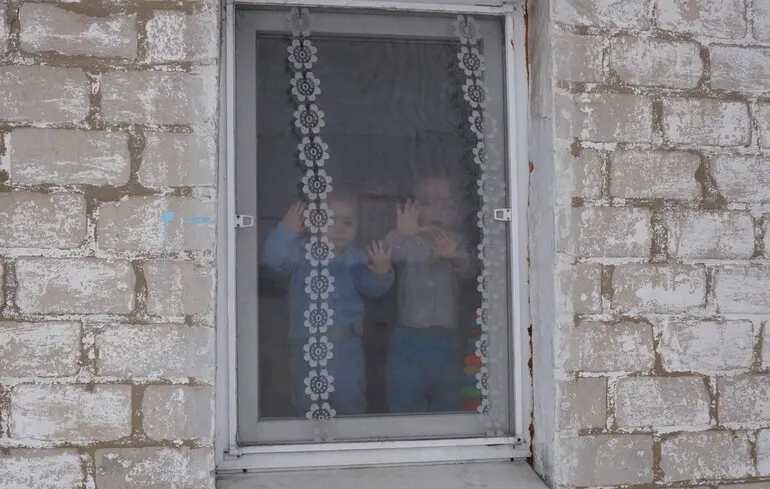

The Donetsk and Luhansk regions have been under occupation since 2014. This autumn, children living there entered the fourth grade. They are Ukrainians only by birth—and they don’t even know it. They consider the “Donetsk and Lugansk People’s Republics” to be their homeland, while we once coined the clumsy acronym CADLR—“Certain Areas of Donetsk and Luhansk Regions.”

More than ten years have passed—enough time to measure the changes and see how the “Russian world” transforms any land once its footsoldiers touch the ground.

Analysts of Ukraine’s Defence Intelligence constantly monitor the situation in the occupied Donetsk and Luhansk regions. In preparing this publication, they agreed to share with ZN.UA a number of statistical findings and assessments.

In addition, we asked refugees from those territories to contact their relatives and friends still living there and tell us about everyday life under occupation. For safety reasons, their names are not disclosed.

The point of departure

In 2012, Donbas stood at the peak of its prosperity.

During preparations for the European Football Championship, colossal sums were poured into infrastructure. Donetsk gained a brand-new airport terminal, and the city as a whole took on a modern, flourishing look.

A native of the region, Viktor Yanukovych, was then-president of Ukraine. Following in his footsteps, other Donbas natives headed all the key ministries and held the largest faction in parliament. As people joked at the time, in Donetsk they were catching passersby on the street to send them off to run something in the capital. Only one region, Lviv, had an administration not led by someone from Donetsk or Luhansk.

Donbas shaped the country’s political destiny. Home to roughly one-fifth of Ukraine’s voters, it could easily tilt the national electoral balance in the desired direction.

Its influence was not only political but also economic. The region hosted the headquarters of several major corporations that united entire production chains—from the extraction and processing of raw materials to the production of steel, energy and machinery. Unsurprisingly, the largest of these enterprises belonged to Rinat Akhmetov, Ukraine’s wealthiest man. Yet the second-tier oligarchs were not worse off either.

The region’s substantial contribution to the national economy gave rise to a local slogan: “Donbas feeds all of Ukraine.” Subsequent events, however, showed how exaggerated that claim was—the country did not starve without the region.

Office employees, miners and factory workers enjoyed stable and relatively high wages—on average, about a third higher than the national figure. Small and medium-sized businesses thrived, catering to workers eager to spend their paychecks on goods and services brought in from all over the world.

The overwhelming majority of residents spoke Russian from birth and attended churches of the Moscow Patriarchate. Rare and unsystematic attempts to change these preferences met a sharp and often aggressive reaction.

The pact with the devil

A few weeks after the annexation of Crimea, Russian security services began stirring unrest across Ukraine’s eastern and southern regions. After failing in Kharkiv, Dnipro, Zaporizhzhia and Odesa, Moscow concentrated its resources and attention entirely on Donetsk and Luhansk.

The streets were flooded with imported provocateurs; television broadcasts—with aggressive propaganda. The situation was being shaken deliberately and persistently.

Eventually, the effort paid off. On the night of April 11–12, 2014, a detachment led by Igor Strelkov crossed the Russian–Ukrainian border and seized Sloviansk. A few local residents joined them. A group of Ukraine’s Security Service (SSU) officers who came to negotiate was ambushed and shot dead.

The hostilities began. At the same time, preparations were under way to legitimize the occupation. In May 2014, under the occupiers’ control, a “referendum” was held in which residents of Donbas allegedly supported the creation of two “people’s republics” in Donetsk and Luhansk. There was no way to verify the announced results: voter lists, protocols and ballots had no electronic copies, were never consolidated into a central database and were promptly destroyed.

Even so, some share of the population in Donetsk and Luhansk did support separation from Ukraine and annexation by Russia. According to a poll conducted in March–April 2014 by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (commissioned by ZN.UA), 27.5 percent of Donetsk residents and 30.3 percent of Luhansk residents said they wanted their oblast to become part of the Russian Federation.

Why? What had they been promised—and what were they expecting?

First, peace. Having provoked war, the Russians assured locals they could protect them. No one, they said, would dare touch people under the protection of a “mighty country” and “the world’s second army.” In reality, open separatism only fanned the flames of conflict.

Second, the defence of language rights. Eager to appear more democratic than the so-called “Nazi regime in Kyiv,” the self-proclaimed “DPR” enshrined two “state languages”—Russian and Ukrainian—in its pseudo-constitution. Every trace of the latter has now been erased from the region’s media, education, culture and urban space.

[pics_lr left="https://zn.ua/img/forall/u/667/61/69bb4c1a-538bfad286e661696e10791982e288d0(2).jpg" ltitle="" right="https://zn.ua/img/forall/u/667/61/GettyImages-464120406(2).jpg" rtitle=""]

Third, accession to the Russian Federation. Instead, Moscow entered peace talks insisting that Donbas was Ukrainian territory, while maintaining de facto control to keep the region in a legal “grey zone.” Unsurprisingly, this limbo devastated the economy and, with it, local living standards.

And finally, higher wages and pensions. The promise of higher pensions especially thrilled those who sympathized with Russia. Salaries appealed more to police and other security forces, while private-sector professionals and entrepreneurs were skeptical from the start. The latter were used to earning through skill and quickly saw the grim prospects. Pensions, however, were the most coveted expectation, even a dream.

Interestingly, the promises were formally fulfilled. Yet that is the essence of a pact with the devil: he never lies outright—he simply leaves things unsaid.

Higher wages? Certainly—but only for the forcibly mobilized “cannon-fodder assault troopers.”

Higher pensions? Of course—though until February 2022, they required humiliating “pension tourism.” To receive both their Ukrainian pension and occupation benefits, people resorted to elaborate schemes. Despite their professed hostility to Ukraine, local pensioners made up the majority of passengers on the humanitarian buses crossing the front line—and the long queues at Pension Fund and Oschadbank offices in nearby government-controlled towns.

With all of this came expensive food, ruined infrastructure and life in a war zone under constant shelling.

Inclusion into the Russian Federation? “Soon,” they were told. Just a little patience—eight years, as it turned out.

As for the Russian language—yes, Ukrainian has been eradicated. But a new irony has emerged: in some neighborhoods, Donetsk and Luhansk residents now have neighbors who barely speak Russian at all, preferring the languages of the Caucasus and Central Asia.

In 2014, Russia painted bright, tempting prospects to win over the people of Donbas.

Now, we can see what those promises have turned into.

Drought

At the start of the full-scale invasion, a Jewish family managed, through extraordinary effort, to evacuate their grandmother from Donetsk. Instead of gratitude, however, she scolded her relatives and kept demanding to be taken back home. A reaction not uncommon among the elderly of Donetsk—many responded this way to forced evacuation.

One day, she called her relatives in Donetsk again, repeating her demand.

“Grandma Sofa,” came the polite reply, “you know there are many of us here in the apartment. But you don’t know what we do in the morning.”

“What?”

“We pour half a glass of water—no more!—and brush our teeth. Do you know what we do after that?”

“What?”

“We poop.”

“Well, that’s good!”

“Maybe. But do you know what we do at noon? We poop again.”

“Alik, what are you talking about?”

“You’ll understand in a moment. And that’s how we spend the whole day—pooping…”

“Alik, stop it!”

“…and in the evening we flush it all away with a single bucket of water. Just one, no more!”

The water crisis now defines daily life in Donetsk.

The problem had been long foreseen. Between 2014 and 2022, the water supply system survived only thanks to a fragile set of arrangements reached during the Minsk negotiations.

The sources that provided water to residents of occupied Donetsk and Luhansk were—and still remain—under Ukrainian control.

In Donetsk oblast, water was pumped from the Siverskyi Donets River in the north and, through a sprawling network of canals, pipelines, filtration and pumping stations, delivered across the region, as far as Mariupol on the Azov Sea coast.

Both sides were hostages to each other on this issue: it was impossible to deliver water from, say, Sloviansk to Pokrovsk without passing through CADLR, that is, via Horlivka, Makiivka and Donetsk. Even in periods of intense fighting, both sides readily agreed to temporary ceasefires to allow repair crews onto the pipelines.

The vast infrastructure was managed by Voda Donbasu (Water of Donbas), formally a communal enterprise of the Donetsk Regional Council. Under the same name, some of its divisions had to remain in CADLR to oversee the system’s operation. Because of this, its managers regularly faced interrogations by Ukraine’s SSU, fines and even criminal proceedings.

In Luhansk oblast, the International Committee of the Red Cross stepped in as an intermediary, setting up a mechanism to process payments for drinking water supplied from government-controlled territory to occupied Luhansk.

It is hard to say what the Russians expected when they launched the invasion in 2022.

Perhaps to seize Sloviansk quickly and take control of the starting point of Donetsk’s massive water network. But since 2014, Ukraine’s army had been steadily fortifying this area. Sloviansk remains unconquered—and there seems little reason to fear that will change anytime soon.

Perhaps they counted on new pipelines from the Don River. But although a new branch was built, it failed to meet the region’s needs and made little difference overall.

For a time, the region survived thanks to four large reservoirs of the regional water supply system. Eventually, they too ran dry—and Donetsk was struck by a real drought.

Today, in the occupied regional capital, water is supplied twice a week for three hours at a time. The entire rhythm of urban life revolves around this schedule. During those rare hours, people must bathe, wash clothes and fill every available container. On those days and hours, no one arranges business meetings, lingers at work, hosts friends or walks their pets. The streets empty out—everyone rushes home with one thought: to make it in time at any cost.

Those described are the lucky ones, people who still have access to water.

For many others, it’s worse. In numerous high-rise apartment blocks, the aging and half-empty pipelines can no longer push water higher than the third or fourth floor. Residents must race downstairs with buckets and plastic jugs to catch what little water flows from the basement pipes. This, unsurprisingly, breeds resentment among “luckier” neighbors and often sparks conflicts.

The drought has created its own economy. Across Donetsk, apartment buildings are now wrapped in tangled webs of plastic hoses, installed by enterprising plumbers. Some secretly tap into basement pipes to make private illegal connections; others set up additional tanks and pumps on higher floors to push water upward and store a few days’ supply.

From time to time, the occupation authorities send water trucks through the neighborhoods, instantly drawing long queues.

[pics_lr left="https://zn.ua/img/forall/u/667/61/GettyImages-1238725378.jpg" ltitle="" right="https://zn.ua/img/forall/u/667/61/GettyImages-1241143983.jpg" rtitle=""]

At other times, Russian soldiers, facing the same shortages, drive around the same courtyards and drain those tanks for themselves.

Beyond scarcity, the quality of the water itself is a major issue. Any household filter installed in an apartment clogs within a week.

Denis Pushilin, head of the occupation administration, reacted to the water collapse energetically. First, he quickly blamed Ukraine for everything. Second, according to his former ally and now dissident ideologue of the “Donetsk Republic,” Andrei Purgin, Pushilin organized the sale of purified water through his own network of stores and vending machines.

The last drop (pardon the black humor) is that the water that is absent from the taps most of the time and filthy when it does appear keeps getting more expensive. Between 2014 and 2022, the occupation authorities in Donetsk deliberately kept utility prices low to make life under the “DPR” appear better than in government-controlled territory. The Ukrainian government, in turn, faced constant criticism for continuing to supply water and other resources across the line, despite the enormous costs of this humanitarian policy.

But with the formal annexation of CADLR and its inclusion in Russia’s constitution, even that illusionary advantage vanished. Utility rates are now raised twice a year. Officially, they are not “increased,” of course, but “aligned with the Russian average.”

At the time of occupation, one cubic meter of drinking water cost 3 hryvnias (roughly $0.3).

In 2015, the first “DPR” leader, Aleksandr Zakharchenko, issued a decree keeping the rate almost unchanged, at 3.3 hryvnias (yes, he set the tariff in hryvnias!).

Now, after all the “alignments,” a cubic meter costs 41 rubles, according to Ukraine’ Defence Intelligence data—roughly 20.5 hryvnias at the 2022 exchange rate.

In occupied Luhansk, the story has been less catastrophic. As early as 2014, the local occupation administration adopted a program to gradually replace Ukrainian water supplies by drilling wells. As a result, Luhansk has no acute shortage of water—but the price was paid by the residents themselves, through skyrocketing utility bills.

The first consequences of this massive shortage are already alarming. Farmers lost their crops during a dry, hot summer as both natural springs and irrigation systems dried up. The power plant in Zuhres—which supplies electricity to occupied Donetsk—has repeatedly shut down in emergency mode due to lack of water. Even the toxic-waste ponds near Toretsk are drying up, concentrating phenol residues into ever more poisonous mixtures.

A natural question arises: why were wells drilled in Luhansk but not in Donetsk?

Because there is no groundwater beneath Donetsk. Beneath its soil lie closed and flooded coal mines filled with mineral-saturated liquid that can only metaphorically be called “water.”

And speaking of mines…

Requiem for industrial Donbas

Donetsk and Luhansk regions are dotted with relics of socialist realism—that Soviet art form that glorified the miner’s labor. Bas-reliefs, mosaic panels, monuments. The offices of local officials and the halls of culture were filled with paintings and tapestries, souvenir figurines, and commemorative photo albums.

[pics_lr left="https://zn.ua/img/forall/u/667/61/GettyImages-1986360222.jpg" ltitle="" right="https://zn.ua/img/forall/u/667/61/photo_2025-10-23_23-10-41.jpg" rtitle=""]

Today, however, they are no longer monuments.

They are memorials.

More than a century ago, the region’s rich coal deposits became the starting point of its rapid development and prosperity. They first attracted foreign entrepreneurs who, with the permission of the Russian Empire, built mines, workers’ settlements and entire towns, leaving behind place names of strikingly foreign origin: Bosse, Ostheim, New York.

Later, these enterprising Europeans were replaced by Stalin’s architects of industrialization.

The coal industry became the backbone of the region’s prosperity—and of its folklore, urban identity and collective pride. In the first years of Ukrainian independence, “black gold” turned a new generation of nouveau riche into fantastically wealthy men.

All of Donbas revolved around miners and mines, much as our galaxy orbits the massive black hole at its center.

That was the case until the “Russian world” arrived.

In 2014, on the eve of war, Donetsk and Luhansk regions together had 114 operating coal mines.

Today, according to data from Ukraine’s Defence Intelligence, only 15 are working.

Experts at Ukraine’s National Academy of Sciences, who specialize in this field, give an even lower figure in a conversation with ZN.UA: seven.

The discrepancy arises because intelligence analysts count all functioning enterprises, while scientists include only those that still extract coal. Half of the remaining mines operate merely as underground pumping stations, preventing neighboring shafts from flooding.

Whatever the metric, the conclusion is clear: coal mining as an industry has ceased to exist.

It was not unexpected. Even in 2014, experts warned that this would happen. Russia already had a surplus of coal on its own market and was closing down domestic mines. It was never likely to invest in maintaining or developing captured enterprises on foreign soil.

The outcome was easy to foresee. One had only to look at Donetsk in Russia’s Rostov region—the namesake of the Ukrainian city—which had sunk into poverty after mass mine closures.

Russian occupation has placed a full stop at the end of Donbas’s industrial history.

With the coal industry gone, so too have the other sectors built upon it—those that once transformed local raw materials into steel, chemicals and energy.

Between 2022 and 2024, the region lost its major industrial giants: the metallurgical plants of Mariupol, the coke plant in Avdiivka, the Azot chemical plant in Sievierodonetsk and others.

The few enterprises not destroyed by the fighting now barely flicker to life. Alternative jobs are scarce; the regional economy had been built too tightly around its heavy industry.

“The Russian World” took away people’s jobs

In 2012, unemployment in Donetsk and Luhansk was minimal: 8.5 percent in Donetsk oblast and 6.9 percent in Luhansk. Moreover, many of those officially counted as unemployed were in fact working in the shadow economy. Along the border, smuggling was common; criminal networks ran underground factories producing counterfeit cigarettes and alcohol; in many districts, small illegal pits—kopanky—quietly extracted coal beyond any official record.

In 2025, analysts from Ukraine’s Defence Intelligence describe an apocalyptic picture. Because of the war, more than 3,000 small and medium-sized enterprises have completely ceased operations, leaving former miners from shuttered coal pits with no alternatives.

As a result, no more than 30 percent of local residents have any job at all. The unemployment rate in CADLR has tripled compared to 1992, when the region’s economy was painfully transforming from Soviet central planning to market mechanisms.

Since 2014 and still today, in most families across the occupied areas, only one person has any source of income. So when discussing wages or pensions, one must remember: each sum must be divided among three or four dependents. This sharply contrasts with families in government-controlled Ukraine, where nearly everyone except minors earns some money.

This, perhaps, is the main difference in how the standard of living is measured in the occupied regions. Before the war, the vibrant local economy could provide work for anyone willing to work. Living off one’s relatives was shameful. “So you don’t work anywhere? Why?” people would ask with disapproval.

Now, being unemployed carries no stigma. There are too many of them—and too few options.

One can become a collaborator and take a job in the occupation administration.

Apart from the military, Russia pays the most to police and other security personnel, as well as to teachers and doctors. Oddly, though, salaries for social workers, utility employees and civilian administrators are meager.

Wages across these groups vary unevenly. In territories occupied since 2022, workers receive a “federal supplement” for serving in a combat zone. In the areas Russia seized back in 2014, such privileges don’t exist.

Once, a group of teachers from Donetsk went to rural districts to run professional training courses for their colleagues. In conversation, they discovered that rural teachers were earning a third more than their counterparts from the “capital.” With the federal bonus, they received 40–45,000 rubles (about 20–22,000 hryvnias, or $480–525).

Not a bad income, in fact. And indeed, Russia is investing heavily in teachers—for an obvious reason.

The International Criminal Court has issued arrest warrants for President Vladimir Putin and his children’s rights commissioner, Maria Lvova-Belova, over the physical abduction of Ukrainian children.

But another form of abduction goes less noticed: the mental one. Russia is pouring vast resources into raising Ukrainian children in occupied territories as Russians. Education there now merges with military training and a program of aggressive “patriotic upbringing.”

[pics_lr left="https://zn.ua/img/forall/u/667/61/GettyImages-472760114.jpg" ltitle="" right="https://zn.ua/img/forall/u/667/61/GettyImages-536245652.jpg" rtitle=""]

The same logic applies to doctors. In newly occupied areas, their pay is higher, but ordinary civilians feel little improvement, since many hospitals function primarily as military hospitals.

Police officers, on the other hand, are paid substantially more—up to 140,000 rubles (about 70,000 hryvnias, or $1,675). But only those who pass a loyalty screening qualify. In the first year of occupation, those who agreed to serve the Russians worked without uniforms, weapons or even official badges, with only paper certificates.

Later, they were sent on several months of “temporary duty” at the front, embedded with Russian army units.

Only afterward were they officially inducted into the Russian police, given proper gear and rewarded with enormous salaries by local standards.

Some of these Ukrainian policemen had first endured Russian prisons and torture chambers, only to be later released and forced into service, likely due to a lack of personnel.

According to Ukraine’s Defence Intelligence, at the few surviving industrial plants, wages range from 40,000 to 80,000 rubles (20–40,000 hryvnias, or $480–960). In small and medium private businesses, the pay is from 24,000 to 48,000 rubles (12–24,000 hryvnias, or $285–575).

Unexpectedly, one of the most well-off groups today are pensioners. After formally annexing the occupied territories, Russia began indexing pensions under its federal standards, though in a curious way. The documents of local pensioners were distributed across the entire Russian Federation, and they later received notices assigning them to distant offices—in Ufa, Perm and other cities. Perhaps this administrative scattering was meant to conceal the true number of beneficiaries dependent on Russian social aid.

Average pensions now reach 20–24,000 rubles (10–12,000 hryvnias, or $240–285), a high income by local standards.

With one hand, Russia distributes higher wages to certain categories of the population; with the other, it cancels out this arithmetic rise in income through higher prices. On local social networks, people constantly compare their earnings and expenses with those in Russia, usually with the neighboring border regions: the Rostov and Belgorod oblasts, and Krasnodar Krai.

The comparison is not in favor of the quasi-republics. Salaries and pensions have indeed been leveled with the Russian average—but only in the “newly” occupied territories.

In contrast, the prices of most basic foodstuffs are 15–25 percent higher than in Russia, while meat, fish and sausages are practically luxuries, costing 50–60 percent more. Such a price gap has existed since 2014, because at the Russian border, commercial cargo destined for Donetsk and Luhansk was subject to customs duties and treated as exports beyond Russia’s borders. The formal declaration of these regions’ annexation and their inclusion into the Russian Federation did not bring any price relief. Even though Moscow now officially considers the former state border an internal administrative boundary, prices have not gone down.

Among private entrepreneurs, the best earnings go to repair and construction crews—for the simple reason that there are very few of them left. Amid a water supply crisis, the short-term rental business has all but died, while hotels are overcrowded with travelers—mostly officials and officers—who have managed to install pumps and water tanks.

The transport sector is visibly in decline. Old, rusting buses and trams still run on routes but less and less frequently. Even in the “capitals” of the occupied regions, people now have to wait at stops for half an hour or more. For comparison: in 2012, when Donetsk was preparing to host the European Football Championship, the city authorities decided that on central routes the waiting time should not exceed five minutes and purchased the necessary number of buses and trams.

All this, of course, does nothing to revive the labor market. Nor does the absence of investment in infrastructure, which is steadily deteriorating through neglect.

According to residents of the occupied territories interviewed by ZN.UA, the Russian occupation authorities focus their attention only on those settlements that matter to their military contingent—that is, those located along the railway line running along the Azov Sea coast, linking Russian territory with Crimea by land. These are Mariupol and Volnovakha in the Donetsk region, Berdiansk in the neighboring Zaporizhzhia region and Skadovsk in the Kherson region. Luhansk, too, has not been overlooked: as an important logistics hub for the Russian army, it has for the first time ceased to play the role of Donetsk’s “junior brother” when it comes to capital investment.

It is hardly surprising, then, that under such conditions people have begun to leave. Ukraine’s Defence Intelligence estimates labor migration between 2014 and 2025 at around 900,000 people. In addition to unemployment and poverty, local men are also fleeing to avoid mobilization—which has not stopped in CADLR since 2022 and continues to this day.

Paradoxically, however, real estate prices have risen sharply. This was a reaction to decrees by the occupation authorities ordering the forcible confiscation of housing from certain categories of owners. Those blacklisted include not only alleged “Ukrainian spies” and other “traitors to the motherland” but also anyone who failed—or simply neglected—to re-register ownership of their apartments and houses under Russian law.

Fearing they might lose their homes for nothing, CADLR residents are trying to make the most of this last opportunity to sell and are actively seeking anyone who still has money to buy.

There are few such people left—except, perhaps, the military.

(No) Brother Should Go to War Against Brother

In early February 2022, the occupation authorities of CADLR announced unscheduled military training for conscripts.

One participant, a university student from Donetsk, later shared his impressions with peers living in government-controlled territories of Ukraine:

“It was nonsense! They took us to a field, handed us a Kalashnikov rifle, and that was it. We did nothing there. Sat around for two days, then they brought everyone back.”

He was cheerful, as were his friends. They all thought there would definitely be no war. “Who prepares for war like that?” they laughed.

Then CADLR saw the beginning of forced mobilization. According to Ukraine’s Defence Intelligence, in the territories occupied before 2022, the Russian army has conscripted by force around 100,000 people, in addition to those who voluntarily joined the occupiers back in 2014. The rest began frantically taking Russian citizenship and fleeing to the Russian Federation.

Donbas recruits were organized into two army corps: the 1st Army Corps in Donetsk region and the 2nd Army Corps in Luhansk. Both were incorporated into Russia’s 8th Combined Arms Army of the Southern Military District. The remaining men were assigned to individual regiments or attached to other Russian army units—and immediately thrown into battle in the invasion’s first wave.

As of today, according to various estimates, irrecoverable losses in these formations amount to roughly 40,000 people—killed, missing or gravely wounded.

For a long time, local conscripts were treated as inferior to troops from Russia. The lavish payments that Russian recruiters used to lure volunteers into military service did not apply to local fighters. Nor did compensation for serious injury or death.

After Moscow declared CADLR “part” of Russia, pay for soldiers in the 1st and 2nd Army Corps was gradually equalized with that of regular troops. According to Ukraine’s Defence Intelligence, Base salaries now range between 20,000 and 56,000 rubles—10–28,000 hryvnias, or roughly $250 to $700—and with combat bonuses their total earnings can reach 100,000–384,000 rubles (50–192,000 hryvnias, or $1,250–$4,800).

Locaks conscripted in CADLR have thus become virtually the only driver of the regional economy. Hotels and restaurants operate for their sake; the most expensive prostitutes come to them on call. Their friends and neighbors try to sell them their apartments before the occupation administration takes the property away without a penny in return.

They spend money as if it were the last day of their lives—and in many cases, it is.

But they also bring many problems.

Once, in Yenakiieve, Donetsk region, a grandson serving in the Russian army came to visit his grandparents. During a family gathering, after a few drinks, the men began to talk politics.

The old man allowed himself to say honestly that life had been better under Ukraine, and now everything had turned to ruin.

The conversation ended in a beating. Drunk and riled up by his grandfather’s seditious talk, the self-styled “liberator” beat him so severely that the old man ended up in intensive care.

The mass forced mobilization, coupled with an atmosphere of fear and repression, has given rise to a chilling local custom.

When residents of CADLR speak of relatives who never returned from the war, they suddenly fall silent.

“Mykolaivna, what about your grandson—the one who went to fight?”

“He’s gone.”

And at that, the conversation ends abruptly. Everyone averts their eyes. No one asks how he died, why, or—most importantly—what for.

The fear of saying a single wrong word forces people to keep their mouths shut.

The Women’s People’s Republic

Residents of the occupied Donetsk and Luhansk regions sometimes refer to their home, half in jest and half in bitterness, as the “ZhNR”—the Women’s People’s Republic.

The name was given for a reason: the effects of the refugee waves of 2014 and 2022, the forced mobilization and the flight of labor migrants are now unmistakable.

According to the Defence Intelligence of Ukraine, women make up at least 60 percent of the local population.

And they are not young girls. The proportion of elderly people keeps rising and has already exceeded 35 percent. Donbas is gradually taking on the features typical of regions scarred by prolonged war. Here, as in the Balkans, the dominant social group is retired older women. The young, given any chance, leave these war-scorched places, while the older remain, bound to their homes by nostalgia and illness.

The occupied territories are rapidly emptying out.

Compared with 2012, the population has more than halved.

Here are some numbers from Ukraine’s Defence Intelligence:

Predictably, in such conditions, the few young women who remain are in no hurry to have children.

Birth statistics now look like this:

Against this backdrop, the relatively stable population numbers in the regional centers appear somewhat unexpected.

Donetsk population (thousands):

2014 — 950

2022 — 900

2025 — 800

Luhansk population (thousands):

2014 — 463

2022 — 400

2025 — 300

In fact, there is nothing surprising about it if one remembers the region’s history. During both the Holodomor and the initial phase of the occupation in 2014, the same thing happened: people fled villages and small towns for the larger cities in search of work and safety.

Moreover, stability in the figures does not mean stability in the makeup of the population. Migration from Russia has not yet reached large numbers, but it continues steadily. Russians are not moving to the derelict or war-ravaged settlements under their own occupation; they are heading for the bigger cities—“comfortable” ones, by their standards. And compared with Russia’s own provincial backwaters, where the “Russian world” has ruled for centuries, even today’s impoverished Donetsk and Luhansk seem a better place to live.

The lottery of repressions

To call the situation in CADLR lawlessness would be inaccurate. Laws can only be broken where they exist.

Here, there is complete legal nihilism. In difficult situations, it never occurs to anyone to recall the existence of laws or those meant to uphold them.

Two neighbors quarrel over a domestic dispute and threaten each other:

“Just you wait! When my son comes back from the war, you’ll see! He’s been fighting for a long time, and he’s armed!”

“Mine’s been fighting since 2014—and he’s even crazier!”

A scuffle, a shouting match.

Frightened neighbors call the district policeman. He listens carefully and says:

“Ladies, please don’t drag me into a conflict between two armed men.”

Then turns around and leaves.

In this atmosphere of legal nihilism, security agents of every kind swarm like piranhas in muddy water, hunting for “Ukrainian spies.”

The exact number of civilians detained in CADLR is unknown. Sources put it at around 650 civilians persecuted as “Ukrainian spies,” though even they admit the figure is uncertain.

But a few hundred cases are more than enough to poison the air across CADLR with all-pervasive fear. Everyone knows it could happen to them—and that there is no one to turn to for protection.

Betrayal, on the other hand, is entirely predictable—even from those closest to you. Soviet behavioral patterns have resurfaced with startling ease in the new century.

People inform against one another. Everyone denounces everyone—friends, neighbors, classmates, relatives. They settle scores, save themselves at the cost of another’s freedom and build careers.

Anyone could turn out to be a snitch. The atmosphere of total mistrust resurrects the nightmares long thought buried— nightmares of prison for a joke told in the wrong company.

As in Stalin’s Great Purge of 1937–1938, the conveyor belt of repression chooses its victims arbitrarily. It doesn’t matter who you are or were, whether you truly oppose the regime or simply got in someone’s way. If there is a person, a charge will be found.

In lieu of an epilogue

Life in such conditions gradually mutilates the soul. It corrodes humanity, squeezes out dignity, makes the unacceptable ordinary.

One Donetsk resident was lucky. In an economically depressed city, he managed to earn enough to dream of building a small country home—not even far from the city center. His family gathered to discuss the details of the plan. The question arose whether to dig a well near the house. There seemed to be no mines nearby; perhaps they could secure their own water supply.

Different arguments were voiced, until the head of the family offered one that silenced everyone:

“Better not. The neighbors will shit in it right away.”

No one argued.

They will. They surely will.

Hatred toward anyone who tries, even slightly, to improve their inhuman living conditions has quietly become the new norm.

In the evenings, people in the occupied territories sometimes gather to talk.

About what?

About Ukraine. Still about Ukraine.

Most speak with hatred. They blame a country that has had no influence over their lives for more than ten years for all their misfortunes.

Some speak with sympathy. The older ones recall the times when they could go twice a week to Donbas Arena to watch football, not to line up for water trucks with plastic jugs. The young dream of escaping to that place, where one can travel freely across Europe without visas, study and build start-ups.

And perhaps, somewhere across the front line, someone is thinking of them too—one of those refugees who once walked these same streets and now treads the cobblestones of Lviv, the asphalt of Kyiv or the native mud of Donbas in combat boots as part of the Ukrainian Armed Forces.